Chester Springs preserves the site of the only military hospital built during the Revolutionary War

While George Washington’s army waged war against Britain, Yellow Springs Hospital fought a deadlier enemy: contagious disease.

Listen 3:39

Historian Sandra Momyer, the retired executive director and archivist at Historic Yellow Springs, sits among the ruins of an America's first military hospital. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Delco to Chesco and Montco to Bucks, what about life in Philly’s suburbs do you want WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

The Historic Yellow Springs campus in Chester Springs, Pennsylvania, has a monument to the Revolutionary War’s greatest threat.

Disease was a far greater killer than combat. An estimated 6,800 American soldiers were killed in action, but 17,000 died from afflictions including typhoid, dysentery, smallpox and the flu.

“Smallpox has made great havoc among them,” wrote Joseph Hewes, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, upon the retreat of the Continental Northern Army from Quebec.

“The Army has melted away,” he wrote in July 1776. “As if the Destroying Angel had been sent on purpose to demolish them.”

A revolution in medical standards

Sick and wounded soldiers were often cared for in ad hoc field hospitals set up in churches and private homes. But these houses of healing often became death traps of contagion.

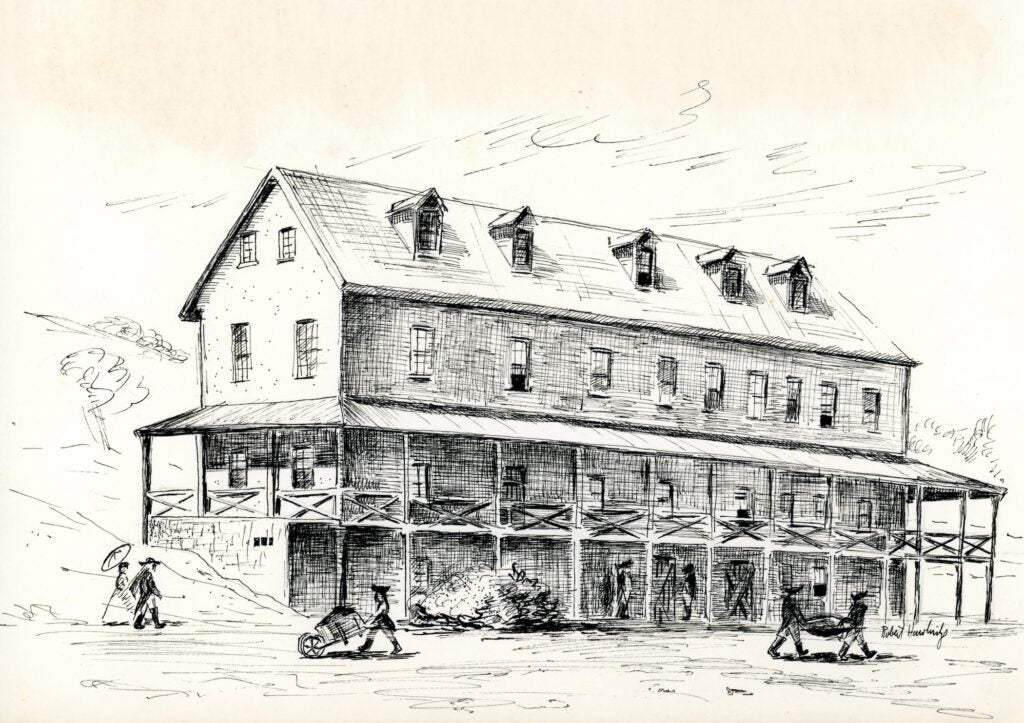

When Gen. George Washington set up a winter encampment at Valley Forge in 1777, he tried something different. He commissioned the first and only purpose-built Continental Army hospital at Yellow Springs, a few miles away.

Dr. Bodo Otto was put in charge. His approach to disease was radical at the time: cleanliness.

“Medicine was limited, and the budgets were small, but there were things that could be done,” said Chester County historian Sandra Momyer. “That meant serving hot, steamy food so bacteria wasn’t involved. It meant isolating those who were recovering from those who were newly sick. It meant clean clothing and clean bedding. Washing hands at least once a day.”

Momyer said those measures may sound obvious now.

“Those are things that seem very common-sense to us today, but they were critical,” she said. “Going into the war, they had no knowledge of medicine, they had no knowledge of how our body functioned. It was very, very primitive.”

Momyer is the retired, former director of Historic Yellow Springs, a campus of historically significant sites in Chester County dating back about 300 years. The original stone foundation of the 1777 military hospital is still there, preserved as a monument ruin.

There were other buildings used as hospitals during the war, notably in Bethlehem, Lititz and Ephrata. There, the Continental Army usually took over existing buildings, such as barns and churches. Disease ravaged not only those field hospitals but the communities surrounding them as well.

At a hospital in Bethlehem, for example, five soldiers died on the same straw bedding before it was changed, despite suffering from relatively minor ailments, according to a 1964 historical journal.

“When Washington took over the colonial army in 1775, he really had no precedent to go by. There was no knowledge,” Momyer said. “Of the 1,200 doctors that served in the Revolutionary War, only 400 of them had professional training.”

Under Otto’s leadership, the hospital at Yellow Springs separated sick patients from those who were uninfected, incinerated the clothes of dead soldiers rather than allow others to reclaim them, and cleaned bedpans regularly. An extensive herbal garden was planted at the site to make healing tinctures that were distributed to other hospitals in the army system.

Medical knowledge advanced at Yellow Springs by leaps and bounds.

“A lot of medicine that we know today, even in our modern medicine, occurred from military battles,” Momyer said. “When you’re in the field, decisions have to be made in a snap. Doctors discover things when they’re forced to make these rash decisions. That’s what happened here.”

A new professionalism among doctors emerges

Washington was deeply concerned about the health of his soldiers, worried his forces would “smoulder away with sickness” if high-quality medical care was not available everywhere, and quickly.

In a letter to the Continental Congress in February 1777, Washington proposed a system of military hospitals and a network of doctors throughout the colonies, and he urged that those doctors be well paid.

“In determining the sum that is to be allowed to each, you ought to consider that it should be such as will induce gentlemen of character and skill in the profession to step forth, And in some manner be adequate to the practice which they leave at home,” he wrote.

Congress approved a national military medical program with generous pay for doctors, but as the new nation was notoriously short on cash, few doctors were actually paid during the war. When Otto resigned his commission in 1781, Congress issued him a certificate of indebtedness for over $2,000.

For many doctors, money was not the real prize.

“The Revolution is a big moment for the physicians of the early United States because it is their moment to prove themselves as an independent profession,” said Meg Roberts, a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Edinburgh who studies caregiving during the Revolutionary War.

“The revolution was a perfectly timed moment for them to found the nation’s medical hierarchy,” she said.

Women barred from medicine and wiped out of the historical record

The establishment of that medical hierarchy was not smooth. Letters of the period reveal plenty of infighting and discrediting among doctors who wanted to climb the ladder.

Roberts says this newly standardized medical system did not welcome women in its ranks. In Colonial America, women were commonly recognized as healers, ran apothecary businesses, and were sought out to care for neighbors who fell ill. But when the Continental Army began professionalizing military medical care, women were left out.

Roberts is the consulting curator of a new exhibition, “Nursing the Revolution,” at the Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing at the University of Pennsylvania. Opening Jan. 14, it shows the role of nurses in the Revolutionary War. On Feb. 18, Roberts will lecture during a related symposium at Penn about women’s Colonial-era medical practices.

“Women’s expertise was part of the way medical practice occurred in the Colonial period,” Roberts said. “The Revolution, because it is a nation-building moment, reifies a lot of the physicians’ authority over medicine in a way that excludes women.”

The nursing work at the Yellow Springs hospital was done by women, largely recruited from surrounding farms. They were not “nurses,” per se, as that title did not exist at the time, but rather caregivers without formal training, relying on skills developed as wives, mothers and housekeepers.

But the historical record of those women is sparse.

“They’re extremely absent,” Roberts said. “There’s no contemporary evidence for their work as nurses at all.

One Revolutionary nurse still stands out

One name that survived is Abigail Hartman Rice, a German-born wife of local miller Zachariah Rice and sister to Continental Army officer Maj. Peter Hartman, who commanded Pennsylvania battalions.

Much of Rice’s adult life was spent pregnant: She gave birth to 21 children before she died at age 47. Nevertheless, she is known to have volunteered some of her time at the Yellow Springs hospital, likely feeding and washing patients.

“Her brother was doing so much to help the war effort, I think she wanted to help the war effort. This was the way women could do that,” said Momyer. “I feel she was a woman of a good heart and wanted to do the right thing.”

The fact that Rice was a German immigrant may have also played a part in her decision to help the war effort.

“There was a lot of pressure on German communities to show their support for the war,” Roberts said. “That specific small community in Chester Springs, they were pretty convinced by the idea of the American nation. They wanted to prove that they were part of it.”

Ultimately, Rice became a martyr for the American cause. She contracted typhus while tending to the sick at Yellow Springs, which ultimately killed her in 1789.

She is one of the very few Yellow Springs nurses known by name, largely because her descendants insisted on it. There is a sizable trove of research done by the Hartman-Rice family to memorialize their ancestor as a patriot.

There used to be a chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution named after Rice, until the organization rescinded her name in the 1990s because there is no paper trail that definitively ties her to the war effort.

“Oral history tradition as it passes down through generations is considered valid proof, but evidently the Daughters of the American Revolution aren’t ready to accept that,” Momyer said. “But all of us are going to keep pushing for our hero Abigail.”

As a historian, Roberts said Rice is more interesting for the way she is memorialized than for the little we know about her life.

“In the 1870s, ’80s and ’90s there’s a lot of immigration to the U.S., so there’s this extra need to prove your family goes back and contributed to the Revolution. It was a real status symbol,” Roberts said. “Societies were founded to prove certain people in the U.S. were members of the in-group from the beginning. Suddenly everyone wants to be related to a Revolutionary War nurse.”

A plaque bearing Abigail Hartman Rice’s name is in the bell tower of the Washington Memorial Chapel in Valley Forge National Historic Park. Her gravestone is in the cemetery of Saint Peter’s Pikeland United Church of Christ in Chester Springs.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.