Commentary: Surfers are the unsung heroes of the beach

-

-

-

-

-

-

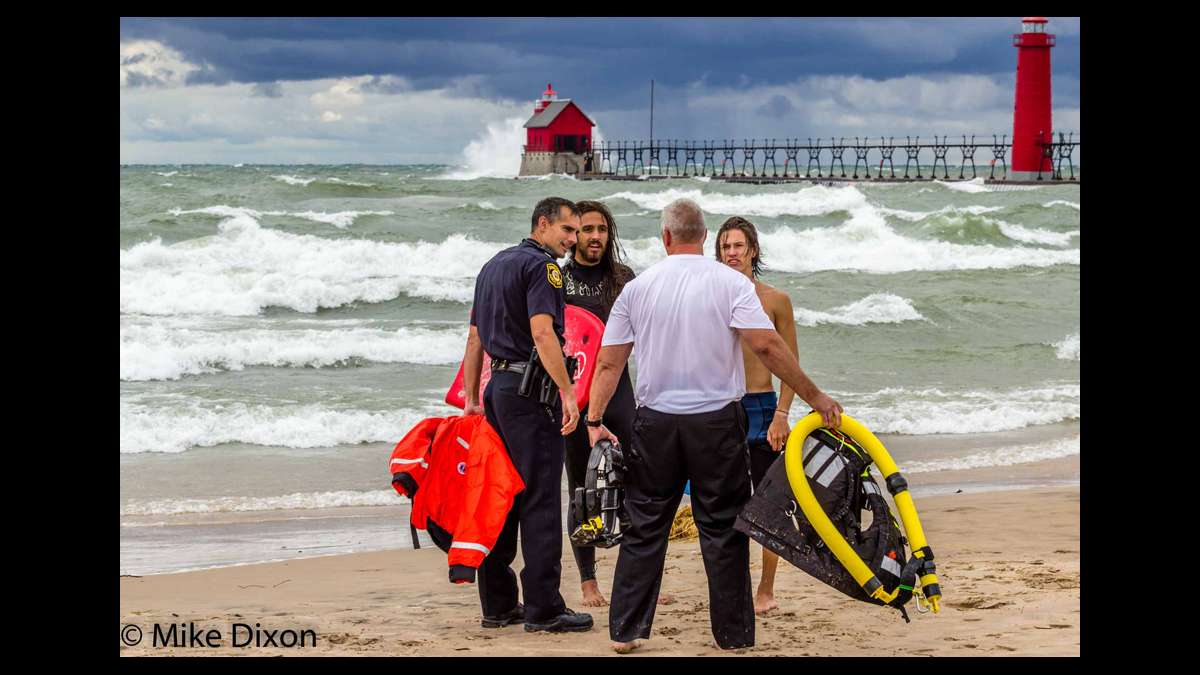

Surfer Zebulon Boeskool (3rd from left) appears exhausted after he and another man saved two distressed swimmers in Lake Michigan on Aug 20

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

I started surfing 17 years ago, armed with a bar of pink wax and a leash I secured to the wrong ankle. But even before my first paddle out, I knew a thing or two about surfers. Their reputation — bronzed hippies who assign spiritual significance to their sport and get stoned a lot — precedes them. Rarely does anyone talk about the Jersey Shore surf community comprising something else: unsanctioned protectors of an unguarded beach. Educators of newbie swimmers and water-logged boogie boarders. Lifeguards after the lifeguards go home.

I started surfing 17 years ago, armed with a bar of pink wax and a leash I secured to the wrong ankle. But even before my first paddle out, I knew a thing or two about surfers. Their reputation — bronzed hippies who assign spiritual significance to their sport and get stoned a lot — precedes them. Rarely does anyone talk about the Jersey Shore surf community comprising something else: unsanctioned protectors of an unguarded beach. Educators of newbie swimmers and water-logged boogie boarders. Lifeguards after the lifeguards go home.

We already know surfers are vocal advocates for a clean beach — the South Jersey and Jersey Shore chapters of the Surfrider Foundation run several campaigns encouraging beachgoers to leave no trace. And when people do leave litter behind, it’s often surfers who clean it up and post videos to social media encouraging others to do the same.

Saving lives

But surfers also help maintain a safe beach. Take the harrowing incident last summer where surfer Zeb Boeskool and others helped save two drowning teenage girls – one of whom wasn’t breathing – from Lake Michigan. A photographer on the beach used his lens as a spotting tool (See photos in gallery above), which helped Boeskool pinpoint the location of one victim in the seven-foot swell. Both girls made a full recovery.

While this story made national headlines, many similar rescues have flown under the radar. “Surfers pull people out of the water all the time,” said Rob Connor, Captain of the Seaside Heights Beach Patrol. “If you find yourself in trouble after hours — and we never recommend swimming after hours — it can help to flag down a surfer.”

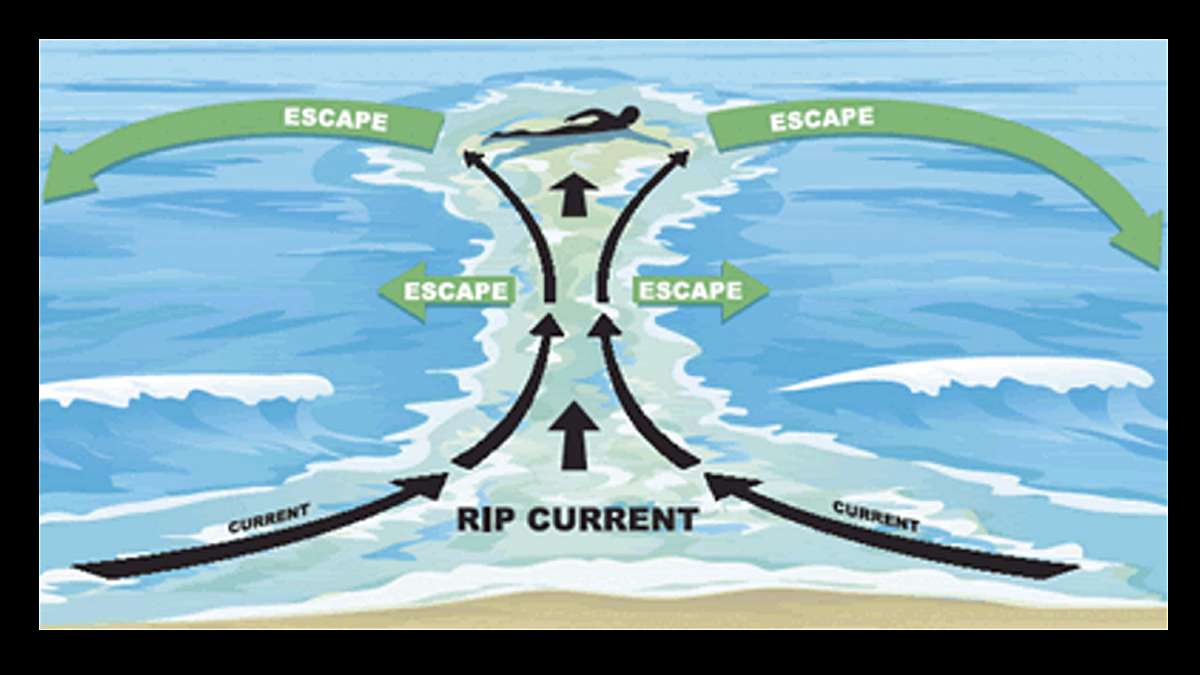

That’s largely because the rash guard-wearing set are familiar with rip currents. These narrow channels of water sweep out to sea like a river, taking unsuspecting swimmers – like the Michigan teenagers — with them.

Surfers make a special point of identifying a rip’s location, strength and size, because they can use these slipstreams for a little boost when paddling through the breakers and out to the lineup, the ideal position for catching a wave. This intimate knowledge of the flow field — and how to navigate it — allows them to quickly recognize and reach panicky swimmers caught in the channel.

Untold stories in New Jersey

Eight years ago, Cape May Court House-based painter Brian Herron rescued a fellow surfer who’d broken his neck during a hurricane swell on Broadway Beach in Cape May, where a steep slope makes for dangerous shorebreak. Brian pulled the man to safety, called an ambulance, and kept the victim calm until help arrived. As far as dramatic rescues go, this one ranks pretty high. But it’s the less sensational, rip-current related saves that occur all the time.

Eight years ago, Cape May Court House-based painter Brian Herron rescued a fellow surfer who’d broken his neck during a hurricane swell on Broadway Beach in Cape May, where a steep slope makes for dangerous shorebreak. Brian pulled the man to safety, called an ambulance, and kept the victim calm until help arrived. As far as dramatic rescues go, this one ranks pretty high. But it’s the less sensational, rip-current related saves that occur all the time.

“It happens nearly every time I surf,” Herron said. “It’ll be after 5pm, and I’ll see a little kid swimming right next to me or playing on a boogie board while his parents are back-beach and not necessarily paying attention. Ten minutes later, the kid’s way out to sea and freaking out. I’ll paddle over and tell him to stay calm so that I can coach him in. Or I’ll tell him to grab the leash of my board so that I can paddle him in.”

It’s not always children who need help.

Three years ago, marine biologist and Cape May bartender Billy Scott ran to the aid of an elderly gentleman who slipped on a patch of algae on the jetty at Cove beach, also in Cape May. Billy wrapped his shirt around the man’s broken leg in order to stop the bleeding until the on-duty lifeguards reached him.

Three years ago, marine biologist and Cape May bartender Billy Scott ran to the aid of an elderly gentleman who slipped on a patch of algae on the jetty at Cove beach, also in Cape May. Billy wrapped his shirt around the man’s broken leg in order to stop the bleeding until the on-duty lifeguards reached him.

Three years before that, at 8am on a September day, Scott came to the aid of two burly fireman who went for a swim on Wildwood’s 15th Street Beach.

“As soon as they got in the water, I turned to my buddy and said, ‘We’re going to have to save these guys,’” Scott said. “There were pretty bad rips that day. Sure enough, they ended up about 100 yards off the beach, and you could see it in their faces – they were about to go under. We paddled over, put them on our boards and pushed them in to shore. Surfers do this kind of thing all the time.”

And yet, they never ask for credit. When a local organization tried honoring Herron for his Broadway Beach rescue — the victim made a full recovery — he told them he wasn’t interested. In his mind, he didn’t do anything special. For surfers, educating swimmers, occasionally helping them out of trouble, and sharing knowledge and stoke for the water is all in a day’s work.

“It’s a matter of respect for mother ocean,” said business consultant Ed Drozda, who began surfing in South Jersey in 1965. “I don’t treat her lightly because I think she’s pretty damn tough, and I mean that in a reverent way. If I see people behaving in a fashion that suggests they don’t realize what could happen, I let them know – Hey, this is a nice place, a fun place, but she’ll snap your neck if you take her lightly.”

As for that stoner reputation?

As for that stoner reputation?

“It’s crazy this rap has hung on since the 60s,” Herron said. “It’s true that we have good vibes – that’s the lifestyle. But we’re not a bunch of hodads falling asleep on the beach with bottles of wine in hand. Especially nowadays, surfers are serious athletes. And they can be a great asset to the community.”

Special thanks to Mike Dixon Photography for allowing us to use his dramatic rescue photos

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.