I found joy and wholeness in ’90s queer rock of ‘Hedwig & the Angry Inch’

I'd graduated from high school in a small town two hours north of New York City, and had decided that musical theater was my passion. It wasn't.

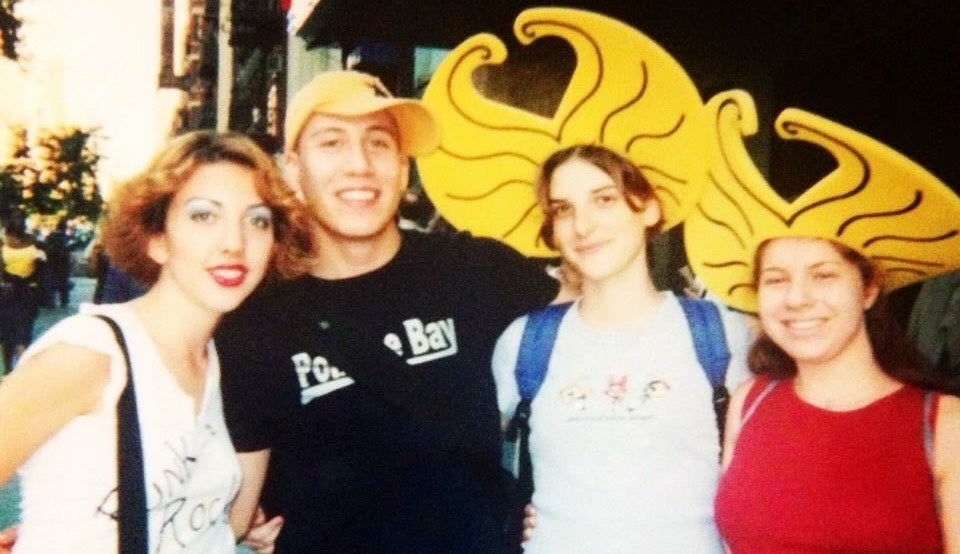

The author is shown, second from left, at the premiere of the 2001 film version of 'Hedwig and the Angry Inch.' (Image courtesy of Alejandro Morales)

Through the month of June, we are asking LGBTQ readers to submit essays about experiences in their lives that have brought them pride, happiness, and triumph. Email speakeasy@whyy.org to contribute.

—

It is the late ’90s. I am in my early late teens, with a head of dyed-blue curly hair and silvery glitter freckles on both cheeks. The New York City subway’s red line deposits me at 14th Street, and I walk westward on Jane Street, toward the river, along a rainbow trail of gummy bears outlined on the sidewalk in spray paint. At the end of the rainbow, my destination: the Jane Street Theatre. I’m here to volunteer, once again, as an usher for the off-Broadway run of “Hedwig & the Angry Inch.”

Before Sundance, before Broadway, there was The Jane. And me, a pimply musical theater major handing out programs and guiding patrons to their seats in the modest, threadbare performance space.

Ushering the show meant I could see the show for free, sometimes in the front row, close enough to see the sweat on the beer bottles that the evening’s Hedwig would drink from a pink straw between numbers. John Cameron Mitchell, Michael Cerveris, Matt McGrath, Kevin Cahoon, Donovan Leitch, Ally Sheedy; I saw them all, snarling with bitterness, cracking wise, singing their hearts out. Each time was as magical as the first.

I was mesmerized by the fearless presence of Hedwig, by her power to transform herself and those around her — and her journey to wholeness has kept me company ever since.

The nights I spent watching the passion of the ‘wig were the highlight of a year that otherwise didn’t go so great for me. I’d graduated from high school in Ellenville, New York, a small town two hours north of New York City, and had decided that musical theater was my passion.

It wasn’t.

I couldn’t have named more than 10 musicals at the time with a gun to my head. But the theater department and the music room of my school were the only places I felt like myself, and I loved to sing and ham it up. For me, and for a lot of young dreamers out in the sticks, NYC was that land of milk and honey, where a grungy little gay nerd could find his own tribe, free from alienation and the homophobic epithets whispered in hallways and classrooms.

And sure, New York delivered the goods in many ways. Nobody called me a faggot, so that was pretty cool. But I didn’t have a strong character. I was too eager to discard my old self, to be whoever would fit in with the kids at my musical theater conservatory, and I fell in with a group of hard partiers and drag queens. I started classes in October. By November I was doing ecstasy and waving glowsticks around in ladybug wings and raver pants. And by March of 2000, I had dropped out and moved back home.

Along the way, though, there was Hedwig. I saw my own vulnerability and resolve in her, I saw my own efforts to make myself over in her thrift store glam attire and self-deprecating barbs. In the later Broadway staging of the show, Hedwig stomps across the elaborate joke-set of “Hurt Locker: The Musical.” But in the off-Broadway days, Hedwig’s story literally took place in the Jane Street Theater, which according to lore had once sheltered the surviving crew of the Titanic.

“Perhaps they can hear me now,” Hedwig would muse, gesturing to the balconies, bottle in hand, “You brave unfortunate souls — blasted by man’s hubris and washed up on cruel shores — I, who am simply blasted and washed up, salute you.”

The story spoke to me. Hedwig was an “internationally ignored” songstress, staging a rickety cabaret in a flophouse by the river, as her more-successful protege and former lover Tommy Gnosis headlined a mega-concert nearby. Throughout the show, she grappled with her demons and tried to make sense of the past, wondering aloud if there was a soulmate, or other half, that would make her whole.

I had questions about wholeness, too, and while I couldn’t possibly have appreciated then just where the life of an artist would take me, I did know about feeling chewed up and spit out. I was having a hard time, and Hedwig was having a hard time, too.

But she still told her story, and she still sang her songs, and like a Phoenix in red lipstick and acid-wash denim, she rose from the ashes, proclaiming “Know in your soul, like your blood knows the way, from your heart to your brain, know that you’re whole.” After all she’d been through, Hedwig, singing the final song of the show, had transcended her circumstances and found fulfillment in the moment, making it her moment. And awash in that splendor, in the finale chorus of the show, Hedwig would stretch a hand towards the ceiling and command the audience: “Lift up your hands! Lift up your hands! Lift up your hands!” And in those days, in that small theater, every single person’s arms would shoot up straight into the sky, swaying and stretching, and mine would too, and in those moments I felt the purest joy of my queer life, because I felt whole, too.

—

Alejandro Morales is a stand-up comedian and screenwriter in Philadelphia.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.