Exhibition traces a 200-year history of water pollution in Philadelphia

The Science History Institute opens “Downstream,” a historical exhibition of the science behind Delaware River watershed analysis.

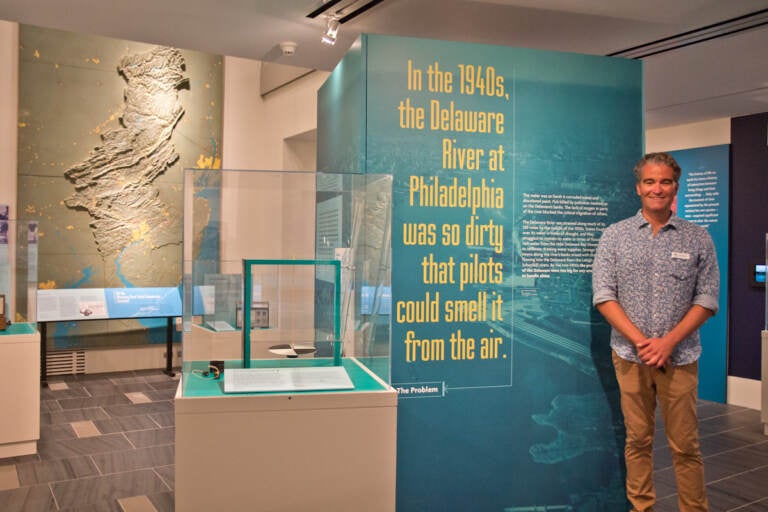

Jesse Smith, a research curator at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia, stands in the Downstream exhibit opening September 14, 2021. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

“Downstream,” the Science History Institute’s new exhibition about river water analysis over the last 200 years, explains the political and scientific history of watershed protection.

It opens Tuesday, Sept. 14, and answers the questions: What did we know, and when did we know it?

It starts at the birth of the United States, in the late 1700s when the capital of the new nation, Philadelphia, was a “wet and stinking mess,” according to the oversized text that immediately greets visitors upon entry.

The area around what is now Dock Street in Old City was dense with leather tanners and beer brewers, whose effluvia choked what was then Dock Creek with pollutants.

Curator Jesse Smith said people could see, smell, and taste the contaminants in the network of creeks that used to form a web of waterways throughout Philadelphia. Their human senses were their primary analytical tools.

“It was biological,” he said. “Waste from industries like tanning, like brewing, animals that were left to rot in waterways, and also vast amounts of human waste.”

Arranged chronologically, “Downstream” starts with the mess that was Center City water and follows the progressive development of water science over the next two centuries, and how it intersected with the ecology, politics, and economics of water.

Although people knew how bad the water was in the 1700s, nothing was done about it until people started dying en masse. A series of yellow fever epidemics — the most serious of which killed 10% of Philadelphia’s population, about 5,000 people, in the fall of 1793 — snapped the city into action.

Philadelphia needed a new source of clean water, and the Schuylkill River was the best candidate: a much cleaner waterway on the opposite side of the city from the heavily industrialized Delaware River.

The Fairmount Water Works was built as the nation’s first large-scale municipal water system, pulling drinking water from the Schuylkill and sending it through underground wooden pipes throughout the city.

To this day, the Philadelphia Water Department occasionally discovers original wooden pipes still underground. “Downstream” features a small section, about two feet long, under glass.

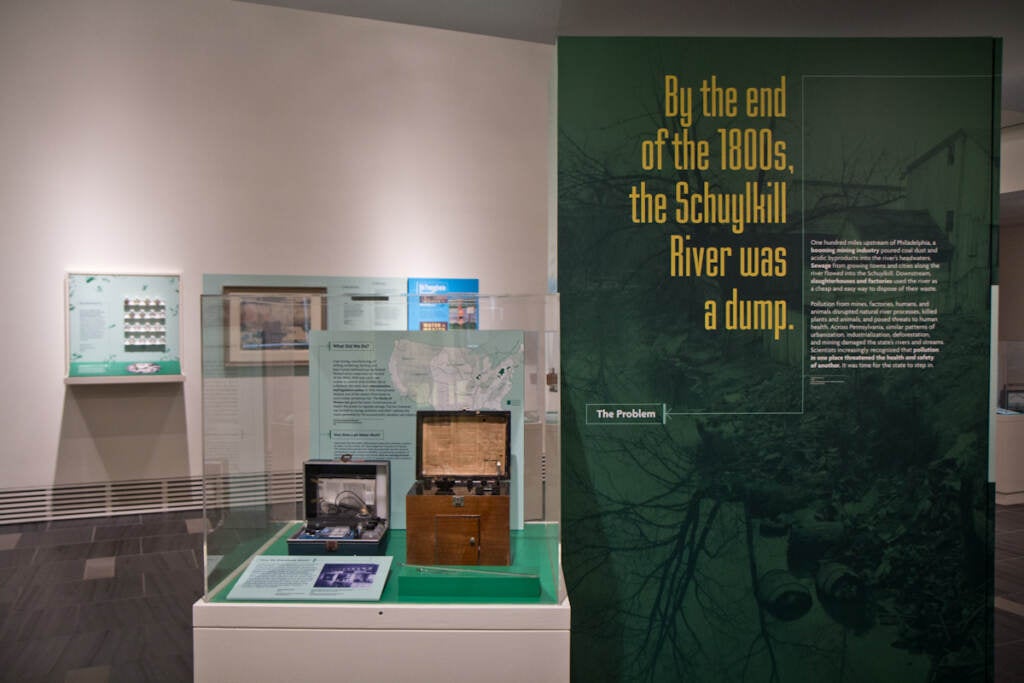

It did not take long for the Schuylkill River itself to become polluted from increased farming and industry upriver. People began to realize that clean water is not a local problem, but can originate far away.

“As upstream pollution was increasingly fouling Philadelphia’s source of drinking water, there were proposals to tap sources further upstream,” said Smith.

The exhibition features a historic map, about six feet long, showing a proposal to build an aqueduct that would pull water from roughly the area around Norristown and pipe it into Philadelphia, bypassing the sources of pollution. Another idea was to tap into the waters of the New Jersey Pine Barrens, whose sandy geography acts as a natural filtration system. Similar solutions were adopted in other cities, notably New York, which imports its water from upstate.

“Philadelphia’s decision ultimately was to treat the water that it had here,” said Smith.

In the era of the Industrial Revolution, pollution was no longer primarily biological: It didn’t necessarily smell bad. Newer chemicals and contaminants could not be detected simply by looking and sniffing.

By the late 1800s, people had to know exactly what was in the water.

Notable women of water analysis, and historical artifacts

Collecting scientific equipment is the Science History Institute’s stock in trade, and “Downstream” features many early 20th-century contraptions for analyzing water, from colorimeters of the 1920s that detect chemicals, a portable oxygen analyzer from the 1950s that measured the amount of oxygen present in water, and a prototype of a diatometer, a device that collects waterborne diatoms, a type of algae, that was developed by botanist Ruth Patrick of the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Patrick developed an eponymous scientific technique, the “Patrick Principle,” to measure the presence of simple organisms as a way to determine the type and degree of water pollution.

Next to Patrick’s crude diatometer — basically a series of glass slides bobbing in the water via cork floats — is an exhibit about another prominent woman in the history of watershed protection in Pennsylvania, Mira Lloyd Dock.

In some ways, Dock was the Al Gore of her day, traveling across the commonwealth in the late 19th century with a lantern slide show and explaining the importance of forests and watersheds to the health of Pennsylvania.

In 1901, Dock was appointed to Pennsylvania’s Forest Commission, the first woman in the world to serve on such a commission, and the first woman in Pennsylvania to be appointed to a job in state government. During her 12 years on the commission, it protected 1 million acres of forest as land reserves.

“Downstream” gets into the politics of river conservation, the lobbying by the coal industry to secure exceptions to regulations, and steps taken by state and federal governments to control waterways — including the creation in 1936 of the Interstate Commission on the Delaware River Basin between Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey; the federal government’s creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority in 1933; and the Missouri River Basin Project of 1944.

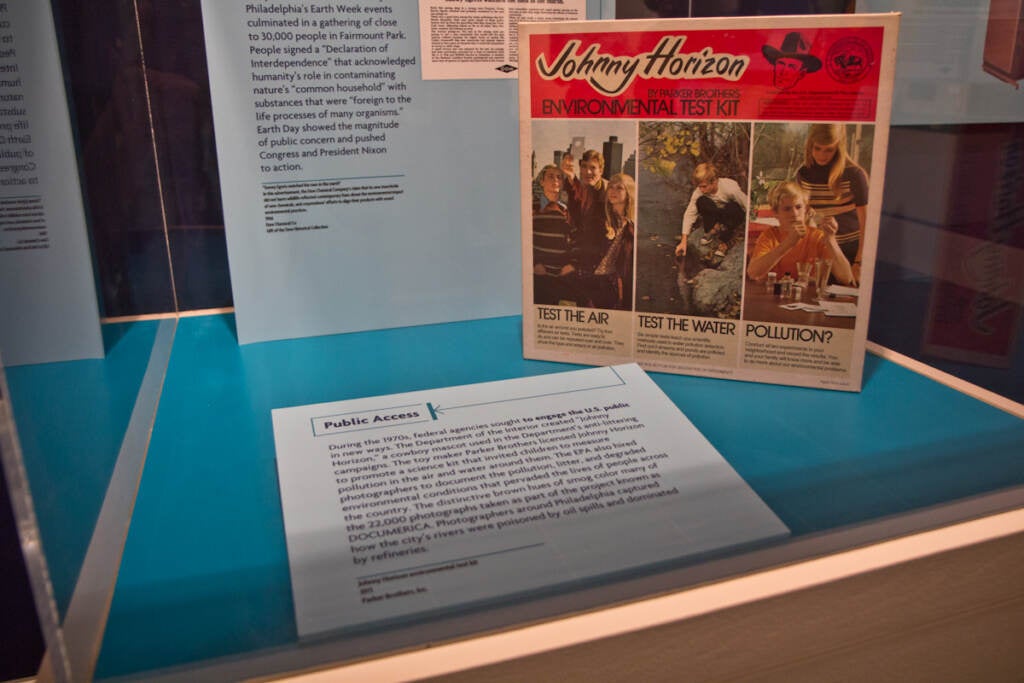

By the 1970s, with the passage of the Environmental Protection Act, popular interest in the science of water prompted Parker Bros. to create a pollution test kit for children. The “Downstream” exhibition features an original box of “Johnny Horizon’s Environmental Test Kit,” including 10 different ways to test air and water pollution, for kids aged 10 and up.

Later this month, the Science History Institute will erect outside its building large-scale reprints of posters from a 1960s public anti-pollution campaign by Pennsylvania’s Sanitary Water Board, “Water is Wealth.”

“One of the things that we were interested in are contemporary challenges to water quality,” said Smith. “One part of the exhibition explores the emergence of microplastics as a particular area of concern. We’re not quite sure exactly what impact microplastics will have on human and environmental health right now. So the ongoing challenge of keeping our water clean made it seem important to explore the historical relationships behind that protection.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.