Doing it for the Gram: Showcasing the ‘Imperfect History’ of America’s oldest lending library

The Library Company of Philadelphia partnered with Kwasi Hope Agyeman to make an online “Hidden History” video about an exhibition on historic racism.

Listen 1:54

Kwasi Hope Agyeman records an episode of his virtual series, ''Hidden History,'' at the Library Company of Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Way back in September 2021 — what feels like eons ago on the COVID-19 timeline, during the first delta variant surge — the Library Company of Philadelphia launched “Imperfect History,” an exhibition tracing racial and gender biases in its archive of historic visual material from illustrations and etchings to photography.

With the pandemic still posing a threat for visitors, the Library Company has had to develop ways to get their exhibition in front of people.

Like many cultural institutions, it’s leaned hard on digital tools to reach people who do not feel comfortable attending in-person events and exhibitions. Those include websites, online seminars, and social media.

The country’s oldest lending library is now trying something new and somewhat unique among cultural organizations: partnering with an Instagram personality.

Kwasi Hope Agyeman came to the Library Company this week to shoot an episode of his travel series, “Hidden History.” In a single afternoon, armed with an iPhone, a tripod, and a lot of charisma, he made an episode about some of the big ideas presented in “Imperfect History.”

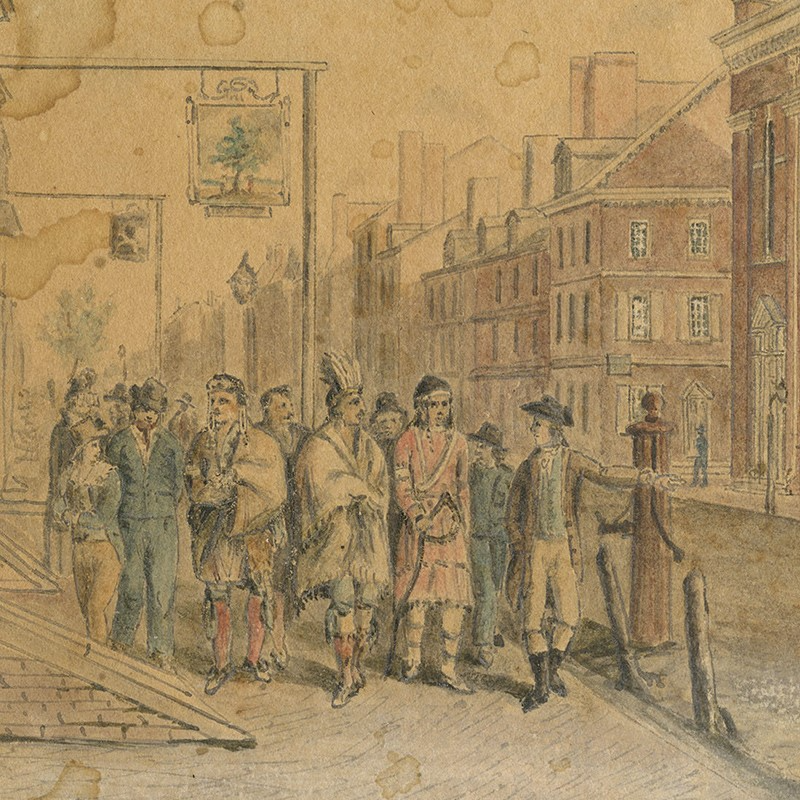

“One thing that really sticks out to me personally is an image of a group of American Indians,” said Agyeman, referring to a drawing of an envoy of Indigenous leaders, who arrived in Philadelphia to negotiate with Congress over land boundaries in 1793.

The image comes courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

“What I really love about that image is that it’s one of the few images, as a historian, that I’ve seen of American Indians having agency,” he said. “They’re meeting with European peers and they’re trying to make some type of business arrangement happen. You have to ask yourself: How come that image is here, but other images are not as publicly accessible that show American Indians had agency?”

Agyeman also highlighted “Primrose: The Celebrated Piebald Boy,” a 1789 image of a Black teenaged slave from the West Indies named John “Bobby” Primrose, who had piebald, a condition that turned portions of his skin white, similar to vitiligo. In 18th century England, Primrose was used in public exhibitions as a medical curiosity.

The question Agyeman explores, as does the Library Company itself, is why is that image of historical racism in the collection?

“We focus on three big things: How is this relevant? What is the big idea, and why does it matter?” he said. “Anyone can watch one of our episodes and get something out of it. You don’t need to be a history buff.”

The nearly two years of the pandemic have tested cultural organization’s online skills, forcing many to go where they had little experience before.

According to a national study, most organizations developed some form of live online streaming content through Facebook or Zoom since 2020, and many created serialized digital content.

Although the study found few organizations have any way to effectively measure social media engagement, most plan to continue developing their online presence beyond the pandemic.

Very few organizations, including the Library Company, had before partnered with someone from outside the organization to tell its story on social media.

“What we haven’t done a ton of is videography, and experiencing history firsthand,” said Chief Development Officer Raechel Hammer. “Having someone come in and allowing our audience, from thousands of miles away or right next door, to see the exhibition through someone else’s eyes, through a young historian’s eyes.”

Agyeman is an academically trained historian specializing in the period of the early American republic, living in New Orleans, and traveling to historic sites around the world to show and tell stories that he finds interesting.

His “Hidden History” posts on Instagram are a series of selfie videos shot on-site at, for example, the living quarters for slaves on a Louisiana plantation, or the mausoleum of Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana. Agyeman says his travel videos get about 60,000 online impressions.

Starting in late 2019 as a side project to his data strategy company Pax Data, Agyeman approached historical sites and cultural organizations to help them reach audiences online through his social media videos.

“Right after the pandemic, it really kind of exploded,” he said.

One of his calls was to the Library Company, where he already had a history.

In 2014, as an undergraduate studying history at George Washington University, Agyeman was accepted into a summer study program at the Library Company to research its collection of African American documents and manuscripts. That experience helped him advance into a master’s degree program for museum studies.

Hammer was happy to bring Agyeman back.

“Having him return to the Library Company after studying here so many years ago gives him the opportunity and gives us the opportunity to widen both of our audiences, expand our network, expand our community,” she said.

Agyeman is also an experienced history marketer, previously working as a tourism specialist for the Chamber of Commerce in Cooperstown, New York. Although his online following is not at “influencer” levels — he has about 1,300 followers on Instagram — as a social media personality, he is able to project his interest in history through the camera.

“It’s so important to have a good storyteller. I think Kwasi is just that,” said Hammer. “We need to be able to tell those stories with passion and excitement. Whether it’s to learn to repeat history, or to not repeat history, we have to be able to tell the stories in a way that will grasp our youngest audiences.”

The Library Company has planned an upcoming event with Agyeman (changed to a virtual event because of the recent pandemic surge) where he will talk with staff curators about “Imperfect History,” and about using Instagram videos not as a pandemic fix, but as an ongoing strategy.

“Gone are the days when you would flip a magazine to make a decision about going somewhere. Gone are the days when you would even ask your friend,” he said. “You want to see someone at the place doing the thing that you want to do, right? That’s what Instagram is all about.”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.