Finding the heart of Philadelphia by exploring around its edges

When photographer J.J. Tiziou describes his recent project of walking the perimeter of Philadelphia in under a week, it sounds like he’s talking about life itself. But then that’s how conversations with Tiziou usually go.

“I’m glad we didn’t know what we were getting into, but we did it anyway.”

When photographer J.J. Tiziou describes his recent project of walking the perimeter of Philadelphia in under a week, it sounds like he’s talking about life itself. But then that’s how conversations with Tiziou usually go.

And as in life, he wasn’t alone. With a Knight Foundation grant, Tiziou paired up with writer Ann DeForest and two friends from Swim Pony, a performing arts group that hosted the project, to explore interdisciplinary art in a one-week timeframe. They came up with tons of ideas but then settled on what was right in front of them: the groundwork of Philadelphia. Literally.

The city at our feet

They decided to walk the entire perimeter of Philadelphia — about 103 miles — in five legs: 61st and Baltimore to Miquon; Miquon to Fox Chase; Fox Chase to Tacony; Tacony to the airport; and the airport to 61st and Baltimore.

Just for perspective, they bookended with stops at One Liberty Observation Deck. The journey, Tiziou says, changed the view. “Before we walked it, we looked all around, and we could only imagine what the walk would be,” he remembers. “The view on high afterward was so transformed after we’d gotten dirty and labored to go through it instead of just look down on it.”

Tiziou and team began and ended the labor at 61st and Baltimore. “Since we went clockwise, always to our right was Philadelphia and to our left was not-Philadelphia,” he says. “So we played the game of ‘Philadelphia-not-Philadelphia.’ In some places, the border was obvious — like a creek. And some places it wasn’t obvious, just like someone had drawn a line on a map.”

It made for a very revealing exercise in how we view the city, usually branded by the cluster of its tallest buildings. But the trip brought home how the city is really defined not by its highest buildings but by its real borders. “We’d round a corner, see the skyline, and say, ‘Oh, there’s Philly,” he says. “Then we’d catch ourselves and say, ‘No, this at my feet is the city.'”

Beyond urban experience

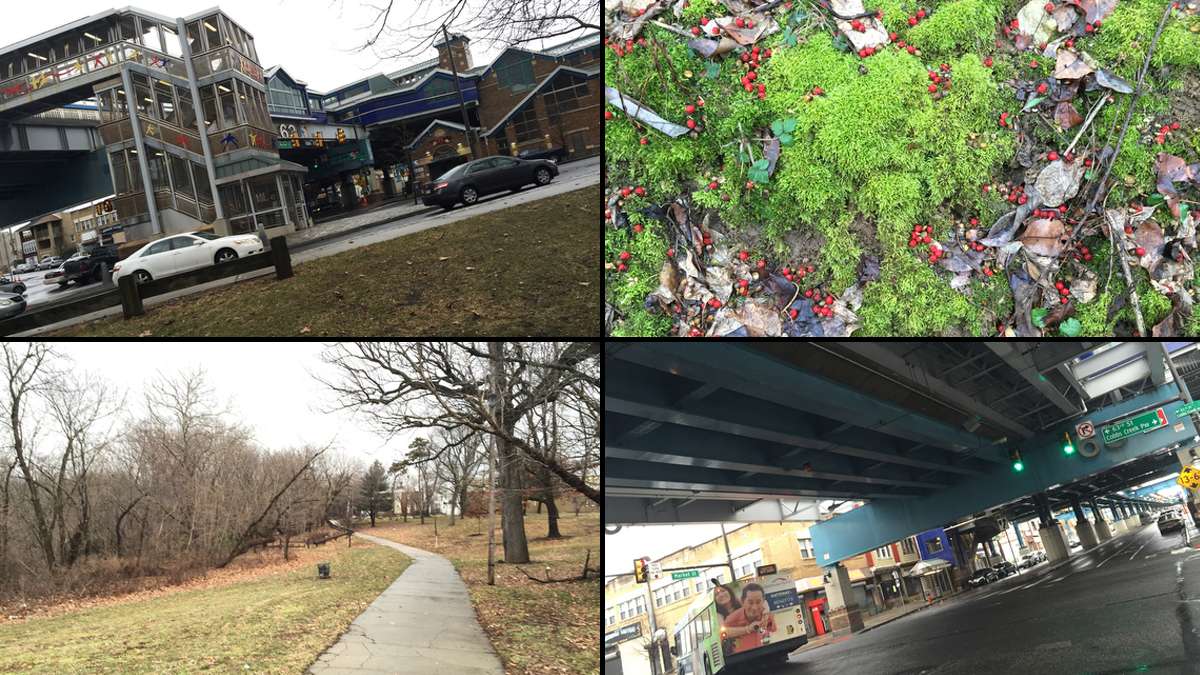

It might seem, instead, like it would have been a neighborhood experience — but there lay another surprise. “We set off with a rough idea of urban exploration,” Tiziou says. “But it wasn’t mostly urban. It was mostly industrial or rural. We were on the borders, where there’s a lot of water, industrial zones, a lot of woods and nature.”

As is usually the case for Tiziou, the physical experience became a spiritual one. “Because we had set out with the aim of the journey, we didn’t know exactly how we’d get to the destination,” he says. “We plotted our course, but we knew there would be places where we’d figure it out on the fly. The map doesn’t show you the details like the brambles or the fence. And of course the map doesn’t include the weather, which might include ice and rain.”

But as in the context of seeing all the details he and the others stumbled onto as part of the journey, Tiziou found that it was easier to welcome even the challenges. “The great thing was that since all of it was part of the journey, we enjoyed it. We laughed and smiled in the rain and in the wind. We enjoyed the sunny day as well. Things that could be downers like thorns or trash or windy cold weather, all of it was interesting. All of it was part of this rich experience.”

It’s a mindset we should bring to the journey of life, he adds. “Can you just be curious when it ‘rains’ or when you come across trash and brambles along the way?” Tiziou says. “What does it mean to approach things not with judgments but with curiosity and desire to learn?”

A reminder of privilege

There was yet another piece that lingered for Tiziou: the question of privilege. Anyone should be able to walk around in public spaces as they did, but the reality, he says, is that not just anyone can — either financially or in terms of welcome.

“A group of white folks with foundation money being paid to spend a week doing an art project — not everyone can afford to do that,” he says. “And more than that, some of the places we were received, like access to bathrooms, or accidentally crossing a golf course — would everyone be received in the same way?”

It hit home for Tiziou in an especially personal way. As he traced his way from South Philly up toward Northeast State Road where prisons are, he couldn’t help but parallel it with that of a friend who’d arrived there too — only from a disadvantaged background that led to time inside the prison. “We’re the exact same age,” Tiziou says of his friend. “Only he did it through the prison pipeline. I’ve had so many opportunities that led me to this particular journey. He’s had the opposite — lack of opportunities, lack of mentors and funding, and he had all the obstacles that led his journey into the prison system. Two precious babies were born 37 years ago — one to a middle-class, educated white family, and one in more poor circumstances in South Philly.”

In fact, the contrast provokes Tiziou to want to raise funds to scale up the experience for a broader audience that can transcend social, economic, and racial lines. “What if we gave the same money we had to people of different backgrounds, people from all sorts of neighborhoods to get to know each other along the journey,” he says. “It’s my fantasy plan, to pay other Philadelphians to do what we just did.”

Beyond making that fantasy into a reality, how do all those footsteps affect Tizou’s next life steps?

“I’m trying to walk more,” he says, “but not just to generate stuff. The last day I handed off my cell phone to my other walkers and said they were in charge of pictures, that I was just going to walk. And that opened up a different way of being. Even [earlier] when I wasn’t carrying lots of gear and only my cell phone, I saw how easy it had been to fall into the documenting mode. On the fifth day, I took time to experience more. Like, can we just sit on these benches and stare at the trees and grass. And those moments were pure magic, in a different type of magic than the type of magic I try to capture when I photograph. The deeper stillness.”

The biggest takeaway? “How powerful it is just to walk,” he says. “It made me want to get rid of all my stuff and become a pilgrim for the rest of my life.”

I support Tiziou but I’m hoping he holds onto his camera for awhile.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.