Joe Beam’s memory and LGBT racism

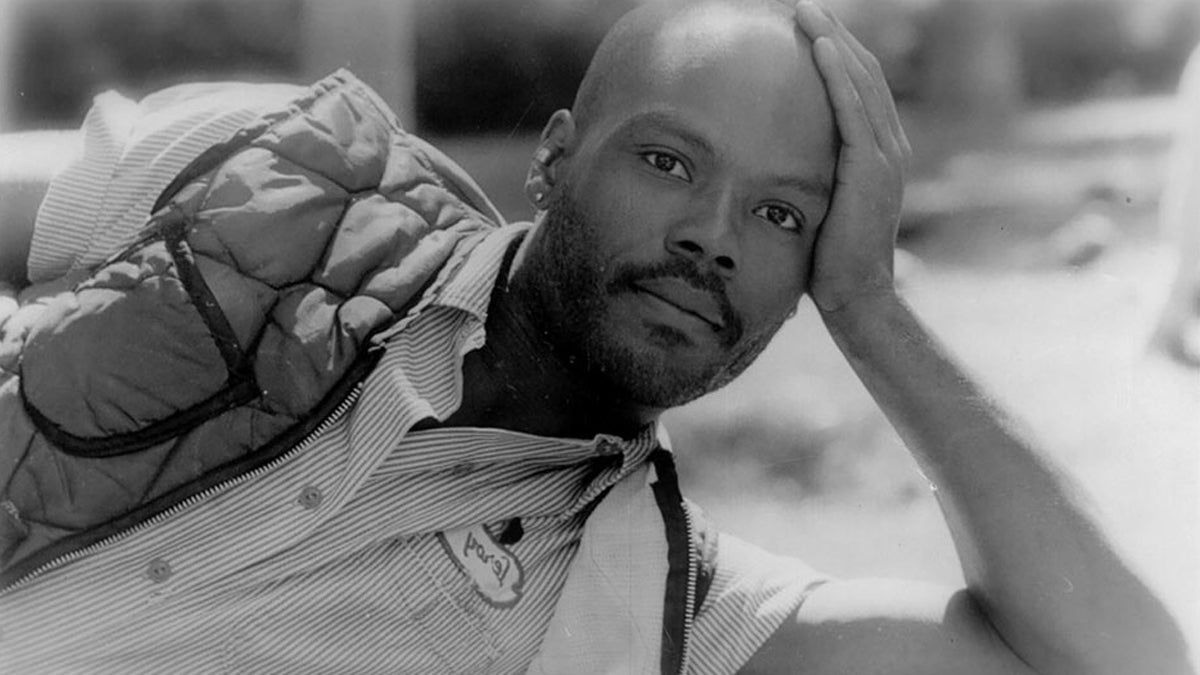

Joe Beam edited 'In the Life

It is ironic that the 30th anniversary of “In the Life,” the historic black gay male anthology that Joe Beam compiled and edited, occurs while the Philadelphia LGBT community is suddenly conscious of racism.

It is an ironic concurrence that the 30th anniversary of the publication of “In the Life,” the historic black gay male anthology that Joe Beam compiled and edited, occurs while the Philadelphia LGBT community is suddenly conscious of racism.

Joe and I were friends. I knew him from the LGBT bookstore Giovanni’s Room, where he worked, from social gatherings, and from just running into each other in Center City. He lived on 20th and Spruce, I lived at 15th and Delancey (now the loading dock of the Kimmel Center). Center City was more diverse then.

When I wrote about racism in Philadelphia restaurants in the ’80s, Joe told me about his difficulty finding work as a waiter. It was easy for white college graduates in the arts to wait tables but not for black college graduates in the arts.

Joe edited an article I wrote about the murders of transgender black women for Black/Out magazine. He wanted me to submit an essay for “In The Life,” but I thought it was inappropriate, as a transsexual woman, to write for a gay men’s anthology. I supported Joe by helping him proof the galleys. This is why I appear in the book’s acknowledgements.

Regarding the murder rate and the AIDS crisis and the attitude of some black gay men, Joe said: “If I’m going to die by a gun or die by a dick, I’ll die by a dick!” He wasn’t speaking about himself specifically but about a fatalist mentality.

During his all too brief life, Joe pioneered writing about the black gay male experience and activism in the 1980s. He argued with editors because he wanted Black, as in a racial designation, capitalized, the way Italian, Irish, Thai, etc. are.

He appeared often in Au Courant, Blackheart, Changing Men, Gay Community News, Philadelphia Gay News, The Advocate, New York Native, Body Politic, and Windy City Times, and he was the founding editor of Black/Out magazine. Joe interviewed Audre Lorde and collaborated with his friends Essex Hemphill and Marlon Riggs. He died of complications from AIDS a few days shy of his 34th birthday in 1988.

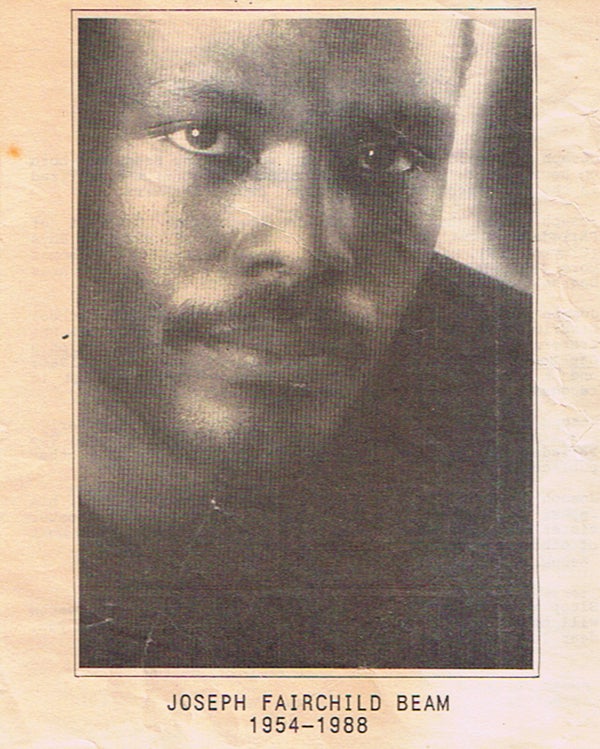

Scan of a program from Joseph Beam’s memorial service in 1988. (Courtesy of Cei Bell)

Scan of a program from Joseph Beam’s memorial service in 1988. (Courtesy of Cei Bell)

The recent surfacing of a 3-year-old video showing Darryl DePiano, the owner of Gayborhbood night spot iCandy, repeatedly using the N-word and slandering his black patrons may highlight racism in the Gayborhood, but it is nothing new.

When I worked at the DCA Club in the ’80s, where Voyeur is now, a big 6’5″ white manager would get drunk, use the N-word openly, and come up behind me and slap my rear with all his strength, essentially punching my rear in front of a crowded dance floor. Some white bartenders said it was horrible, but nobody did anything. He later went on to be the advertising manager at PGN and work at other gay businesses.

There is an even bigger problem with racism in LGBT organizations than there is in the bars. Most of the organizing in the LGBT community is around white professionals. While the acronym is LGBT, the axis is always gay white men. For more than a month, the recent columnists featured in PGN have all been white.

I wrote the workshop plans for the first (maybe only?) Conference on Racism and Sexism in Lesbian and Gay Institutions that convened at the Friends Center in 1981. One question I asked is to look around your environment at work, school, your neighborhood, your social environment and ask yourself why the racial demographic you see is the way it is. If the City is 40 to 50 percent Black, 10 to 15 percent other minorities, and the remaining white, then why would you be in a mostly white group?

In the ’70s I would see white people who I knew from Gay Activist Alliance and other organizations on the street and if I said hello they would walk past me as though we never met. I was stunned when Joe told me that happened to him with people he knew from Giovanni’s Room. This past winter a white board member of Liberty City Democratic Club passed me by on the street when I said hello. The board member knew I was co-chair of the Endorsement Committee at LCDC.

In 1976 I worked with the Bicentennial Coalition protest that held a march of progressive groups through Fairmount Park on the 4th of July. I organized the lesbian and gay contingent. I wrote about it, distributed leaflets, and appeared on WXPN. I was at the March at 6 a.m. to get water from neighbors and to marshal. After working all day with demonstrators, I went to a reception at the home of a Prominent Gay Man. The moment I walked in, he shoved me into the kitchen to cut up cheese. All around me were gay white men standing and drinking wine. None of them were cutting cheese. I hadn’t been offered wine. One of the men, referring to the forced sterilizations of women in Central America, said, “But what about the population explosion?” I stopped cutting cheese. I told the host I was leaving because I thought this was a racist situation. He had this big liberal hurt look on his face. He didn’t understand I was talking about him.

I have been involved with many so-called LGBT groups over the years that had trouble with diversity. These groups were not able to attract minorities or transgender people or both. There would be ongoing discussions about how to bring minorities and trans people into the organizations. I would often be the only black person or the only transgender person. As a result I would have to supply black or trans points of view, often both, and it was very tiring.

The famous Quaker peace activist George Lakey wrote about me in “No Turning Back: Lesbian and Gay Liberation for the ’80s.” He used the pseudonym G. Talbott for me and wrote about a period in the late ’70s when I stopped transitioning. He quoted me as saying, “I found out about androgyny, dear. And I know the world isn’t ready, but I’m willing to be first.” He also wrote: “We are guessing that because masculinity and femininity are more polarized in parts of the working class than in most of the middle/upper class, gay working-class boys are more often made to feel they must choose, and, given the choice, identify with women rather than men.”

The problem is we never had that conversation. At all. Lakey made the whole thing up. It didn’t even make logical sense. I co-founded Radical Queens, a group that dealt with issues of androgyny, in 1973. Why would I be discovering it in the late ’70s? We never discussed whether I was raised working class or middle class. My father was a Prince Hall Mason who owned rental properties and obtained mortgages, despite redlining. Lakey had no clue what my father’s issues were. I stopped transitioning because I had been raped twice, some men had tried to murder me, and I needed to take a step back at the time because I had no support.

If you want to know why the white LGB community is just now becoming aware that transgender women of color are being slaughtered, look at that book. It is because they didn’t care. Instead of using the book to shine a light on the issues of black transgender women, Lakey used me for his political motives. Years later he admitted he was uncomfortable about the subject. The authors wrote: “This writing reflects who we, the authors, are: urban and white. We are not able to write about the experience of gay men of color nor or urban gays who have their own unique experience.” They lived in Philadelphia where people of color are everywhere. Lakey lived in West Philadelphia. They could have found some black men. Joe Beam was active in Philadelphia at that time. There were black gay groups. The authors just couldn’t climb over their own barriers.

Unable to find lesbians of color for the the chapter “Lesbians of Color” the chapter was written by a white lesbian “for other white people.”

The cover of the book has a positive review from Larry Gross who was a professor of communications at Annenberg and who apparently didn’t notice the lack of people of color.

I once had an argument with a campaign manager about a fundraiser he was planning for an LGBT candidate for a citywide office. The lowest-price donation was for students and young professionals. A wealthy Penn student or a young professional with disposable income could pay the lower price. I told him that the fundraiser excluded working class people and a lot of people of color, both of whom comprise the majority of the city’s population, the very voters whose support he needed. He didn’t understand.

At the Liberty City Democratic Club welcome party for the 2016 Democratic National Convention, the partner of a prominent politically active gay man grabbed my breast. He would have never dared do that to a white lesbian.

I have been complaining for over a decade that there was no outreach to black transgender voters or even transgender voters in Pennsylvania. During the 2004 and 2008 presidential election a gay men would be appointed to do LGBT outreach, but he would do no outreach to T. In 2012 I organized The Real T-Party, a voter clinic for transgender people, but outreach to the trans community still suffers.

Last July, the Democratic Party wanted to show off its diversity with 27 transgender delegates at the national convention in Philadelphia. No black transgender people had been developed as delegate candidates for the primary. Instead, a black transgender woman was appointed to represent Pennsylvania. She was the only black transgender female delegate at the DNC. This is tokenism spinned as inspiration.

This also means that the rest of the country didn’t even try. Marisa J. Richmond, Ph.D., was the first transgender female delegate of color at the DNC in 2008. She was also a delegate at the 2012 DNC. Unfortunately she did not return as a delegate this year. Having only one or two transgender women of color as delegates for the entire country is disgraceful.

It is not the responsibility of LGBTQI people of color to provide the solution to racism for white people. Because of the new political climate there is more than enough work for us to do to protect ourselves. If white LGBTQI people and organizations seriously want to be inclusive then they have to do the work to be inclusive. If they can’t find people of color for their organizations perhaps they could start with their own lives and ask why they don’t have any friends who are people of color. With such a diverse city it shouldn’t be that difficult.

If Joe were here today I think he would be disappointed, but I doubt he would be surprised.

—

Cei Bell is a freelance writer living in Philadelphia. She is the recipient of the Leeway Foundation 2015 Transformation Award for Literature.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.