Documentary highlights the efforts to clean-up New York’s Jamaica Bay

For regular attendees to screenings of the Princeton Environmental Film Festival, now in its 10th year, issues of water security are a familiar topic: drought, flooding, melting ice caps and endangered sea life, all a result of human intervention. The festival, which runs through April 10 at Princeton Public Library, offers 25 films and talks with filmmakers and speakers.

“Water is flowing through the festival,” says PEFF founding director Susan Conlon, “from ‘A Simple Question,’ about a sailing adventure and quest to find yourself, to a film about fluoride and another about the world under the sea in terms of sound, from drilling to cargo ships, and how that is affecting ocean life.”

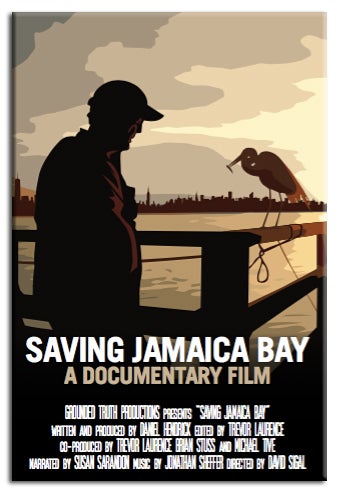

A New Jersey premiere focuses on Jamaica Bay, also known as “Garbage Bay” because, for more than 100 years, it’s where New Yorkers put the things they didn’t want. “Saving Jamaica Bay” screens Thursday, April 7, 7 p.m.

A New Jersey premiere focuses on Jamaica Bay, also known as “Garbage Bay” because, for more than 100 years, it’s where New Yorkers put the things they didn’t want. “Saving Jamaica Bay” screens Thursday, April 7, 7 p.m.

Part of Gateway National Recreation Area and the largest open space in New York City—bigger than three Central Parks, three Prospect Parks and three Van Cortlandt Parks combined—Jamaica Bay is cleaner now than a generation ago, although it still has a way to go, according to the film. And though they may not know it by name, travelers landing in or taking off from JFK International Airport have seen the bay through the windows of planes.

“There are more species of wildlife here than in the Adirondacks or the Catskills—more than 325 bird species and 100 types of fish have been documented—and it’s accessible by taking the A train and walking a half mile to the visitor center,” says actress Susan Sarandon, who narrates the film.

Jamaica Bay is so rich in biodiversity because it offers both salt and freshwater habitat, and is along a migratory bird path. Owls, osprey and horseshoe crabs are shown making their homes here, as well as peepers, gray tree frogs, egret, ibis, yellow crowned night heron and terrapins—a sign of a healthy bay, except that the terrapins are often found on the airport runway and the osprey like to nest on towers.

For decades, landscapes of garbage, abandoned boats, piers and docks—not to mention the occasional gangland victim—were dumped here. In the era of the horse-drawn buggy, Dead Horse Bay was thus named because barges dumped equine remains. Four sewage treatment plants discharged effluent, and in more recent times, as jumbo jets spewed noise pollution overhead, plans were underway to fill in the wetland and build runways needed for future air traffic.

“There are no easy answers,” says Producer Daniel Hendrick, who lives in Queens, a few miles from the bay. “In the ’70s or ’80s, you wouldn’t dream of hanging out there. It was a place for abandoned cars. Robert Moses put four housing projects out there, as a means of warehousing New York City’s poor, with no means of transportation.”

Before the environmental movement, wetlands and salt marshes were seen as wastelands. At the same time, the natural beauty along the water was appreciated and resorts developed, along with ferries to bring people to the area known for some of the best fishing on the east coast.

Fishermen built shacks along Jamaica Bay that became year-round homes, and a community developed among those who shared a love of the outdoors. Many of the homes are lived in by heirs to the original owners, and these residents became environmental allies when, in 1995, they began noticing the marshes disappearing. Following Hurricane Gloria and the Nor’easters of 1991 and 1992, homes began flooding.

Today, there are beaches where walkers crunch over green glass bottles, a remnant of an era before the proliferation of plastic bottles. The beach means different things to different people, and one man’s garbage is another woman’s spiritual offering. In communities surrounding Jamaica Bay, 130 languages are spoken and dozens of religions are practiced. We see Hindu worshippers bringing prayer flags, incense, saris, figurines of deities and multicolored flowers, giving their offerings to their gods. In the end, all of this is left behind in the water. As a result of the film, a group has formed to help address the issue and raise awareness about the need to keep such items out of the water.

Filming had begun before Hurricane Sandy, but during the storm Hendrick kept the cameras rolling. We see residents shoring up in the days leading up to the disaster, hoping for the best, then evacuating in canoes and returning later to rebuild their homes, some from scratch. “It was horrible to watch and be in the middle of, but at the end of the day it underscores the importance of caring for nature,” says Hendrick. It is the restoration of the salt marshes that will help protect the bay from future storms on the magnitude of Sandy. (Note: the crew did follow evacuation orders, but residents and firefighters contributed footage of the disaster.)

We see the resiliency of the residents as they return to dilapidated homes that, earlier in the film, looked like seaside retreats. “The overwhelming majority love living there, being by the water and only an hour from Manhattan—where else can you have that?”

Through the sponsorship of Church & Dwight, the Nature Conservancy, the Whole Earth Center of Princeton, Friends of the Princeton Public Library and NRG, all PEFF screenings are free.

Complete list of festival films

______________________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.