Exploring the artistic legacy of George A. ‘Frolic’ Weymouth

Perhaps best known for his legacy of philanthropic work, Weymouth was also an accomplished painter. A new exhibit at the Brandywine River Museum of Art looks at this legacy.

Perhaps best known for his legacy of philanthropic work, George A. “Frolic” Weymouth was also an accomplished painter. A new exhibit at the museum he helped found looks at his artistic legacy.

“Frolic,” as he was known to most, was very much a man of two worlds. In the public world he was the face of his philanthropic activities. In his private world, he spent over five decades making art. We visited the Brandywine River Museum of Art, which Frolic helped found for the first retrospective of his artistic works.

While many people close to Weymouth knew he was a painter, the volume of his work wasn’t as well known. “I don’t think that they realized the whole scope of his work,” said Thomas Padon, the James H. Duff Director of the Brandywine River Museum of Art.

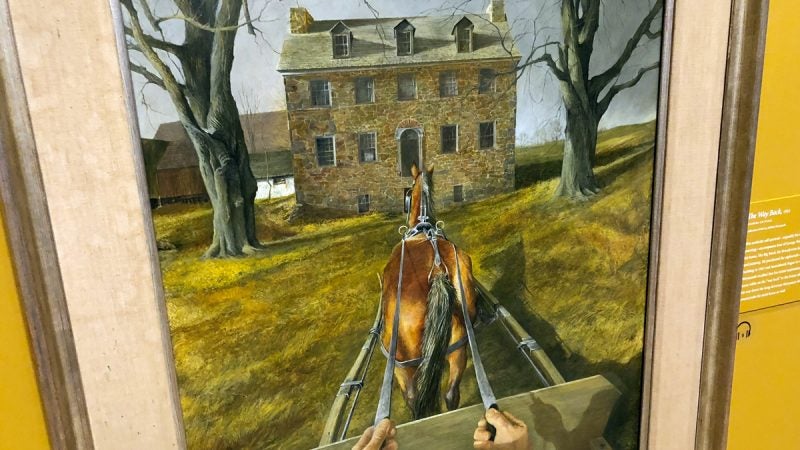

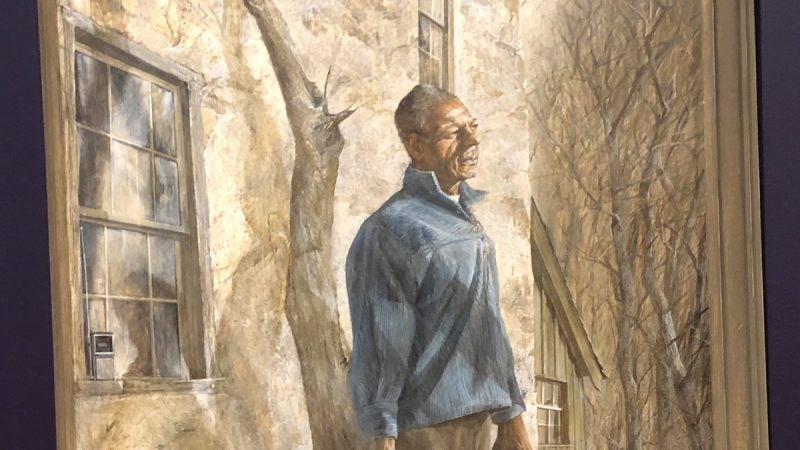

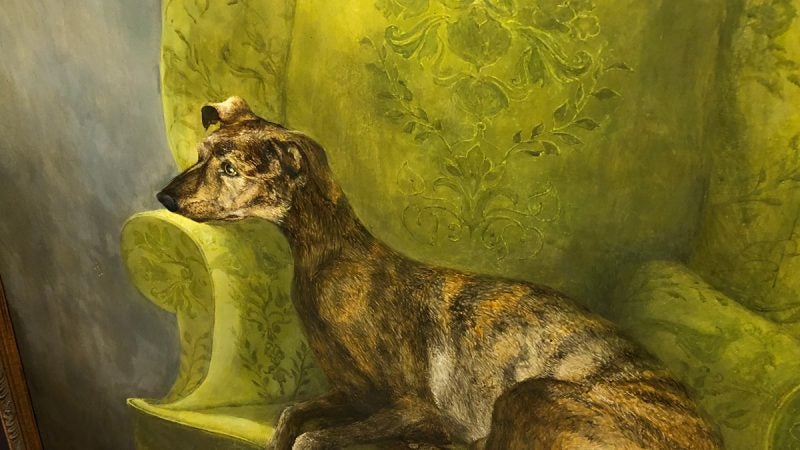

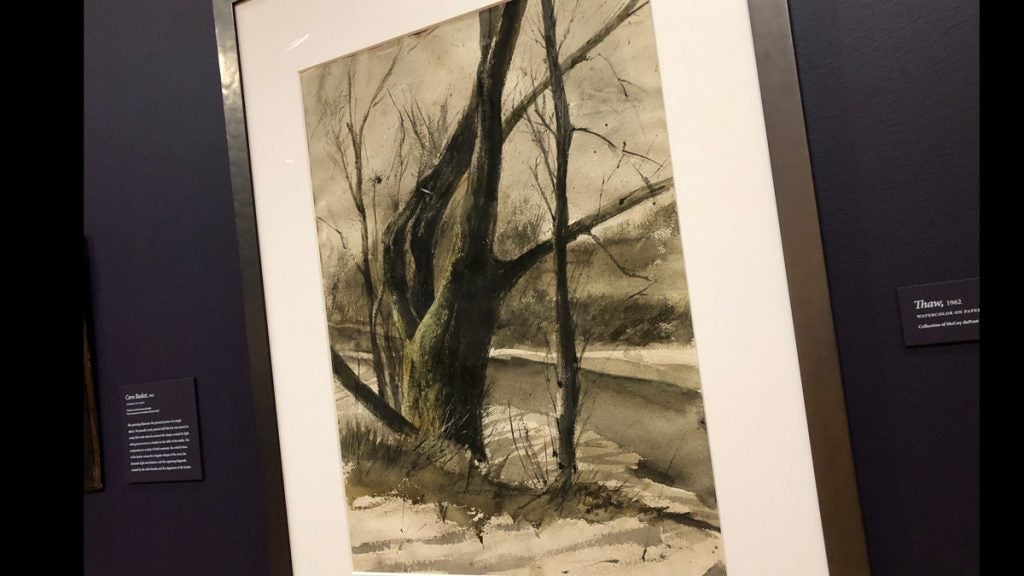

Weymouth was a very private painter, many of his paintings are of his home or the lands surrounding it or the people who lived or worked nearby. There’s an intimate quality you can see and feel as you view the work. “You’ll see in this exhibition there’s this very hushed quality, and it’s really the people and places that he knew,” Padon said.

One of those places Weymouth knew were the lands of the Brandywine Valley. Not only did he love to paint them, he also worked to help protect them through the Brandywine Conservancy.

Weymouth was one of the three founding members of the conservancy. “They really had the idea to save the cultural and natural resources of this area, and start an organization that would save the landscape and the artists work who have lived here,” Padon said.

The landscape seen in many of Weymouth’s paintings is protected by the Brandywine Conservancy, which now protects over 64,000 acres of land.

Weymouth’s own 250 acre estate, which he called the Big Bend is one such piece of land that is protected as well as featured in many of the paintings.

Friendship with Wyeth

One of Weymouth’s aunts introduced him to Andrew Wyeth. “Andrew Wyeth was very open, gave him feedback,” Padon said. After college Weymouth returned to Chadds Ford, and Weymouth and Wyeth became close friends. It was a friendship that lasted until Wyeth’s death in 2009.

As you look through the exhibit you may be mistaken in thinking you are looking at work by Wyeth. There is an unmistakable similarity in the visual style, and even the materials. That was not by accident.

Andrew Wyeth and his brother-in-law Peter Hurd once paid a visit to Weymouth. They suggested to Weymouth that he should try working in egg tempera painting to achieve the effect he was after. Egg tempera involves using finely ground dry pigments, egg yolk and water. Weymouth began using the technique and continued to use it for the rest of his life.

“I think that there is an unmistakable kind of visual reference in the work to Andrew Wyeth. That same kind of use of light, that very still quality, but I think Frolic really made the work his own,” Padon said.

Weymouth was a very important person to the Brandywine River Museum of Art. “We really wanted to put him in the context of American art,” Padon said.

The exhibit was in the works when Weymouth died in 2016. Being such a private painter how would he have felt having so many people view his work? “I think he would love the fact that people are here really looking at his work as works of art,” Padon said. Not just because of who this man was and what he meant to the area and those he touched through his philanthropy, but because of the art itself.

“I absolutely think he would love the fact that people are here looking at this,” Padon said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.