Divvying up the burden in special exception zoning

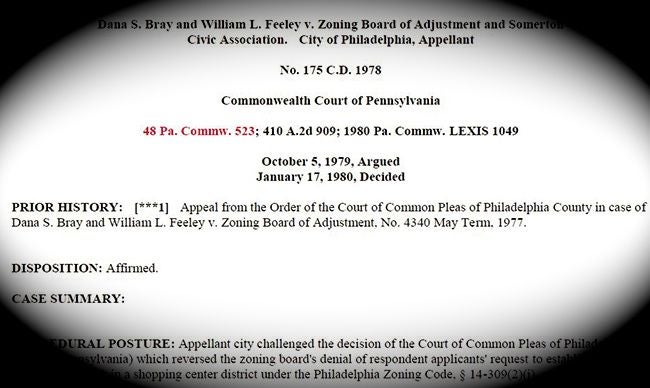

In a previous post, I alluded to uncertain requirements for those who want to object to development proposals in special exception cases. It was later called to my attention that the special exception or certificate zoning process in our city is controlled not only by the zoning code, but also by case law. One case in particular, Bray v. Zoning Board of Adjustment, has set the precedent regarding evidence requirements for both applicants and objectors.

A brief explanation of that case may help clarify what’s required of developers seeking special exceptions as well as parties who object to their proposals.

The case, which was decided in the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania in 1980, dealt with a proposed roller-skating rink in an Area Shopping Center District. When the developer initially brought the proposal for the rink to the ZBA for certificate approval, the application was denied. (Note: a certificate in Philadelphia is the same as a special exception in the rest of the state. The reformed code has done away with the term “certificate.”)

The ZBA’s decision was based on a claim that the applicant had not satisfied its burden of evidence. The case then went to the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia County, which reversed the ZBA decision. It was then appealed once more, this time to the Commonwealth Court, which upheld the decision of the Court of Common Pleas.

The language of the Bray decision was called “eloquent” in a later case which cited it, though to the mind of a layman such as myself, it’s a bit convoluted. Nevertheless, I’ll give you my layman’s understanding of the court’s decision.

- Even though the Philadelphia Code says that the party applying for an exception has the “duty of presenting evidence relating to the criteria set forth herein,” the court took note of a “rational distinction” between the burden of persuasion and the duty of presenting evidence. The latter duty can shift from the applicant to the protestant/objector, the court said.

- The court summarized the specific factors to be considered by the ZBA in special exception cases, which can be found in §14-1804(1) of the Philadelphia Code, like so: “(a) traffic congestion, (b) fire and safety danger, (c) overcrowding or concentration of population, (d) impairment of light and air to adjacent property, (e) adverse effect on transportation or other community facilities, (f) detriment to public health, safety or general welfare, (g) harmony with spirit and purpose of the zoning code, and (h) adverse effect upon redevelopment plan or comprehensive plan.”

- The burden that the applicant actually has is the burden of showing that the proposal complies with the terms of the ordinance. That is, the applicant must show that his proposal meets the specific criteria (a-h) laid out in the part of the code governing special exceptions. Essentially, a use allowed by special exception is a use that is allowed as a matter of course as soon as certain conditions are met. As the court put it, “The important characteristic of a special exception is that it is a conditionally permitted use, legislatively allowed if the standards are met.”

- Specificity of terms is the most important issue. As the Bray court quoted from an earlier case, an applicant cannot be expected to “negate every conceivable and unvoiced objection to the proposed use.” So for a few of the criteria listed above, the burden of evidence shifts to the objectors. Those include (f) and (g), detriment to public welfare and harmony with the spirit of the zoning code. An applicant is not expected to carry the burden of proof when a criterion is overly vague.

- In sum, the court ruled that, (1) the applicant has both the duty of presenting evidence and the burden of proof regarding specific requirements in the ordinance, (2) objectors have both the duty and the burden regarding general detriment to the public welfare, health, and safety, and (3) objectors have both the duty and the burden when it comes to “general policy concern,” i.e., harmony with the spirit of the code.

I ran all of this by a few Philadelphia land-use attorneys, and they helped tease out the implications of the decision. Both Richard C. DeMarco, of Klehr Harrison Harvey Branzburg LLP, and Cheryl Gaston, president of The Lawyers’ Club of Philadelphia, emphasized that the initial burden of evidence is on the applicant. The applicant always has to demonstrate that his or her proposal meets the specific criteria listed above.

However, that burden is pretty light. Gaston said that it amounts to applicants having simply to show that their proposal would put “no extraordinary burden” on traffic congestion, overcrowding, community facilities, and the like.

“They don’t have to do a whole lot to prove that they’ve met it,” Gaston said. That’s because, as mentioned before, special exception uses are essentially regarded as permitted uses. Legally, there is no extra decision for the ZBA to make once the applicant demonstrates that his or her proposal meets the specific criteria. The applicant may then go forward by right, unless objectors can show that the proposal will be a detriment to public health, safety, and welfare, or that it’s out of harmony with “the spirit of the code.”

“The applicant’s burden is pretty easy,” Gaston said. “The objectors’ burden is very, very difficult.”

Once the applicant shows that his proposal meets the specific criteria, the burden shifts to the objectors, if there are any, to show that it doesn’t meet the general criteria. In order to block a certificate, objectors must present proof that the applicant’s proposal will cause a real, predictable detriment to public welfare.

“[The proof] can’t be fanciful,” Gaston said. “It has to be real.” In other words, the objector’s burden is to present specific evidence showing that the applicant hasn’t met the general criteria. And that’s a difficult thing to do.

“The protestant does have a heavy burden to show that the use is contrary to the general health, safety, and welfare,” DeMarco said. And that’s the way it’s intended to be. The certificate, or special exception, is intended to be a minor, extra control on a use that is allowed. It’s not like a variance, where an applicant proposes a use that is explicitly disallowed.

In fact, an objector’s best chance of stopping the approval is not to meet the high standard of evidence for the general criteria.

“The only way you [as an objector] can win a certificate case,” Gaston said, “is if you prove that, or at least assert that, the applicant has failed to meet their initial burden. Because once the burden shifts, you don’t have much.”

So, objectors, rather than waiting until the very heavy burden regarding the general criteria falls to you, you have a better chance of trying to show that the applicant didn’t meet his own, lighter burden. Gaston pointed out that many applicants never actually present evidence to show that their proposal meets the criteria, since it’s usually assumed that the use is allowed. If objectors can demonstrate that the applicant didn’t meet his burden, they can stop the project. But if the applicant has met his burden, by having some sort of presented evidence on record, the application is virtually approved.

“If [the burden] shifts,” Gaston said, somewhat hyperbolically, “you’re done.” She further explained that the special exception provides a forum for objectors to voice their objections, but with the understanding that the applicant has permission to move forward.

“They at least have an opportunity to come and put their objections on the record,” Gaston said, “but the chances that they’re going to be able to keep back the applicant who’s met his requirements are pretty low.”

Contact the reporter at jaredbrey@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.