I didn’t understand the Vietnam War until I met my father-in-law

I could never truly understand the Vietnam War. It was too far away from my memorable history — until I married my wife.

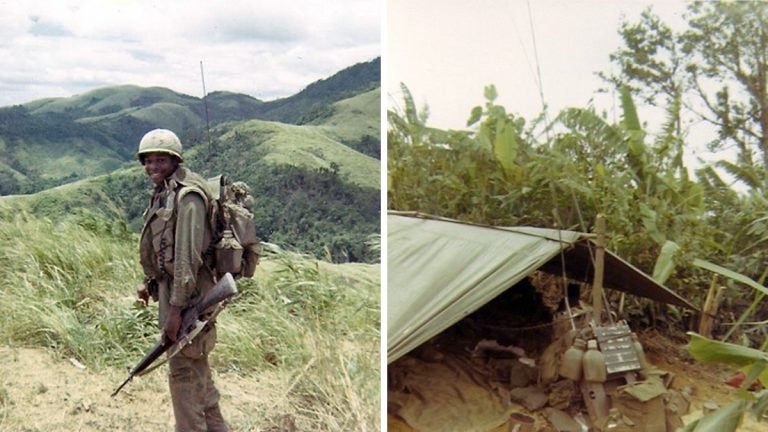

Left: The author's father-in-law, Reginald Waller, is shown as a soldier in the Vietnam War. Right: Waller's equipment is shown set up in a battlefield shelter. (Images courtesy of Reginald Waller)

This story is part of a WHYY series examining how the United States, four decades later, is still processing the Vietnam War. To learn more about the topic, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War.” WHYY members will have extended on-demand access to the series via WHYY Passport through the end of 2017.

—

I do not remember any of the details from the day I saw Oliver Stone’s “Platoon” for the first time. It was 1986. I was 15 years of age. I don’t remember the theater, or who accompanied me there; I don’t remember what I was wearing or how much the ticket cost. I don’t even remember all of the details of the film itself.

However, what I have most readily been able to recall over the years are the memories and feelings I had in response to the film. And in some ways, my memory of those feelings — about “Platoon,” about American empire, about the Vietnam War — were for a long time the total substance of my connection to that moment in my life and to that part of world history.

I am young enough to have missed any conscious understanding of the political contexts for the Vietnam War — no evening news segments; no magazine or newspaper clippings; no primary sources for the war itself. I am also young enough that it had not yet been crystallized in our American history books — no brief synopses of the war or denigrating diatribes on the perilous spread of Communism throughout the region. None of this information filtered into my teen years, so Mr. Stone’s experiences in the war, filtered through his now classic film, filled in the historical gaps for my teenage mind.

There were plenty of characters in the film with whom I might have identified. Growing up in Newark, N.J., in the ’80s also meant that there were even some situations to which I could, at least tangentially, relate. But nothing struck me or stuck with me more than the ultimate plight of Sergeant Gordon Elias, played by Willem Dafoe.

Dafoe was mesmerizing to me as the radical mentor of the younger protagonist, played by Charlie Sheen. He resisted the unrelenting violence of the war, and he paid the ultimate price for his compassion. He was a hero in the film, and he exposed to me for the first time the complexities and the contradictions of war and this great country of ours.

I watched other films later — “Apocalypse Now,” “Full Metal Jacket” — but no film set the stage for me in the way that “Platoon” did. Even still, my connection to this moment in history was limited to the screens and the filters through which I had access. I could never truly understand the Vietnam War — its referendum on the human condition in the 20th century — through these films. They were too far away from my experience. The war was too far away from my memorable history — until I married my wife.

Her father — Reginald S. Waller, Sr. — is a retired sergeant major in the United States Marine Corps. He served in the Vietnam War. I come from a military family, myself, but there is no way to explain my trepidation at the early prospect of meeting the man who became my father-in-law.

He has the most serious countenance I have ever seen. He actually reminded me of my paternal grandfather, my namesake. Both men were silent and serious. Dad Waller’s silence underscores his seriousness, and vice versa. When he speaks, people listen with respect.

I suspect that some of the seriousness in his soul emerged from his experiences in the war. He has never really spoken very much about them, but sometimes, on certain holiday occasions, maybe after dinner or when the game gets to its blowout stage, he will bend my ear, or allow me to bend his. What I can recall most readily of these classified conversations are the memories and feelings that I have of them. They signal that I have become a part of his family, that I am his son. They make me feel closer to him.

But they also make me feel closer to the war in Vietnam, closer to war itself. In these conversations there is no filter; there is no invention; there is no detectable creative license with the history.

I cannot describe for you his experiences in Vietnam — his stories are parts of my memory that only I can access. They aren’t fleeting but they are ephemeral. They are a powerful reminder to me that the history of war is brutal, alarming, and at times surprising in its chronicling of human potential.

His memories, of course, are not mine, but my memories of his relating his most complex experiences are now my very own personal “Platoon.” They have supplanted the film and replaced it with Dad Waller’s documentation of experiences that transcend memory and can never be forgotten.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.