It takes a ‘learning hero’ to break out of the education pipeline

Who is your learning hero? Who would you say has been an inspirational person in your life who has unlocked new ideas and pushed you to learn?

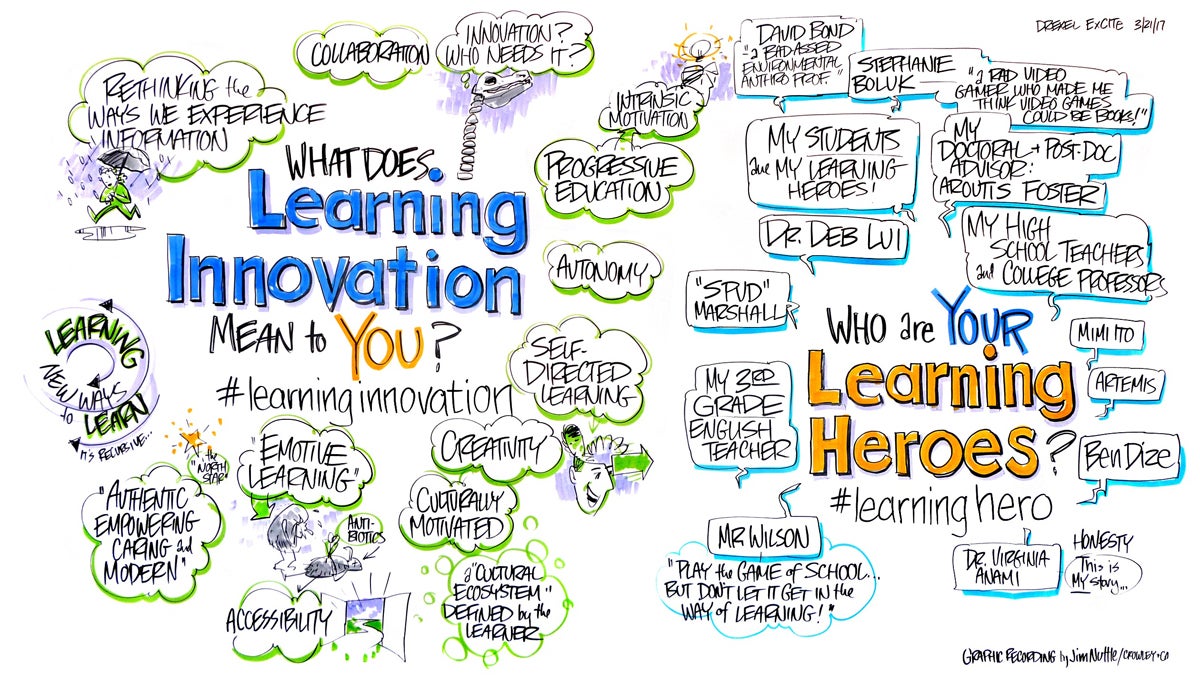

Artist Jim Nuttle captured Mimi Ito's Learning Innovation presentation.

Who is your learning hero? Who would you say has been an inspirational person in your life who has unlocked new ideas and pushed you to learn?

Cultural anthropologist Mizuko “Mimi” Ito asked that question when she spoke last month at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University about technology use, and how the ways in which kids’ relationship with media and communication is changing might lead to innovations in education. Her presentation was part of an ongoing project of Drexel’s ExCITe Center, called “Learning Innovation.”

Ito suggested that turning out productive, creative learners depends on getting outside of the traditional pipline that shuttles students from elementary school to high school to college and onto a career. Deep, engaged learning in vital fields like science, technology, engineering, and mathematics is often unlocked by building support networks that encourage innate interests. Learning heroes who help inspire those students can be coaches, hobbyists, mentors, parents, and teachers — even the guy at the aquarium shop who inspired her son to learn more about the life cycle of frogs.

Audience members tweeted that night about their #learninghero, and Ito encouraged them to send their stories to NewsWorks. Ito also reminded guests that they should make sure their heroes know the impact they had on them. Here are a few of those learning hero stories.

‘I am network effect’

From Andrea Forte, associate professor and director of the Ph.D. program in information studies in the College of Computing and Informatics at Drexel University:

i have no #learninghero because about 120 heroes were necessary to get me here. i am network effect. #learninginnovation

— andrea forte (@andicat) March 21, 2017

Do I credit my mom for teaching me programming and the example she set when she returned to college? Do I credit my dad for the chess lessons that taught me perseverance and learning from mistakes? The quirky high school biology teacher who made science fun? The many other teachers who treated me like a person with ideas that matter? The college professor who encouraged my writing by taking my essays seriously enough to assign one as required reading for future classes? The Ph.D. advisor who championed my work and opened doors I never even knew existed? How could I even begin to credit the many mentors who witnessed my weaknesses and failures as well as interests and abilities and helped set the conditions I needed to be a lifelong learner? 140 characters wouldn’t do it. … I realized that there was no hero, because none of these individuals could have given me a boost to where I am without the unseen hands of many others. So instead of a hero, I tweeted that I am network effect.

“Network effect” is a term that describes how something — usually a product or service — becomes more valuable as more people use it. I use this term metaphorically to describe the network of “heroes” who interacted with me over a lifetime to unlock my potential as a learner.

Today I am a professor, a scientist, a coder, an advisor, a teacher, a mom. Perhaps someday I will be counted as a learning hero in one of these roles, but I realize that, more importantly, I can work to help my students, colleagues, and children grow strong networks that enrich and add value to their lives and create conditions for future learning and success.

Escaping to a new world by building a better one

From Matthew Lee, self-described gamer, artist, scholar, nurse, and Fulbright Fellow in Psychology, who explores the role of serious games and focuses on developing a community for those working with and interested in serious games:

How can we use our organizations to be #learningheroes and connect with promising youth? #learninginnovation

— Matthew Lee (@AlfheimWanderer) March 21, 2017

As a kid, I dreamed of being an astronaut and touching the soil of a distant world. It made me a little different from other kids, and I was bullied quite a bit, making me fairly unhappy for much of my childhood. I looked up at the sky, longing to escape, to leave the slings and arrows of the playground behind and go … elsewhere.

Only there was nowhere to go.

School was school, home was home, and every day was just another day to get through. I didn’t really expect things to change when I went to high school, but they did.

During my first week, I caught a snatch of conversation about a space settlement design competition coming from a classroom after school. Curious, I poked my head in the door. The science club’s advisor, Phil Turek, invited me to join them.

Mr. Turek, physics teacher and expert cookie baker, was my first mentor. He took me along to conferences, where I met people like Bill Nye and Robert Picardo. He sponsored my participation in the international finals of the design competition I’d learned of my first week. And he always, always listened.

In my youth, I dreamed of escaping to a new world, somewhere I felt I belonged. Mr. Turek showed me that I could try creating a better one instead, using my talents to make change and build communities.

Today, as a game designer who works with serious play — and as chair of the IGDA Serious Games SIG, that lesson still resonates as powerfully as ever. Today, I don’t just build games — I change minds and touch hearts, working to improve society, one game (world) at a time.

A sequence of small victories and failures

From Betty Chandy, director of the virtual online teaching program at the Univeristy of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education:

#learninghero Husband

— Betty Chandy (@chandy_b) March 21, 2017

In college, I watched my boyfriend, now my husband, work his way through endless GRE practice tests to fulfill his dream of studying in the United States. Though I harbored similar ambitions, I knew I would never make it that far, given my high school trouble with math, and English as a second language. I would never achieve a respectable GRE score to have any graduate school consider my application seriously. My plans were much simpler: Finish college, and start teaching.

But in the months that followed after I got my first job, he got me to reconsider my life plans, and pushed me to go back to school. I opened my first Barron’s GRE prep guide one summer day in 2003 — and quit after 10 minutes. He encouraged me to try again, and mailed me study resources from the U.S. From there, to the day in Spring 2013 when I graduated from Penn with a doctorate degree in education, my story is an endless sequence of small victories and failures that made me who I am.

This was possible only because of the support, encouragement, patience, and love of my husband, for which I am eternally grateful!

The courage to be creative

From Alina Wheeler, author or “Designing Brand Identity“:

#learninghero Keith Yamashita

— Alina Wheeler (@alinawheeler) March 21, 2017

Keith Yamashita is my learning hero because he is powerful yet gentle, creative and strategic, and gives people the courage to change. His firm SYPartners tackles complex problems for some of the largest organizations in the world, and brings them through a process to define and attain their greatness. Unlike other business consultancies, SYPartners has no MBAs, and is made up of designers, technologists, storytellers, and sociologists. Keith gives me courage to use my creativity to design the future and to be inventive.

How to win at ‘the game of school’

From Chris Lehman, founding principal of the Science Leadership Academy, chair of Inquiry Schools, co-chair of EduCon, and author of “Building School 2.0: How to Create the Schools We Need”:

My #learninghero is Mr. Wilson – my 11th grade English teacher who taught me that I could play the game of school and learn deeply too.

— Chris Lehmann (@chrislehmann) March 21, 2017

When I was in 11th grade, I met Mr. Wilson. He was my English teacher, and he was the teacher sponsor of the Pennsbury TV Sports program. “Big Al” Wilson was the kind of teacher who always had a group of kids around him. His office was where we all hung out when we had a free period — and sometimes when we didn’t. We read Japanese detective fiction and Shakespeare and everything in between. We filmed basketball games and field hockey games and football games, and everything the school did. What we did in his class always felt vital and important, even if so much else in school didn’t.

But that was the thing Mr. Wilson gave me. I was 17 years old and questioning why I was working hard, why grades mattered, why school mattered. And Mr. Wilson was the teacher who said, “Yes … of course school is a game. But play it. Get the grades, because it’ll put you in the next room you want to be in. It’ll put you around tons of other really smart people who will push you to think and learn.”

He also said, “And don’t do well in school because your parents expect you to or because the school expects you to. Do this because it’s for you.”

At a time when I was questioning the apparatus of school and school success, Mr. Wilson was the teacher who reframed it for me and helped me see my way through school. He also was the first teacher who helped me see school for what it was, and that transparency was part of what allowed me to think differently about school years later when the time came for me to start my own.

Thanks, Mr. Wilson.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.