After three-year debacle, Delaware has plan to remove lead from school drinking water

It’s taken two rounds of testing, and the process was marred by sloppiness and a lack of transparency, but a $3.8 million “shot of adrenaline’’ is coming.

Listen 2:04

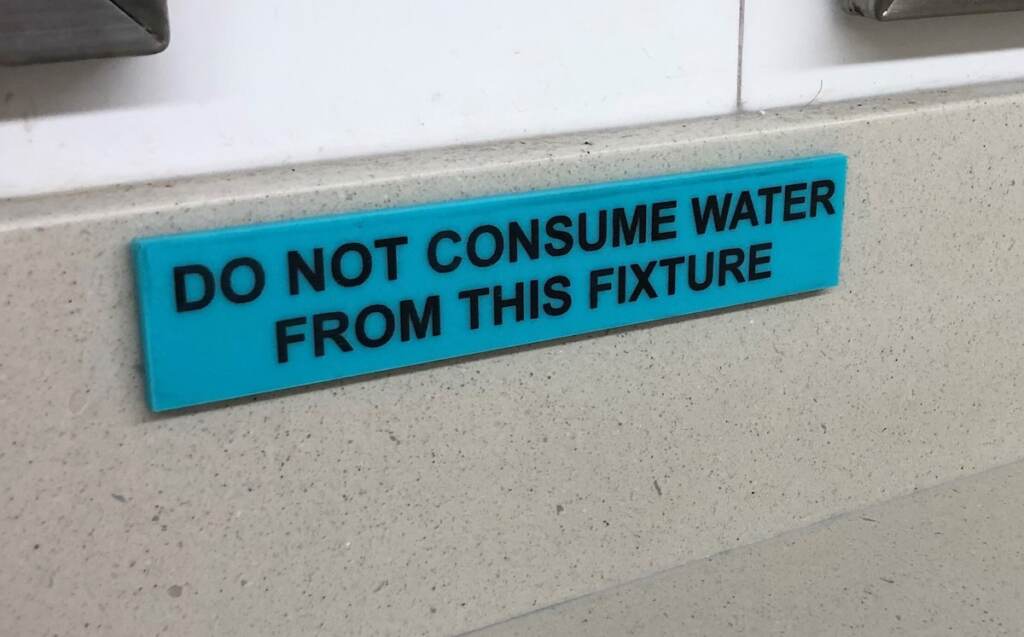

A student at Smyrna High School fills up at a filtering station. (Courtesy of Smyrna School District)

In April 2020, Delaware education and health officials delighted in being awarded a $209,000 federal grant to test for lead in school drinking water.

The safety of fountains and spigots in the roughly 200 public schools — many with lead piping more than a half-century old — could be evaluated, and school leaders could devise a plan to remediate sources of contamination.

More than three years later, a solution to protect more than 142,000 kids plus thousands of staffers and visitors now appears to be imminent: The state will spend $3.8 million to install filtering stations in schools. The goal is one station for every 100 kids.

“This is a shot of adrenaline into the system to get districts moving in this direction very quickly,’’ Education Secretary Mark Holodick said.

Even Amy Roe of Lead-Free Delaware, a frequent critic of how Delaware has conducted testing and communicated results, agrees the step is a positive one to address high levels of a metal that causes developmental delays and other health maladies in children.

“I’m ecstatic that we’re initiating this. This is what we asked for, right?’’ Roe said.

But getting to that injection of cash and installation of filters could be compared to driving on a bumpy road that’s pockmarked with potholes.

From the outset, the limited testing that began in December 2020 was at best a botched effort, as samples were taken by improperly trained custodians and janitors as schools grappled with pandemic-related closure and interruptions.

Then, once the results were tabulated, the state didn’t provide the results to schools until May 2022 and the public didn’t learn about it for another five months. And that only happened after Roe and Lead-Free Delaware came across the data and informed the media.

Matters only deteriorated from there.

Compounding the sloppiness and lack of transparency on the state’s end was the fact that lead was detected in the vast majority of schools, and in alarming amounts at several buildings.

A WHYY News analysis of the 1,600 samples revealed that lead was detected at more than 7.5 parts per billion — the level the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency set for cutoff — at a total of 149 sites in 49 schools.

The faulty testing, failure to notify the public, and the high levels up and down the state led to an outcry from Lead-Free Delaware and other advocates for children.

State Sen. Sarah McBride and other lawmakers hosted a virtual town hall where residents demanded answers, and earlier this year an official Senate committee hearing where Holodick and other officials testified under oath. Holodick, who didn’t take the post until January 2022, said his department assumed full responsibility for the debacle.

All that turmoil and controversy spurred the state to initiate a second and far more thorough round of testing over the winter. Officials allocated up to $1.5 million to re-test every source that had exceeded 7.5 parts per billion as well as every consumption point statewide.

Testing had been expected to wrap up by March, but it’s not quite finished yet as the school year comes to end. The state, true to Holodick’s pledge, is posting these results on a web site that gets updated weekly as results are tabulated.

The new results, like the old ones, continue to show unacceptable lead levels at dozens of schools. An analysis of the data by WHYY News shows that of the nearly 16,000 samples taken so far:

- 771 (4.8%) had lead detected at or above the 7.5 parts per billion, the level set for shutoff and remediation.

- 4,011 (25.1%) had lead detected below 7.5 parts per billion but above 0.6 parts per billion. The state says 0.6 parts per billion is the lowest its testing equipment can detect the substance.

- 11,179 (70.1%) had no lead detected.

Holodick said the results were not unexpected.

“The good news, I believe, is that we don’t have a statewide or even for that matter, district-wide or school-wide issue in regard to elevated levels of lead in water,’’ Holodick said. “What we have are a rather small percentage of consumption points that are above 7.5 parts per billion.”

‘Need to work toward non-detectable levels at all points’

Holodick isn’t waiting, however, to implement a solution long suggested by Roe and other authorities on safe water, including Environment America, which publishes a scorecard of all states for their management of lead in drinking water in schools.

To that end, this spring Holodick asked the General Assembly for $3.8 million in the state’s fiscal 2024 budget for filtering stations. The legislative Joint Finance Committee that writes the budget has approved the amount, and Holodick expects the money to be available after July 1 once lawmakers approve the budget.

The state’s 19 school districts and roughly two dozen charter schools will be allocated money, based on enrollment, to install filtering stations, he said.

“We need to work toward non-detectable levels at all points, and that’s where this filter-first approach comes in,’’ said Holodick, who added that “there’s no other state in the country that has ever done an entire sampling of every consumption point in every public school. Not even close.”

Roe says $3.8 million isn’t quite enough. Lead-Free Delaware put a $5.7 million price tag on how much it would cost to have one $3,000 bottle station for every 100 students, including preschoolers in public school facilities, plus one in each nurse’s office and teacher’s lounge.

“It’s not as much as we asked for, but I’m heartened we’re taking steps,’’ Roe said.

Holodick said many schools, especially in the upstate Brandywine district, already have installed filters and that districts are welcome to use their own funds to augment the state’s contribution.

Filtering stations ‘should take it down to undetectable levels’

The state has also contracted with Natalie Exum, a public health professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who specializes in safe water issues, to advise on the testing and remediation effort.

Exum told WHYY News that installing filtering stations, properly maintained, is a practical and effective solution.

“It should take it down to undetectable levels, meaning the analysis that we can do with the technology that we have cannot detect it,’’ Exum said. “It may be there at some very, very trace amounts, but we cannot detect it because it’s so low.”

Exum said parents of schoolchildren should not be alarmed by Delaware’s findings.

“I would say what we’re seeing in the Delaware schools is actually normal, if not extremely normal for a part of the country that has very old drinking water systems and very old pipes,’’ Exum said.

The scientist said the results signify that contaminated service lines to fountains and spigots are not a chronic problem in Delaware schools.

“So it’s actually a better scenario because then what you can do is go into these sites where you know there’s an issue and instead of ripping the whole pipe out of the wall, what you can do and what Delaware is doing is putting on a filter at the very end of that pipe,” Exum said.

That gets the lead out and officials can have “schools continue to function and your water keeps flowing. And the water coming out of that is safe to drink.”

‘Kids enjoy being able to bring their water bottle and refill it’

Roger Holt, director of operations for the 6,000-student Smyrna School District that encompasses southern New Castle County and northern Kent County, welcomes the expected state money.

“We’re absolutely excited,’’ Holt said. “I think it’s an excellent, proactive approach, a good thing for all school districts. We’re looking forward to being able to use those funds to install more of the filtered filling stations and being able to do some retrofitting in some areas in our schools for some of the fixtures that we currently have.”

Smyrna, like most districts, has replaced some fixtures and/or installed filter stations at six sites where lead was detected at high levels in its eight schools.

“We feel full confidence that we’re mitigating the risk appropriately for the school district,’’ Holt said.

Holt said each school already has a couple of filtering stations and more will be added.

“They’re extremely popular’’ with students and staffers, Holt said. “It’s chilled water and it’s filtered. And they are allowed to carry water bottles in the school. So they enjoy being able to bring their water bottle and refill it throughout the day as they need.”

Exum said more filtering stations only adds awareness to the issue of safe water.

“It’s going to bring into the consciousness of school administrators, facilities, managers, teachers, children that when you walk past a fancy-looking filter station, you’re going to want to put your water bottle underneath one of those as opposed to those kind of old rusty water fountains,’’ Exum said.

Roe, who has a doctorate in environmental policy, only wishes that Delaware hadn’t wasted so much time before taking decisive action, and that her group hadn’t needed to prod the state into doing the right thing for children.

“Delaware spent six extra months and a million-and-a-half dollars to re-sample all these schools to prove something that we already knew, which was that we had lead in the drinking water and we needed to do ‘filter first,’’’ Roe said. “So, you know, we’re getting to where we need to be.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.