Cranes, bicycles, and Beethoven’s 6th: Philadelphia Orchestra remembers 1973 in Beijing

Reporters from Chinese media invited to Philadelphia, ask the Orchestra about U.S-China relations, and what China was like back during their first visit.

Reporters for various Chinese media outlets came to the Kimmel Center Friday to sit with musicians who were on the historic China tour in 1973 (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

After 46 years of the Philadelphia Orchestra visiting China, China has visited them.

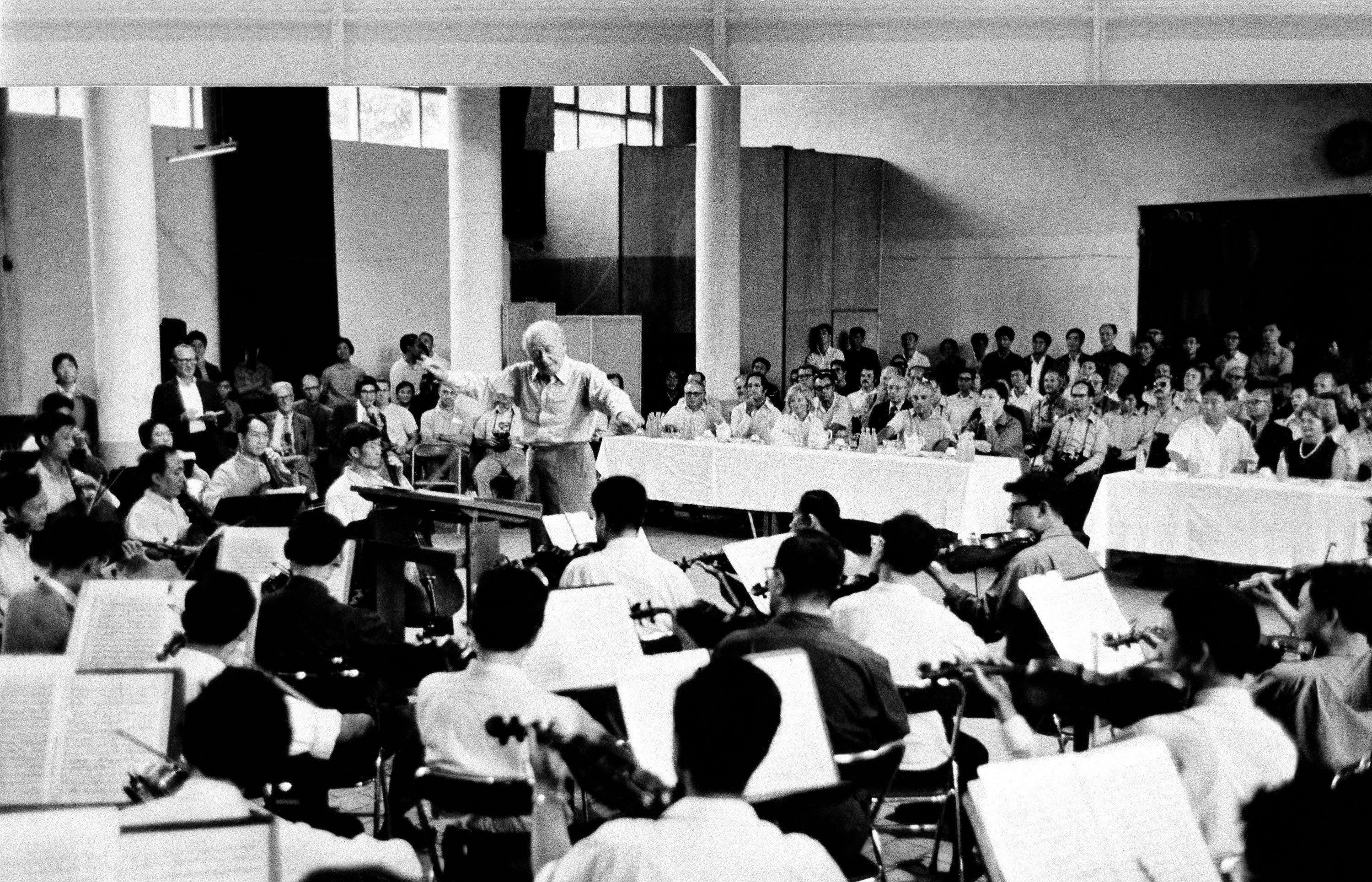

A dozen reporters for various Chinese media outlets came to the Kimmel Center Friday to sit with musicians who were on the historic China tour in 1973, the first American orchestra to visit the People’s Republic at the urging of President Nixon.

The reporters skewed younger; none seemed old enough to have been alive in 1973. They wanted to know what China was like back then. “What programs have you seen developing in China over the years?” a reporter asked.

“The cities are huge!” said violist Renard Edwards. When he first visited China with the orchestra in 1973, Beijing was in the midst of the Cultural Revolution. It was not the city of skyscrapers that it is now. Most buildings were low-slung and wooden, save the wide-open Communist government plazas. People mostly got around with carts and bicycles.

“My memory of the first tour was seeing this incredibly large country that was quite rural,” said violinist Davyd Booth. “In Beijing I remember farms and people with carts.”

Violinist Booker Rowe remembered everyone wore the same clothes in 1973, the standard-issue Zhongshan suit preferred by Chairman Mao. “Greys and blacks,” he said. “Baggie pants.”

Ryan Fleur started visiting China seven years ago in his capacity as executive vice president of orchestra advancement, and watched it undergo rapid construction — a “city of cranes.” “The biggest change now is the cranes are gone,” he said. “The construction stopped and now railroads are being built, the next level of development.”

“The bicycles are gone, too, and that’s the problem,” said Nicholas Platt, the former State Department diplomat who in 1973 was in charge of opening the first American liaison office in China.

“We were not able to have casual conversations with Chinese. It was frowned upon by the government,” he recalled. “If you had a conversation on the street you would be reported by the old ladies on the Revolutionary Committee. But if you got on your bicycle, people would come bicycling up and have a conversation with you.”

Platt advised George H.W. Bush in 1974 just as the future President was about to take over as chief of the liaison office: “He asked, ‘What’s the first thing I should do in Beijing?’” said Platt. “I said, ‘Buy a bike.’ And he did.”

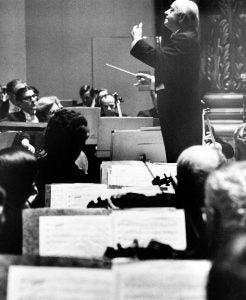

Platt, the musicians, and the administrator sat as a panel under a painted portrait of Wolfgang Sawallisch, who led the Orchestra through China three times, in 1993, 1996, and 2001. That first tour, the 1973 icebreaker, was led by conductor Eugene Ormandy.

“Madame Mao [wife of Chairman Mao] was in charge of culture, and wanted Beethoven’s 6th Symphony. Ormandy didn’t like Beethoven’s 6th,” said Platt. “I was told just before the plane arrived there was a top-level request for Beethoven’s 6th. My job was to convince Ormandy.”

Platt realized he would have to do some fast talking to break the ice with Ormandy.

“Let me explain to you why the Chinese think this is an important symphony,” Platt told Ormandy while seated next to him on the airplane. “Most Chinese music is program music: it deals with a specific event or scenery or poetry. Beethoven’s 6th is one of the greatest pieces of program music ever written. It’s all about life in the countryside.

“Here is this government that has come to power on the backs of a peasant revolution,” he continued. “They are very interested in the way rural life is depicted. In the 4th movement you have a big storm. The Chinese believe that is the revolution.”

Platt didn’t know if any of this was true: “I was actually making this up.”

It worked. “Ormandy looked at me and said, ‘When in Rome, we should do as the Romans wish.”

The Orchestra was actually the third American delegation to go to China in 1973, behind sports teams. Earlier that summer a swimming team and two basketball teams — male and female — had visited with great interest by the Chinese.

Before ever playing a note, the Orchestra first dazzled the Chinese with a Frisbee. When they arrived at their hotel, a few musicians stepped outside to throw one around. The Chinese had never seen a Frisbee before.

“I thought, ‘These guys are really good at connecting with people,’” said Platt.

During that first tour audiences were enthusiastic. Performances were followed by spirited applause, and the musicians were advised they should applaud back.

“I thought it was an excellent idea,” said Rowe. “The composer is the first level of communicating. Once he has written the music we as performers have to translate it. It goes through us to the audience. If someone doesn’t come to hear it, it’s meaningless. It’s dead. It comes to life by being received by the audience. They should be given as much credit as we are given.”

Once, in an attempt to stretch his legs on a day off, Rowe remembered taking a walk through Beijing.

“We’d been told not to walk in groups of three or four, and not less than groups of two,” he said. “At the time there were block captains. If they saw something out of the ordinary they would report it to their superiors. If that happened, it might create an international incident.”

Rowe couldn’t find a walking buddy, so he went out alone.

“I was in a square and I heard applause behind me. A group of children were applauding my presence,” he said. “I was smart enough to applaud back.”

During that tour, they were shown the Forbidden City in Beijing, the Ming dynasty tombs, and in Shanghai an afternoon performance of the ballet “The White-Haired Girl,” a Chinese story packed with Revolutionary messaging.

One of the cellists in that state ballet orchestra would later become the mother of a girl, Hai-Ye Ni, who grew up to be the Philadelphia Orchestra’s principal cellist, a position she has held since 2006. “She wasn’t even born at the time,” said Rowe.

The Philadelphia Orchestra has toured China a total of 12 times in the last 46 years, most recently last May. Most of those tours have been part of a program of “people-to-people” diplomacy, wherein the orchestra and its musicians partner with Chinese organizations for collaborative cultural and educational programs.

The Chinese reporters in the green room of the Kimmel Center asked about the current state of U.S.-China relations, described a few years ago as “strategic distrust” and has since escalated into a trade war.

What was the perspective of the orchestra with its nearly half-century relationship with China?

“What grew was a huge layer of tactical trust,” said Platt. “During this last trip there was a controversy about ‘strategic mistrust,’ but the musical organizations that trusted us, and vice-versa, they wanted to do more things.”

“The relationship between U.S. and China is a many-layered thing,” he said. “At the top you have all kinds of arguments but further down the line you have people very anxious to continue doing things together because they have done things so successfully for many years.”

The Chinese reporters in the Kimmel Center were also curious if any of the musicians have ever visited China on their own time.

Edwards, the violinist who, at 74, looks remarkably fit, chimed in.

“I like to play tennis,” he said. “So I stay at home.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.