Finding beauty inside rules, the sonnet makes a small comeback

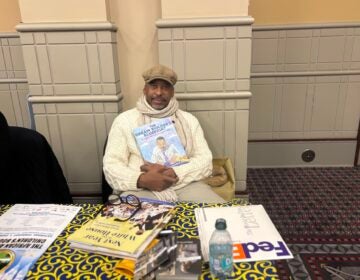

Philadelphia poet Ernest Hilbert's first books of poems, Sixty Sonnets (2009), it exactly what its title suggests. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

Next year, 2014, marks the 450th anniversary of the birth of William Shakespeare. Among the myriad events to mark the occasion is a sonnet-writing contest by the Philadelphia Shakespeare Theater.

The theater company is inviting four age groups — elementary, high school, college, and adult — to submit their best Elizabethan love sonnets. The winners will have the pleasure of hearing some of Shakespeare’s lines replaced by their own in a production of “Romeo and Juliet” this spring.

An Elizabethan sonnet is a form as cinched as a corset: It must have 14 lines, be in iambic pentameter, and its stanzas must hold to a rhyme scheme of a-b-a-b, then c-d-c-d, then e-f-e-f, finally using a rhyming couplet to sum up the emotion – which is, more often than not, love.

“I guess I wouldn’t call it rigid,” said Carmen Kahn, executive director of Philadelphia Shakespeare Theatre. “When you approach a craft, you approach it with discipline and you approach it with the idea of learning something, and your brain becomes more complex as a result of it.”

The classic Elizabethan sonnet is rarely written anymore outside of school assignments. You would be hard pressed to find a contemporary poet who would compare thee to a summer’s day. But the basic sonnet form is far from forgotten and it gets attempted more often than you might think.

Ernest Hilbert is a Philadelphia poet who spent years writing free verse in the Allen Ginsberg vein, but his first books of poems, Sixty Sonnets (2009), is exactly what its title suggests. Earlier this year he published his second volume – also a set of 60 sonnets — called All Of You On The Good Earth.

Hilbert’s poems keeps to 14 lines, but their meter can slide out of iambic pentameter, and the rhyme schemes are often of their own invention. Few, if any are about love.

His poem “Cover to Cover” is about a curious kind of love between a writer and his books.

I don’t collect them. They just accumulate,Tower higher into shoddy columns,Climbing weirdly like crystal formationsOr pillars of coral. The thought of their weightCrushes, their coarse traffic of wars I’ve thumbsThrough, their long summers and snow. They weigh tons.They slide onto the stove, under the fridge,into the tub. They prop open windows,serve as coasters. They have traveled with meand slept beside me. They fashion a bridgeto vanished rooms, sorrows, and suns. Lord knowsWhy I haul them from city to city.I slip them together like bricks. They become a wall,My greed, my fears, everything, nothing at all.

Hilbert experiments with how many ways he can prod, twist, and kick at the sonnet to pull the form into the 21st century.

“It’s a form we see a lot of these days. I don’t see a lot that I like, to be honest,” said Hilbert. “I think some are too old-fashioned, something that happens when people write in an old form. They suddenly adopt an old-fashioned formality and diction and focus. They are very limited in thinking about what the poem can be about. That’s a hang-up even good poets can fall prey to.”

There are only so many ways you can dismantle the sonnet before you can’t call it a sonnet anymore, and finding that line without crossing it becomes a creative challenge.

Al Filreis, a professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania, director of the center for programs in contemporary writing at the University of Pennsylvania, cites the mid-century poet Tom Berrigan as an example of a modern approach to sonnets.

“He has a phrase in the first sonnet in his sequence of many, many sonnets: ‘upon this structured tomb,'” said Filreis, who directs Penn’s Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing. “Well, that’s downright Shakespearean. It’s a meta-poetic statement, he’s talking about the poem itself, as a ‘structured tomb.’ Am I, by writing a sonnet, caught and stuck? Can I break out of it? Can I do something new?”

For the Sonnet contest of the Philadelphia Shakespeate Theater, submissions must adhere to variations of boy-meets-girl, so that their lines can be slipped into the action of the star-crossed lovers.

After all, the sonnet is about fulfilling rules, not breaking them.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.