Can we make purchasing classroom tech more like buying a car?

Schools nationwide are spending over $13 billion in K-12 alone and have little idea if any of it works. We can’t afford to spend this kind of money blindly.

-

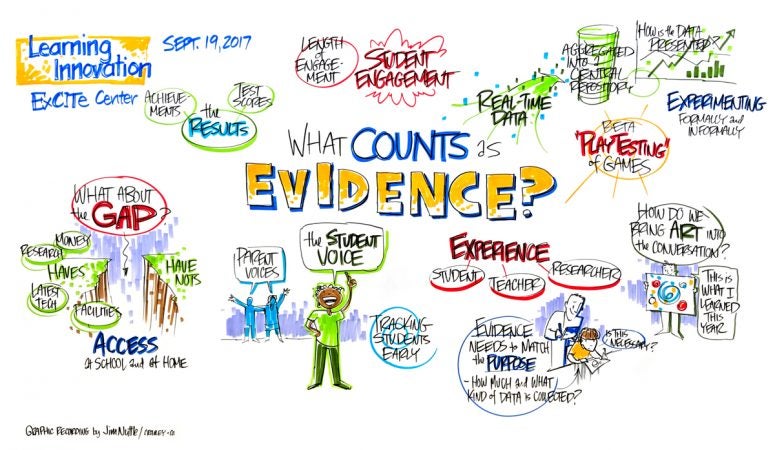

Katrina Stevens spoke about better ways of using evidence to evaluate education technology, and sharing that knowledge across the education ecosystem. (Jim Nuttle/Crowleey & Co.)

-

Katrina Stevens spoke about better ways of using evidence to evaluate education technology, and sharing that knowledge across the education ecosystem. (Jim Nuttle/Crowleey & Co.)

Right now teachers in classrooms across this country are introducing new technology into their classrooms. Everywhere. Thousands of teachers. By the end of the year, each of these teachers will be an expert on that particular tool and how to best implement it in her classroom. And hardly anyone else will benefit from this knowledge and expertise. What if we were able to harness the knowledge and expertise of individual educators to benefit the larger ecosystem?

My visit in September to Drexel University’s ExCITe Center was a welcome opportunity to share how we can better use evidence to make decisions about identifying, implementing, and evaluating education technology. The current system is broken. Schools nationwide are spending over $13 billion in K-12 alone and have little idea if any of it works and in what context. In a financial climate where funding for schools is shrinking, we can’t afford to spend this kind of money blindly.

Creating well-informed consumers

Imagine for a minute that you want to buy a new car. To make a decision, you don’t have to depend solely on what a salesperson says or on their marketing materials.

You might look at the latest Consumer Reports and other reliable sources. You get to decide if you’re willing to try a brand-new model because of the promise of the new features, knowing there could be glitches, or you could go with a reliable, time-tested model. You’re more likely to look first at cars your friends and family have liked of course, but it’s not the only factor you’ll consider.

It will matter to you if the car has been tested on road conditions similar to what you will encounter. You don’t just want to know how it drives on a perfect track. Does it drive well in snow? How will it handle the dirt road you take every day to get to work? And you’ll want to take it for a test drive to see how comfortable the vehicle is for you. Does the car still work well for a really tall or short driver? Individual fit matters.

Identifying, purchasing, and implementing ed tech should have similar supports for decision making. We need the equivalent of stickers that show gas mileage and long-term costs for maintenance. While there’s value in finding out what’s most popular and asking our colleagues what they’re using, we need more information about what is likely to work in our particular circumstances.

What efforts are currently underway?

This past April the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education, Digital Promise, and the Jefferson Education Accelerator convened 275 stakeholders in Washington, D.C., from across the educational ecosystem for the first annual EdTech Academic Research Symposium. In the previous six months, 10 working groups consisting of approximately 150 people investigated the challenges and opportunities associated with improving the use of evidence. We examined how ed tech decisions are made in K-12 and higher education, what philanthropy can do to encourage more evidence-based decision-making, and what is needed to make a focus on efficacy and transparency of outcomes central to how ed tech companies operate.

In addition to the issues raised above, several other key points arose:

Everyone wants research and implementation analysis done, but nobody wants to pay more for it.

There’s growing consensus that we should be making decisions based on merit and fit rather than marketing, but most everyone thinks it’s somebody else’s job to make that happen. Organizations that make high-quality products are frustrated that they can’t compete with companies that can afford flashy marketing. Researchers feel their work is often underutilized and rarely incorporated into products and implementations. Investors don’t often screen ed tech tools for efficacy because research doesn’t currently drive market growth. Educators are overwhelmed by the sheer number of options available and frustrated by the lack of time, professional support, and decision making tools available.

While across the U.S. we’re collectively spending millions of dollars and hours on particular products, the individual price tag for each district isn’t enough to warrant an expensive research study. Essentially we have a collective action problem.

It’s not just about what works: It’s about what works for whom in what context.

Fit matters significantly. What works in one classroom setting well may fail miserably in another. A system that accounts for matching similar circumstances and providing factors for implementation success will support educators better than one focused strictly on perfect settings.

We need to know how ed tech tools work in real-world classrooms, not just in lab settings.

Classrooms are already laboratories. We just don’t think about them this way. When I was a teacher, I hypothesized that my students would learn material if I shared it in a particular format, then I tried it. If it didn’t work for all of my students, then I tried different methods. The next time I taught the same material, I’d incorporate these successful approaches. I didn’t think about this as experimenting, but it was. We have thousands of experts experimenting and learning in classrooms every day, but we don’t have an efficient system for capturing what these educators are learning. What we want to know is what what works well in particular real-world contexts with all of the messiness inherent in education.

We need a continuum of evidence that matches need and purpose.

The level of evidence required to make an ed tech decision should match the need and risk. Not every decision requires the same level of evidence. A teacher trying an app for a few class periods may only need recommendations from trusted colleagues. However if a district is rolling out a comprehensive program across several grade levels, they should collect more rigorous evidence of effectiveness in similar settings.

Districts and companies need support to gather the right level of evidence.

We have a long way to go to provide the full support that schools need, but several organizations have begun creating resources to help: This guide by Mathematica helps educators identify and evaluate a range of evidence, as does Digital Promise’s Evaluating the Results tool. Lea(R)n’s Framework for Rapid EdTech Evaluation similarly highlights the hierarchy of rigor in different research approaches. Tools such as the Ed Tech Rapid Cycle Evaluation Coach, LearnPlatform, Edustar, the Ed-Tech Pilot Framework, and the Learning Assembly Toolkit provide useful support in conducting evaluations of the use of technology.

—

Katrina Stevens is the former deputy director of the Office of Educational Technology at the U.S. Department of Education.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.