Coronavirus unemployment benefits are high, putting workers and employers at odds

Nationally, roughly half of American workers stand to earn more in unemployment benefits than they did at their jobs before the coronavirus pandemic.

Listen 1:44

Donna Partin owns four franchises in south-central Pennsylvania of Merry Maids cleaning service. (Kate Landis/PA Post)

Are you on the front lines of the coronavirus? Help us report on the pandemic.

Donna Partin is itching to give you a hand with the housekeeping.

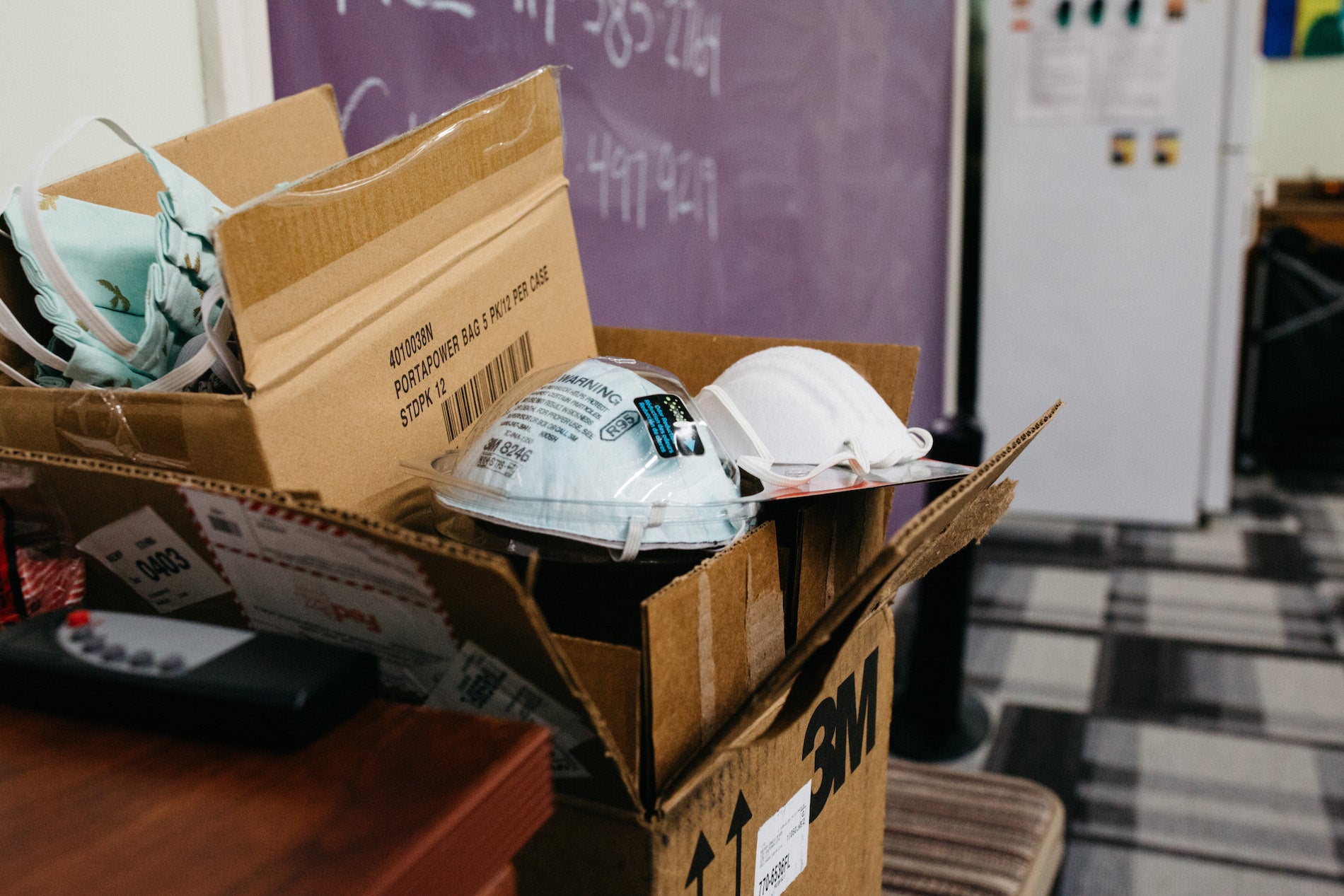

Partin, 60, is the owner of four Merry Maids residential cleaning franchises in south-central Pennsylvania. Although janitorial services were exempted from Gov. Tom Wolf’s shutdown order, Partin closed her business in mid-March because she couldn’t find enough personal protective equipment and cleaning supplies for her employees to work safely, laying off all 40 of her full-time cleaners in the process.

Now, Partin said, she’s found enough masks, gloves and supplies to clean homes safely. Clients are lining up for appointments. And Partin has received a federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan that will cover her payroll costs for the next two months.

But there’s still one big hurdle: about a dozen of her employees refuse to return to work.

“I believe that they are scared,” Partin said. “If you listen to a lot of what’s going on [on the news], it’s a lot of overkill, on the fear factor.”

Compensation is another motivation. Before the pandemic, workers in Pennsylvania were eligible to receive about half of their weekly income through unemployment. Those who apply for the benefit now receive an additional $600 a week in federal assistance through July 25 — a uniform allotment for everyone across the country no matter prior wages.

Merry Maids employees usually make about $500 a week, so total unemployment compensation pays them more than one and a half times normal.

“It’s not my employees’ fault and it’s not my fault either. It’s just that [the government] created this storm of oppositional forces,” Partin said. “It’s truly mind boggling.”

Workers tell a more nuanced story.

Some of Partin’s employees told Keystone Crossroads that their decision to not work was more due to family obligations and safety concerns than financial opportunity.

“I want to go back, believe me,” said Merry Maid cleaner Tania Goolsbee. “However there are quite a few of us employees that just feel like…we just aren’t ready.”

‘Pay them a competitive rate’

As Pennsylvania gears up for the slow process of re-opening the economy, business groups and some Republican state lawmakers warn that workers could prefer to collect boosted unemployment checks rather than return to the job.

Nationally, roughly half of American workers stand to earn more in unemployment benefits than they did at work before the coronavirus pandemic, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of federal data.

The issue is especially pressing to business owners who have received a coveted PPP loan: federal guidelines say a business must devote most of the funds to rehiring staff and covering payroll at pre-pandemic levels for the loan to be forgiven.

Here, federal assistance for both workers and small businesses has come to a head as concerns over health and safety continue to swirl.

For business owners of industries deemed essential, Gov. Wolf recently gave this advice: pay more.

“I was a business owner,” Wolf said at a press conference on April 21. “And when I wanted employees to come to work and I was concerned about any competitive rates that they might be looking at, I had to make sure that I was paying them a competitive rate.”

Partin said she has increased the wages of employees that have returned to work, but she can’t compete with unemployment. So she’s taking a different tack: If her employees don’t return to work by May 4, Partin said she plans to report to the Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry that they are refusing to work, a move that could threaten their benefits.

“It’s up to [state officials] to do whatever they want to do,” Partin said.

Partin said she believes she is legally obligated to report this information. That’s a misunderstanding. While employers are “strongly encouraged” to report employees that refuse a return to work offer, they are not required to do so, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry.

‘Catch-22’

Tania Goolsbee wants to be clear about something: deciding not to return to work as a Merry Maids cleaner was not an easy choice.

“I love my job,” said the 47-year-old York County resident. “I love all the employees. I love my manager. I honestly can’t put into words what my job means to me.”

Goolsbee said she asked her manager to be laid off a few days before Wolf’s shutdown order — a decision made easier because she relies on Medicaid, not her employer, for health care.

She was especially worried that going to work was putting her husband, who has emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, at risk. Even with her managers’ promise of more safety gear and new training, the fear hasn’t abated.

“If I were to bring [coronavirus] home to my husband, it would kill him,” she said.

Goolsbee makes about $400 a week at Merry Maids, far less than her current weekly unemployment payout of $794. But while she has been on unemployment since March, Goolsbee only began receiving her $600 bump last week. Until then, she was struggling to buy food and pay her bills on a $194 weekly payout.

Now, Goolsbee said, she has breathing room.

But drawing unemployment still makes her uncomfortable.

“I don’t like it,” she said. “I would much rather be back out in the workforce, keeping busy.”

Goolsbee plans to keep monitoring coronavirus statistics and Wolf’s press conferences to make a decision on when to return to work. It’s a frustrating situation, she said, made more uncomfortable by the perception among some that workers like her only have finances in mind.

“I feel we are just as much in a Catch-22 as our employers,” Goolsbee said.

‘Works out good for me’

Cheyenne Warner was one of the last Merry Maids employees to be laid off, stretching herself thin covering for co-workers who stopped coming to work out of concern for sick family members or to watch their children.

“I tried to stay as long as possible,” said Warner, 23, of Dover. “My manager was pretty thankful.”

Warner had no trouble signing up for unemployment. She’s now receiving about $850 a week in benefits — significantly more than she makes at her job.

“It works out good for me,” Warner said. “I still live with my parents.”

Warner told her manager last week she would not return to work. She said the decision was primarily motivated by safety concerns: Her mother has asthma, and she doesn’t want to risk bringing the virus home.

“I am worried about [losing unemployment],” Warner said. “But I would rather worry about my health, and my families’ health.”

‘No man’s land’

Usually, employees cannot decline work and continue to draw unemployment benefits, but guidelines have shifted during the pandemic.

Workers who are under quarantine, are caring for a sick family member, or are watching children out of school are eligible to retain their benefits even if their employer asks them to return to work.

Workers who refuse to return but who do not fit one of those scenarios are not eligible for unemployment, but exceptions can be made if the worker has “good cause.”

Businesses are concerned that will leave them little leverage to convince workers to give up unemployment and return to payroll, said Pennsylvania employment attorney Jeffrey Campolongo, who has been advising child care providers in the state on these issues.

“We’re in no man’s land right now,” Campolongo said. “It’s scary.”

Donna Partin of Merry Maids said she would struggle to make payments on her PPP loan if she is unable to recall her workers quickly enough to fulfill grant requirements.

“Those would be very hefty payments,” she said.

There are also workers in the inverse situation: those that, for safety or financial concerns, would prefer to be at home collecting unemployment but are working because their industries have been deemed “essential” by the state.

That’s the bind Scott Lutz is in. Lutz, 34, is a sales agent at a GoWireless store in Norristown. The business has been deemed ‘life-sustaining,’ a designation Lutz said is both unnecessary and dangerous.

“Most of the people who come into the store still are 70 or older,” Lutz said. “People are coming in because they need help, or they want to delete their text messages, or they have questions about Facebook. These are not life-sustaining issues.”

Lutz earns much of his money through commission, pulling in an average of $1,400 a month on top of his $10 an hour regular wage. But during the pandemic sales have tumbled to almost nothing. Lutz said he would make substantially more, and feel a lot safer, if he was receiving unemployment.

“It just stinks,” Lutz said. “I am not here because I am a hero. I am here because I am stuck.”

—

Ed Mahon of PA Post contributed reporting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)