Can we call it a comeback for Philly Catholic schools?

ListenFive years ago, Catholic education in Philadelphia was on life support. Since then, an independent nonprofit has saved 15 schools in low-income neighborhoods. Could it be the beginning of a comeback?

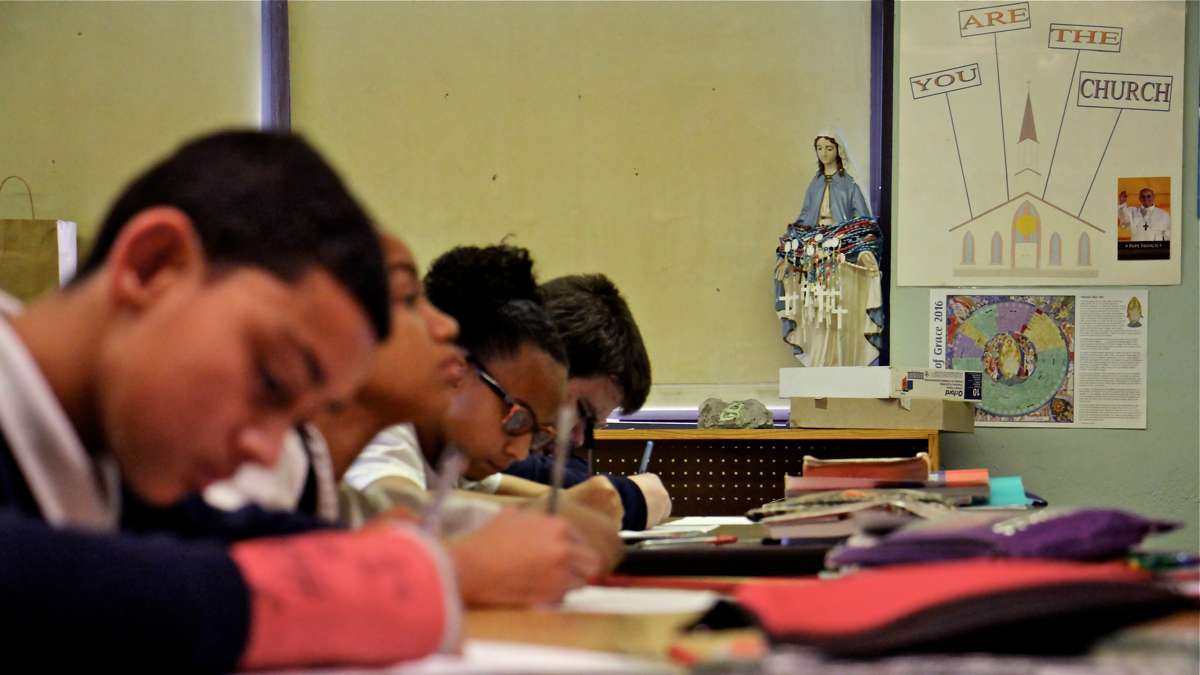

One of the first things you notice when you walk the halls of St. Gabriel school in the Grays Ferry section of South Philadelphia is the sound. Or rather the absence of it.

A lone teacher’s voice drifting out an open door. The sound of someone’s shoes clacking along corridors. The still gaze of a religious statuette perched in the corner.

Catholic schools tend to be quiet, orderly places. That’s part of the appeal.

But all that carefully orchestrated tranquility evaporated on a winter day in 2012.

“I could just remember we heard shouts throughout the whole school,” says long-time teacher Elaine Carboni. “I’ve never heard a shout as loud.”

About a month earlier, the Archdiocese of Philadelphia released a Blue Ribbon Commission report on Catholic education in the city that read more like a eulogy. It called for 48 area Catholic schools to close, among them 104-year-old St. Gabriel. It was a rock-bottom moment for Catholic education in the city. But it would birth one of Philadelphia’s most interesting education experiments.

Shortly after the closures were announced, 14 schools broke off from the Archdiocese and formed their own network of urban Catholic Schools. They named this coalition the Independence Mission Schools, or IMS. On that boisterous winter day in 2012, St. Gabriel had become a charter member.

“We couldn’t control the students,” Carboni recalls. “At that point we said let them revel in their victory.”

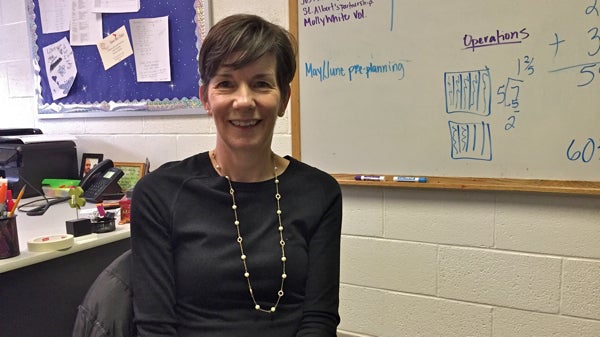

Elaine Carboni teaches eighth grade at St. Gabriel School in South Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Elaine Carboni teaches eighth grade at St. Gabriel School in South Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The joy pulsing through St. Gabriel was a kind of cathartic relief, built up over decades. For the past 60 years, Catholic schools around the country had been bleeding enrollment and money — nowhere more so than the industrial Northeast.

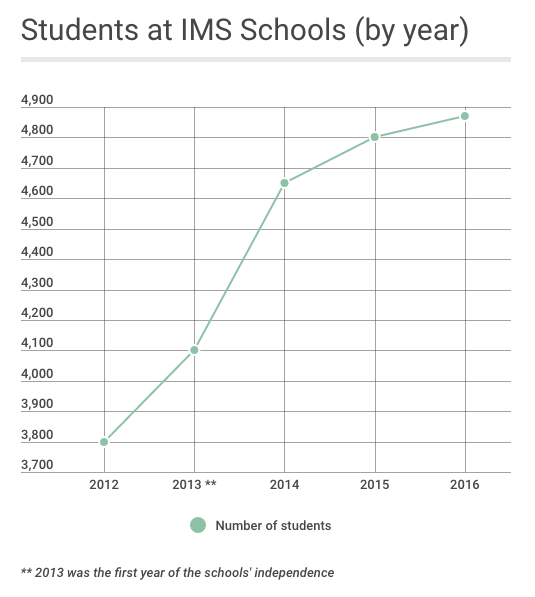

IMS began in 2012 under the seemingly fantastical notion that, with a bit of effort and business savvy, motivated lay people could save 14 schools on the brink of failure. Fast forward five years, IMS has added a 15th school and grown enrollment by nearly 30 percent.

Now, as the national political winds howl in the direction of school choice, a movement once bent on preserving civic institutions might become something more: a vehicle for growth. Five years after one of its darkest days, could Catholic education make a comeback in the city of Philadelphia?

Before we explore that question, a bit of history.

The rise and fall of Catholic education

You can find traces of Catholic education in Philadelphia dating to the late 17th century, but a system of parochial schools didn’t form until the middle of the 19th century.

By then, religious education in public schools had become a source of increasing tension. The swelling ranks of immigrant Catholics objected to required classroom readings from the King James version of the Bible. In 1844, a Catholic school principal in Kensington suggested a temporary suspension of Bible study. His proposal set off a months-long chain of destruction that would become known as the “Bible Riots.” From the ashes of this episode — perhaps the most intense spasm of anti-Immigrant violence in the city’s history — Catholic education would be born.

Convinced that the city’s Catholic children were no longer welcome or safe in government-sponsored schools, Bishop John Neumann established a central Catholic school board in 1852 and pushed local parishes to found their own schools.

“You have in the 1840s, 50s and 60s this deliberative movement to form a parallel system that — because it couldn’t be funded by the government —would be funded by the Catholic community,” said Richard Jacobs, professor at Villanova University and scholar on the local parochial school system.

The basic structure of this system would look much like its government-run counterpart. Parochial schools would be free to parishioners and have their own catchment areas. Neighborhood Catholics would follow well-trod feeder patterns up through the grades, with little emphasis on outreach or competition.

“I mean everybody went. It was a no-brainer,” said Marie Keith, the marketing and enrollment director at IMS. “You went to your Catholic school around the corner and then you went to the high school that fed into that.”

For decades, thanks to demographic growth of Catholics and feeling unwelcome in public classrooms, simply existing alongside the public system was enough to ensure growth. At its high water mark in 1959, there were 271,000 students in schools run by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. Six years later, national Catholic school enrollment peaked at an astounding 5.6 million.

Sister Santa Teresa teaches a third-grade class at Saint Gabriel School. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Sister Santa Teresa teaches a third-grade class at Saint Gabriel School. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

But this final spurt of growth, made possible by the baby boom, masked underlying problems.

For starters, Catholics were scurrying to the suburbs. Once there they found high quality public schools where they felt accepted. As Irish, Italians, and others were folded into the blanket whiteness of suburbia, there was less need for a sheltered school system.

Labor costs were also on the rise. For decades, a steady supply of priests and nuns had made it disproportionately cheap to staff parish schools. That pipeline, however, was drying up.

“As a result lay people increasingly became the system’s source of teachers,” says Jacobs. “But that required paying a more just salary than what you could pay to the sisters and brothers and priests who taught in the school.”

By the 1970s, Catholic schools in Philadelphia began to charge tuition, according to Jacobs, but that alone wasn’t enough to keep the system in the black. Between 1964 and 2012, the Archdiocese of Philadelphia closed 132 schools and merged another seven.

“The Catholic schools were set up in a model that served the past and not the present. They served a church-going population that was supporting a vibrant parish financially and the parish was supporting the school.” said Anne McGoldrick, current IMS president and its founding chief financial officer. “The model was just on a collision course.”

In the inner city, some Catholic schools survived by serving non-Catholic families who sought an alternative to the city’s crumbling public schools. But that strategy would provide only temporary relief.

By the late 1990s, charter schools had sprouted in large cities across the country. Subsidized by taxpayer dollars, the charters had a key market advantage over parish schools — they were free. Decades of decline turned into an outright free fall. By the end of the millennium’s first decade, many urban Catholic schools found themselves on the edge of insolvency.

“It was constant worry,” said Carboni, who began teaching at Catholic schools in 1975. “Are we next? Are we next to go?”

“Merging a bunch of failing businesses”

One of those schools mired in existential crisis was St. Martin de Porres at 23rd and Lehigh — a Dick Allen long toss from where Connie Mack stadium once stood. St. Martin de Porres was “on the dole,” an inside-baseball term that meant the school’s operations were being subsidized by the archdiocese. The long-term prognosis was grim.

In 2010, a group of wealthy and well-connected lay people offered to unburden the archdiocese. They would oversee the school as an independent nonprofit provided the Archdiocese could lease them the facilities for a nominal fee. The church agreed, and the lay board quickly proved adept at raising money for the beleaguered school.

About a month before the Archdiocese released its 2012 Blue Ribbon Commission report, three representatives from the St. Martin de Porres board approached the church about expansion plans. The impending report would lay bare what many already knew: The church could no longer afford to bankroll many of the city’s Catholic schools.

The crew from St. Martin de Porres believed it could save some of these schools by binding them together in an independent network. They figured with a new governance structure and some entrepreneurial spunk they could do for these schools what the overburdened Archdiocese could not.

“We took best business practices, the same thing we do with our businesses,” said Michael Young, an IMS board member and local property manager. “You’ve got an old bureaucracy that’s been set in their way of doing things for so long that they weren’t able to think outside the box.”

This philosophy should be familiar to anyone who has followed the school choice debate. An old, sclerotic monopoly stumbles. A small, nimble outsider tries to swoops in and do the job better.

About a month after the Blue Ribbon Commission report went live — and about two months after negotiations had begun — 14 diocesan schools learned they would become part of IMS.

Beginning in 2013, the Archdiocese relinquished full control of the mission schools. IMS incorporated as its own nonprofit with its own central staff to provide back-office supports such as enrollment and human resources management. (IMS schools also share some support staff such as counselors and development officers.)

As its parting gift, the Archdiocese granted one-dollar leases to each of the 14 schools and provided roughly $1.5 million in start-up costs spread over the first two years. From there, the IMS schools were on their own.

At the time, the 14 schools were operating at a combined annual deficit of roughly two million dollars, says Brian McElwee, the board chair at IMS. Even with the attention-grabbing governance shift, urban Catholic schools were still a product few wanted or could afford.

“Merging a bunch of failing businesses is usually not a recipe for success,” he says.

Starting with the secretaries

There are a lot of potential explanations for what happened next. But if you want the most succinct synopsis of how IMS was able to save, and even grow, a collection of troubled schools the best place to start is at the front desk.

At any school, the secretary who sits at the front desk does just about everything outside the realm of direct instruction: dispense Band-aids, comfort upset students, corral upset parents, etc. At Catholic schools, the job also requires doling out applications.

“Someone would walk in the office and say can I have an application and they would reach in their drawer and they would hand them a paper application and say, y’know, bring it back,” said Keith, the IMS enrollment and marketing chief. “And that was first big red flag.”

The way Keith saw it, there was also a problem with the way the secretaries answered the phone. Whenever someone would call asking about enrollment, the secretaries would tell them how much the school cost. Seems reasonable, but to Keith it wasn’t refined enough. They needed talking points.

“The staff person would say it’s $4,000 and of course the person’s going to hang the phone up,” said Keith. “And I retrained them to say our stated tuition is four thousand however our families pay according to need.”

(A number of diocesan schools now broach the topic of tuition in a similarly measured way, according to Christopher Mominey, the archdiocese’s secretary of education.)

This retraining of secretaries may sound marginal, but it was emblematic of the changes IMS staffers wanted to make at every level of the network. They wanted to bring some semblance of standardization to small parish schools that had acted largely in isolation — some for over a century.

When IMS took over the 14 schools, tuition fluctuated wildly and methods for distributing financial aid often had no apparent logic. IMS instituted a financial aid scheme modeled off college aid formulas. Families would tell a school their income and the school would tell them how much they’d be expected to pay based on a predetermined formula. IMS declined to release the formula, though they noted that the average family pays just over $2,000 a year.

Raising tuition to lower cost

Since most of the IMS schools are located in poor, urban neighborhoods the network’s leaders knew they needed to lower the price point so they could get more families in the door.

And to lower the price point they did something that would only work in the funky world of school funding–they raised tuition.

This is where our story veers off into the weeds, but you’ll want to follow along.

Pennsylvania has two education tax credit programs, the Educational Improvement Tax Credit (EITC) program and the Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit (OSTC) program. Essentially these programs allow businesses to divert money that would have gone to state taxes and sink them into scholarship programs for students who want to attend private school.

It’s basically vouchers lite, and IMS relies heavily on this government support. In a stroke of good fortune, the OSTC program, which is designed to aid students who would otherwise attend low-performing public schools, was passed the year before IMS launched.

By 2015, scholarship money made up nearly 30 percent of IMS revenue at $6.1 million.

Through the state’s tax credit programs, a company can cover a child’s tuition at a private school up to $8,500. And this set-up provides an odd incentive for low-cost schools to increase the list price.

Think of it like this: If a school only costs $1,000, a company can only give it $1,000 per student in tax credits. Maybe that’s fine if the actual cost of educating students is $1,000 a head. But IMS determined that its actual costs were somewhere in the neighborhood $5,500 per student.

And so as one of its earliest acts, IMS raised tuition — first to $4,000 and then to $4,500.

“I would be less than honest if I didn’t tell you I had many sleepless nights that first year wondering if we were gonna pull it off,” says McGoldrick, then the network’s CFO. “Because sometimes all people see..is that tuition number.”

Anne McGoldrick, president of Independent Mission Schools. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Anne McGoldrick, president of Independent Mission Schools. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Today, according to McGoldrick, tax-credit scholarships make up about 35 percent of IMS’s total intake. Another 15 percent comes from private philanthropy and roughly half comes from families.

“We live in Pennsylvania where we have the benefit of the tax credit programs that enable people to fund scholarships,” says McGoldrick. “And our model in Catholic schools prior to IMS was not taking advantage of that program.”

McGoldrick comes out of the financial world. Prior to starting at IMS, she worked at a global investment firm. For too long, McGoldrick says, Catholic schools were starving themselves to keep tuition low rather than acknowledge the fact that they were “running in a scholarship market.” Capturing those dollars — the government-enabled dollars — as vital.

“They were operating on an age-old formula that was keep tuition as low as possible so families can afford it when in fact what you really needed to do was step back and say what are my costs, how would I fund tuition that met those costs so that I can be a viable entity and how would I get there,” she said.

IMS was formally unveiled in 2012, but it didn’t start functioning as an independent nonprofit until January 2013.

In 2012, the last year the schools were under diocesan control, they educated 3,800 students. At the beginning of the 2016-17 school year, there were 4,869 students in the IMS network.

(It should be noted that the addition of a 15th school brought 200 new students into the IMS coalition.)

‘I was just looking for an alternative’

Some of those new families were imports from the charter sector that had so decimated the Catholic schools.

Take Crystal Jackson, a mother of three from the Olney section of North Philadelphia. Jackson belongs to the subset of parents who simply don’t consider traditional public schools an option. Philadelphia has thousands of these parents, and they are prime customers for charters, catholics, and other non-public alternatives.

For Jackson, it was her own turbulent experience at Martin Luther King Jr. High School in Germantown that convinced her to keep her two oldest boys out of the public system. For years she sent them to charter schools, but soon grew frustrated with what she considered a lack of rigor.

“It’s not so much that I was seeking a Catholic school at the time,” recalled Jackson. “I was just looking for an alternative.”

During a lunch break one day in 2012 a coworker mentioned she’d seen a news report on IMS.

“I was like I never heard of that,” she said. “So I went online. I did more research and I was like I’m kind of liking what’s going on here.”

The next year, she sent her boys to Holy Cross School in Mt. Airy. Her oldest graduated last year and now attends Roman Catholic High School in Center City. The other, an eighth grader, just earned acceptance to St. Joseph’s Prep.

Like Jackson, 76 percent of IMS families are black. About 80 percent are non-Catholic. Roughly half live on incomes of $50,000 or less.

Courting non-Catholic families is baked into the IMS modus operandi. Certainly many urban Catholic schools were relying on non-Catholic families in the year prior to IMS, but IMS is different at least in the sense that it exists, at its core, to serve this population.

By boosting enrollment, IMS has been able to reinvest in some of its schools and become a more attractive magnet for outside philanthropy.

Charters with a splash of holy water

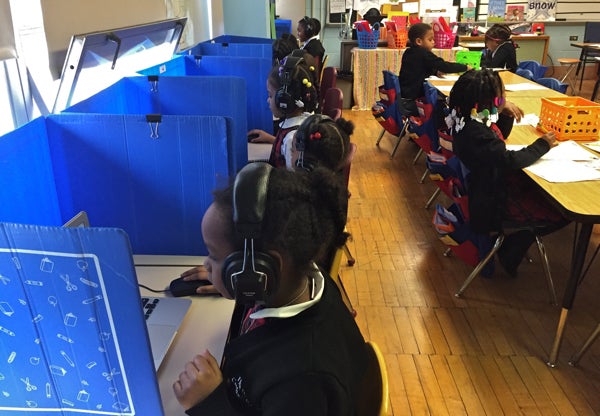

DePaul School in Germantown has received support from the Philadelphia School Partnership and Seton Partners, a group out of New York that supports Catholic schools across the country. Thanks in part to these contributions, DePaul has adopted a blended learning model where much of the work happens on school-provided laptops. A typical kindergarten class looks like something you’d find in an innovative charter or district school — small children working small, rotating groups with technology never more than a finger-tip away. It is about as far pedagogically from the nun at the chalkboard as you can get.

Now IMS doesn’t mandate blended learning and schools are still largely independent in their instructional choices. On the whole, though, there is an openness to experimentation that matches the entrepreneurial spirit behind IMS.

The hallway at DePaul school, Germantown. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

The hallway at DePaul school, Germantown. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

You can find hallmarks Catholic education at DePaul: uniforms, religion class, daily prayers. But you’re as likely to see a poster of MLK in the hallway as you are a saint. In many ways it feels like a charter school with a splash of holy water.

IMS isn’t the only network doing this kind of work. Though the exact governance models vary, there are coalitions of independent or quasi-independent Catholic schools now in Memphis, New York, Camden, and elsewhere. Cristo Rey, a chain of independent Catholic high school, has locations across the country.

The ‘most exciting education reform story’ in America?

Beyond just the parochial realm, there’s a burgeoning movement of what some school choice scholars have dubbed “Private School Management Organizations.” These are chains of private schools under a common non-profit umbrella, and they’re seen as potential vehicles for private school growth.

Philadelphia alone has both IMS and Faith in the Future, a management company that runs 21 diocesan schools across the region. Faith in the Future’s CEO, Samuel Casey Carter, is a fixture in the school choice community who penned one of the early texts on “no excuses” education reform.

“What is happening in Catholic schools across the country, but what is happening in the city of Philadelphia in particular, is the most exciting education reform story in the country,” said Carter.

The story could get more intriguing thanks to the political developments of the past year.

The new U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos has long endorsed school vouchers and tax credits as a means of expanding school choice. And though President Donald Trump’s vow to create a $20 billion federal school voucher program may be fantastical, it seems likely DeVos will be a powerful advocate for steering more public dollars to more private schools.

Here in Pennsylvania, there’s pending legislation to increase the cap on tax credits. If House Bill 250 were to become law, the total pool of available EITC dollars would go from $125 million to $175 million. The OSTC cap would go from $50 million to $75 million.

House Speaker Mike Turzai is an outspoken supporter of educational tax credits. And although Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf isn’t a fan of expanding the program, he has allowed the caps to go up in the past.

As school choice moves further into the educational mainstream, education reformers in the private sector see a golden opportunity to build off the momentum created by charters to capture more public money.

“Charter schools have made the water safe again for private school choice,” said Carter of Faith in the Future. “And now what Catholic schools all across the country are proving is that you can manage them centrally so what you get is you get the benefits of all the lessons learned from the charter school movement.”

Internally at IMS there are already aggressive expansion benchmarks.

One of the IMS schools, St. Malachy, recently bought and moved into a shuttered public school with a 500-student capacity. DePaul in Germantown purchased the shuttered parish church next door and plans to convert it into an annex. There’s also chatter of founding a new school or bringing others into the network.

System-wide, the IMS board thinks total student enrollment could go from 4,800 to 7,500 in the next three-to-five years, says founding board member Michael Young. Some on the board, he says, foresee an even steeper growth curve.

The Archdiocese serves 11,800 students in its Philadelphia-based K-8 schools. If IMS grows at the rate anticipated, it could educate as many young children in the city of Philadelphia as the once-dominant Archdiocese in one decade’s time.

Naturally, much of it will be dependent on whether more public money becomes available.

“Increased access to government funding would be very important to us and would be a game changer,” said McGoldrick. “So we would welcome that.

But do they work?

It’s probably sinful we’ve gotten this deep into an education story without mentioning academic quality.

There is general research — some of it dating back 35 years — that suggests Catholic schools do a better job than public schools educating students, and that the benefits are especially pronounced among minority students.

A blended learning classroom at DePaul school in Germantown. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

A blended learning classroom at DePaul school in Germantown. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

But on a school-by-school basis it is difficult to judge the merits of Catholic schools. IMS schools administer a nationally normed standardized test called the TerraNova, but scores aren’t publicly released. A school comparison website run by the Philadelphia School Partnership provides some benchmarks for how individual Catholic schools compare to nearby public schools, but it’s a blunt instrument.

Even if IMS test scores were public, it would be difficult to draw apples-to-apples comparisons. The subset of families who can afford even a modest Catholic school tuition are likely to be wealthier and more involved than the average family with young children in a poor city like Philadelphia.

(A parent at Holy Cross School casually mentioned that she picked the school because it didn’t have kids with absentee parents.)

“Undoubtedly children who have someone in their life who is advocating for them enough to do the process to get into an admissions school are better off than a lot of other children who don’t have that in their lives,” said McGoldrick. “It’s indisputable.”

IMS schools, like all private schools, also aren’t required to serve special education students.

IMS school inevitably educate some students who require extra academic support and may well be classified special education if they were in the public school system. But IMS admits, it does not have the capacity or special funding to take on students with severe cognitive or behavioral impairments.

Catholic schools in general have a reputation among public school advocates of being exclusionary and unwilling to take on the toughest cases.

“They don’t know what to do with kids that are suffering from trauma and are acting out,” said Donna Cooper, head of Public Citizens for Children and Youth. “They historically have expelled those kids.”

IMS has a yearly student turnover rate around 20 percent, McGoldrick says. The network hopes to lower that figure to around 12 or 15 percent.

Bigger picture, skeptics of vouchers and tax credits argue that schools like those in the IMS network siphon money from the state’s general fund, ultimately handcuffing the Commonwealth’s ability to support traditional public schools. They also point out that there’s no data on which families use tax-credit scholarships and whether they deliver any educational benefits.

“It’s incredibly difficult to track that these schools and tax credits are going to the students that need them most,” said Deborah Gordon Klehr, who runs the Education Law Center.

Critics also note that Catholic schools, IMS included, pay teachers much less than their public counterparts. Most IMS teachers make less than $40,000 a year, says McGoldrick. A first-year teacher in a Philadelphia public school takes in at least $45,000 annually.

But even those predisposed to skepticism see something noble in IMS. The schools are located in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods and they serve an undeniably needy population. Cooper says IMS schools are trying to serve minority, non-Catholic communities with a sort of ferocity and commitment to inclusion the Archdiocese never had.

“I think Anne McGoldrick is an incredible human being and if anybody could breathe life into Catholic education in Philadelphia she’s the one to do it,” said Cooper.

McGoldrick will leave IMS at the end of 2017. Her departure comes at what she calls a “large moment” for the organization and Catholic education in general.

For the first time in decades there’s evidence that Catholic schools in poor, non-Catholic neighborhoods have a future. And there’s further evidence that the government wants to fuel their growth.

No one thinks Catholic education in Philadelphia will return to its former glory. But with the right mix of management, support, and momentum it could become what McGoldrick calls a “piece” of the education reform pie.

“We have certainly focused exclusively on this point on keeping existing schools open,” she said. “But I think our view of the world, our foundation and our approach, is not limited to that.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that St. Gabriel School is in the Point Breeze section of South Philadelphia. It is in Grays Ferry. The article has been updated to reflect this change.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.