Dear Suburban Moms: A note, a library, and a shared responsibility

Listen 6:04-

Bonnie Koss arranges gifts for the teachers of Richard Wright elementary. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Teachers at Richard Wright elementary school receive donated gifts from parents and supporters in the suburbs of Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Suburban schools donated their extra supplies to Richard Wright elementary school. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Each student at Richard Wright elementary school receives a book, candy cane, and pencil donated from suburban parents. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

(From left) Gwenn Mascioli, Bonnie Koss, and Nicole Scherer are parents from the Paoli-Wayne area who donate time to gather resources for Richard Wright elementary school in Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

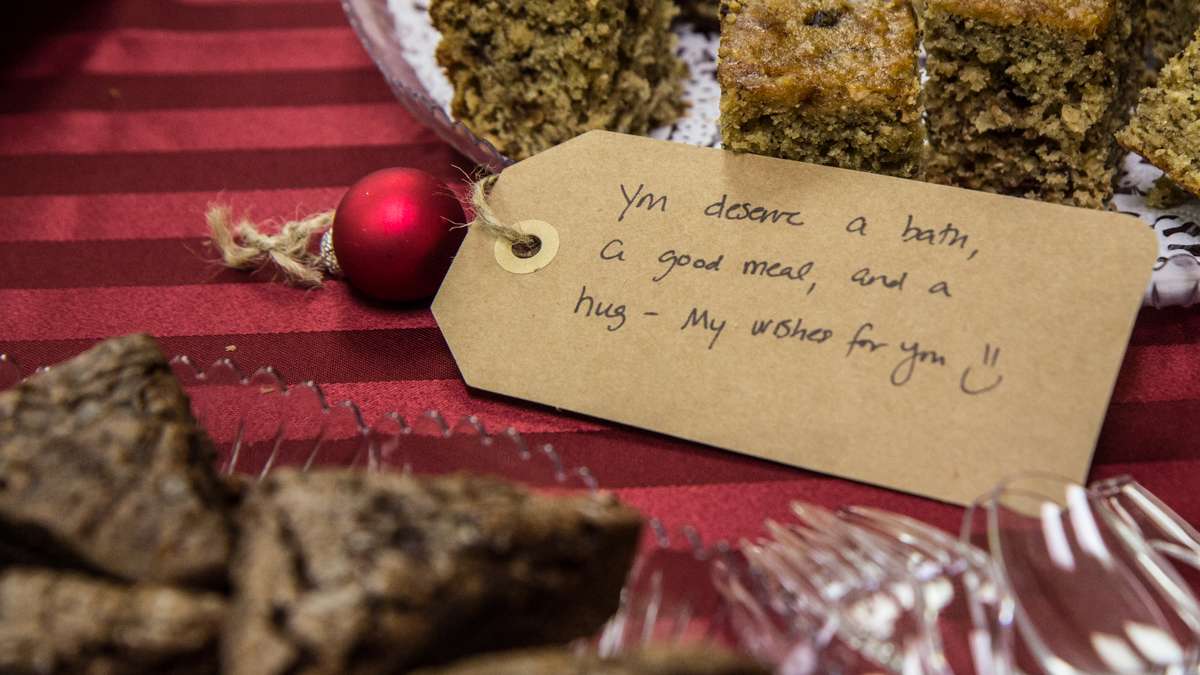

Richard Wright elementary teachers are gifted baked goods from supporters outside the city. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Richard Wright elementary school in North Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Richard Wright elementary teachers are gifted baked goods from supporters outside the city, and are decorated with supportive Christmas tags. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Students at Richard Wright elementary school celebrate college t-shirt day with t-shirts donated from supporters outside the city. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Parents from the Paoli-Wayne area donated time to gather resources like furniture for a teacher’s lounge at Richard Wright elementary school in Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Gwenn Mascioli and other parents from the Paoli-Wayne area work to keep Richard Wright elementary school in Philadelphia stocked with school supplies. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

In 2013, a group of suburban women saw an empty school library in Philadelphia. They’ve been there ever since.

Our story starts with a note.

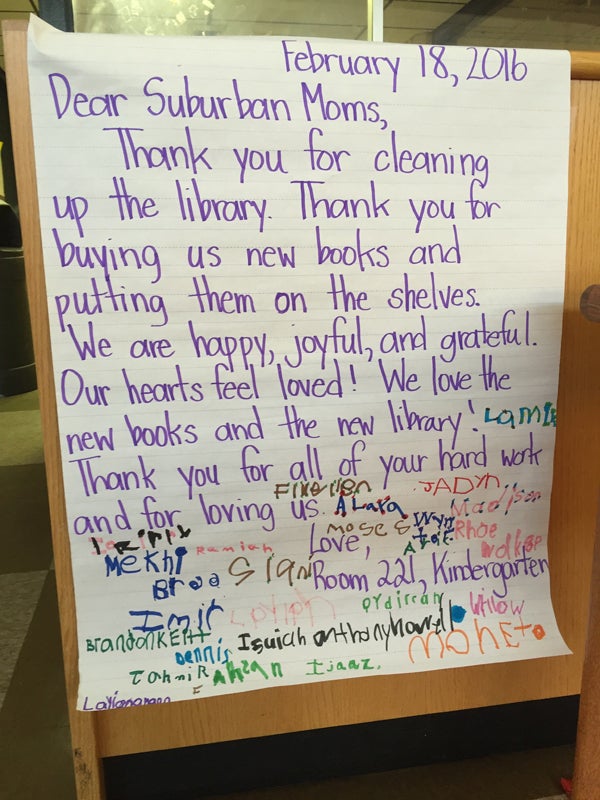

I spotted it while wandering through the library at Richard Wright Elementary, a kindergarten through fifth-grade school in Philly’s Strawberry Mansion section. Even among all the funky, funny items you tend to find on the walls of elementary school, this note stood out.

Dear Suburban Moms. Thank you for cleaning up the library. Thank you for buying us new books and putting them on the shelves. We are happy, joyful, and grateful. Our hearts feel loved! We love the new books and the new library! Thank you for all your hard work and for loving us.

It was signed by Room 221, with the names of about 25 kindergartners scrawled underneath in magic marker. It was a lovely little token of gratitude. But what stuck with me was the intro: “Dear Suburban Moms.”

Something about that moniker felt off, even uncomfortable. In its context, the name seemed specially designed to emphasize difference.

Richard Wright is the demographic stereotype of an inner-city school. About 85 percent of students are economically disadvantaged, according to school district data. The school sits in a ZIP code where the median household income is $23,380. Over 90 percent of the students are African-American.

Who parachutes into a low-income urban community and calls themselves Suburban Moms? And why?

That question led me to a woman named Bonnie Koss.

Koss is indeed a suburban mother of four — a stay-at-home mom with a part-time therapy practice. Like a lot of suburban mothers, Koss had been a city mother for a time.

She lived in the Northwest Philadelphia neighborhood of Mt. Airy and adored it, smitten with its reputation as a purposefully integrated neighborhood. When her oldest was about to start kindergarten, she hoped that she and the rest of her middle-class neighbors would send their kids to the local public school. Perhaps they could improve it through volunteerism and fundraising, she thought.

Her friends shook their heads. It was a nice idea, but no one wanted their kid to be the “sacrificial lamb.” Koss agreed. That year the family bought a house in the Tredyffrin-Easttown School District, which has the second-highest median income among Pennsylvania’s 500 school districts.

“When we moved, I definitely had a lot of regret,” she says. “And it stuck with me.”

Fast forward a decade

By this point Koss was a stay-at-home mom. Partly out of boredom, she started organizing get-togethers with other neighborhood moms. At first it was for fun, a standard girls’ night out. Then they decided they should orient each gathering around some sort of charity. They called the group Social FUNdraising and Gatherings.

In late 2013, they decided that for one of these gatherings everyone should donate supplies to a needy school in Philadelphia. Koss didn’t know any so she called up the school district and basically said, point me to your neediest school. After some bureaucratic wrangling, the district directed her to Richard Wright.

Eventually she and a few other women rolled into Richard Wright School in North Philadelphia with mini vans full of school supplies. Perhaps out of obligation or courtesy, they were offered a tour of the building. Perhaps out of obligation or courtesy, they said yes.

The tour wound its way to a large, seemingly abandoned room in the center of the second floor. The bookshelves that lined the room were barren, with the exception of a single, outdated encyclopedia set.

“They said, This is our library,” she recalls. “And it was like, how could this be your library?”

There are 220 traditional public schools in Philadelphia serving 134,000 students. There are a total of six school librarians.

The dearth of staffed, functioning school libraries is just one of the stark differences between Philly schools and those in wealthier suburbs. For Koss, this image seemed to crystallize the imbalance.

“Once I saw it I couldn’t unsee it,” she said.

The next chapter

Koss and her fundraising friends went on a book-gathering binge. To date they’ve collected, by their estimation, 80,000 used children’s books. (Coincidentally, that’s the same number of books the 2016 DNC host committee recently pledged to donate by way of a $750,000 check.)

Initially when they ferried the books back and forth the suburban parents noticed the new arrivals weren’t being shelved. The staff, they were told, didn’t have time to unpack and organize them. So they started to shelve the books, which brought them into the school almost every day on a rotating basis. Suddenly there were a lot more things that Koss and her friends couldn’t “unsee:” the chronic classroom supply shortages; the absence of a teacher’s lounge; the inability to pay for field trips.

Social FUNdraising and Gathering quickly mushroomed in size and scope. A Facebook group dedicated to the effort now has more than 1,000 members. When the original principal at Richard Wright moved to the nearby Edward Gideon school, the suburban volunteers took on two sites.

Teacher luncheons, class trips, pallets of paper — when Richard Wright or Edward Gideon needed something, Koss and her friends would throw up a Facebook alert. And the suburban abundance would roll in.

The library at Richard Wright — described by one teacher as a “desert” in its former state — now brims with books. There’s a coffee machine for the teachers in an upstairs lounge that once overflowed with unused junk. The list of improvements goes on and on.

In three short years, this group of suburban parents — who had no affiliation with either school and almost no relationship with the community — has become the de facto parent-teacher organization for schools that didn’t otherwise have one.

“We’re not doing anything miraculous,” said volunteer Nicole Scherer. “We’re just trying to help as much as we can and solve little problems.”

Parents make the difference

You can measure inequity in a lot of ways. There are, of course, the statistics of student poverty and per-pupil spending. But Jeannine Payne, the principal at Richard Wright, said one of the crucial differences between the haves and the have-nots is the often-nebulous networks of supporters that privileged schools can lean on when needed.

“It manifests as little things,” said Payne. “But let’s talk about the meat of things. These are the things that differentiate charter schools, suburban public schools — this expectation of parent involvement.”

Payne has taught or been an administrator in North Philadelphia for almost 20 years. Growing up, she attended some of the city’s top special admissions schools. She knows well the difference between the two.

“All of our magnet schools have involved parent organizations,” Payne said. “A large number of the schools in our more affluent areas in the city have parent groups that they can help. And it just seems like when you get to areas with less family resources, you also get perceived less involvement with families.”

Payne stretched the word “perceived” because she knows this is a tricky point. She isn’t saying the parents at Richard Wright don’t care about their kids’ school. A recent winter concert at the school, for instance, was standing-room only because of massive turnout.

But there is, said Payne, little history of a sustained, organized parent group at her school. She and the teachers at Wright say that’s common in the city’s most disadvantaged neighborhoods. One teacher said that, across multiple decades and four schools, she’d never run into a PTA.

Payne knows the suburban moms won’t stay forever. She hopes they’ll leave behind a structure for parental involvement that can sustain Richard Wright in the future. Perhaps the parents of Richard Wright won’t have the means to provide as much, but they can still give.

“I don’t think we’ll ever be able to replace suburban moms,” she said. “But I believe the core of being able to provide service, being able to support the students, that idea can take root and be a part of the school.”

And this represents the heart of the dilemma for a principal in a disadvantaged school. You want to accept help where you can get it. But you also want to build something from within that can last.

“What I struggle with is making that balance between utilizing them for things we can’t do on our own, but not becoming dependent on them for things that I want us to develop as a school community for ourselves,” Payne said.

Outreach to partner up

Bonnie Koss sees things much the same way.

This fall she decided for the first time to reach out to parents of children at Richard Wright and Edward Gideon and see if they might join the group. Despite spending three years and countless hours in North Philadelphia, Koss and her friends had yet to establish any solid ties to the broader community.

During this fall’s back-to-school night, Koss set up a table complete with the usual enticements: fruit, candy, and, of course, books. She made small talk with the parents as they passed, all the while collecting email addresses. It felt like a start.

Afterward she contacted dozens of parents and invited them to join the parents group. She’s yet to receive a reply.

As I eventually found out, Koss and her friends never called themselves the suburban moms. The name started organically among a group of teachers and stuck. Koss got a chuckle out of the moniker at first, but recently it’s been harder to smile.

“It makes us sound like we’re just a group of suburban moms and I want us to truly be a partnership of parents,” she says.

Lately Koss has hosted a series of forums in the suburbs on racial injustice. She’s tried to think more deeply about what it means to be a group of wealthy, white volunteers in a school that is overwhelmingly poor and black. She’s mediated on the part she’s played in exacerbating inequity, moving her family from the city to the suburbs explicitly for the purpose of finding that “good” school district. She’s reading. She’s learning. She does not yet have the answers.

“I’m doing more and more research on the bubble that I live in,” she said.

The suburban moms I found on the other side of that thank-you note were nothing like the ones I imagined. They hadn’t parachuted in. They weren’t jetting through the city to get some of that feel-good charity glow and leaving just as fast. They were trying to do work that mattered.

The holidays are peak season for showy, one-shot charity. Everyone wants to buy a kid a bike or present some oversized check. This was the opposite.

And yet that name “suburban moms” also spoke to the difficulties of moving beyond labels and expected boundaries. They were still outsiders. You can’t erase that with a table at back to school night.

The work continues

Gladys Woodberry is a longtime volunteer at Richard Wright, part of a core group who’ve maintained a presence in the absence of a formal parent organization. Most days you can find her at the front of the school signing visitors in. She’s sent three grandchildren through Richard Wright and spent a decade walking its halls.

She’s one of very few parents or grandparents who even know the suburban moms on a passing level. When she first saw them, she assumed they’d come and go.

“I was like OK. They just came to do something,” said Woodberry, who has lived in Strawberry Mansion for 58 of her 65 years. “And then, every time I look up, here they are.”

As the women kept returning, she realized they weren’t there just to “do something. They had something to do.”

There’s an important difference, Woodberry said.

“When you’re just doing something, you want to be seen,” she explained. “When you got something to do, you’re doing it ’til it’s done.”

So when will the suburban moms be finished? Perhaps when no one calls them the suburban moms anymore.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.