Black folk artist Elijah Pierce is Barnes Foundation’s first new show during pandemic

A show of over 100 works takes a fresh look at the mid-century Black folk artist.

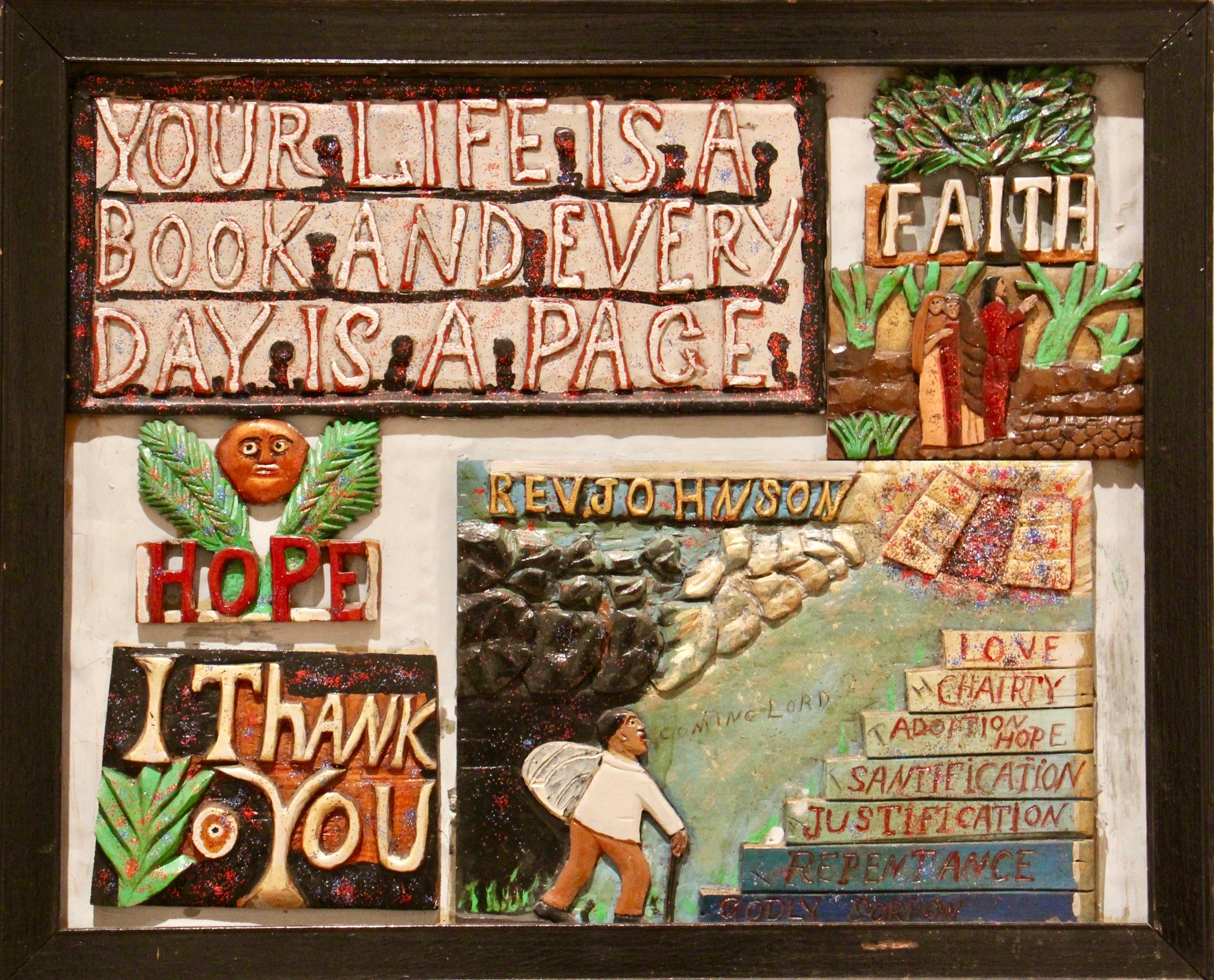

Elijah Pierce's America at The Barnes features more than 100 works by the 20th century African American woodcarver who worked as a barber and a preacher in Columbus, Ohio. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

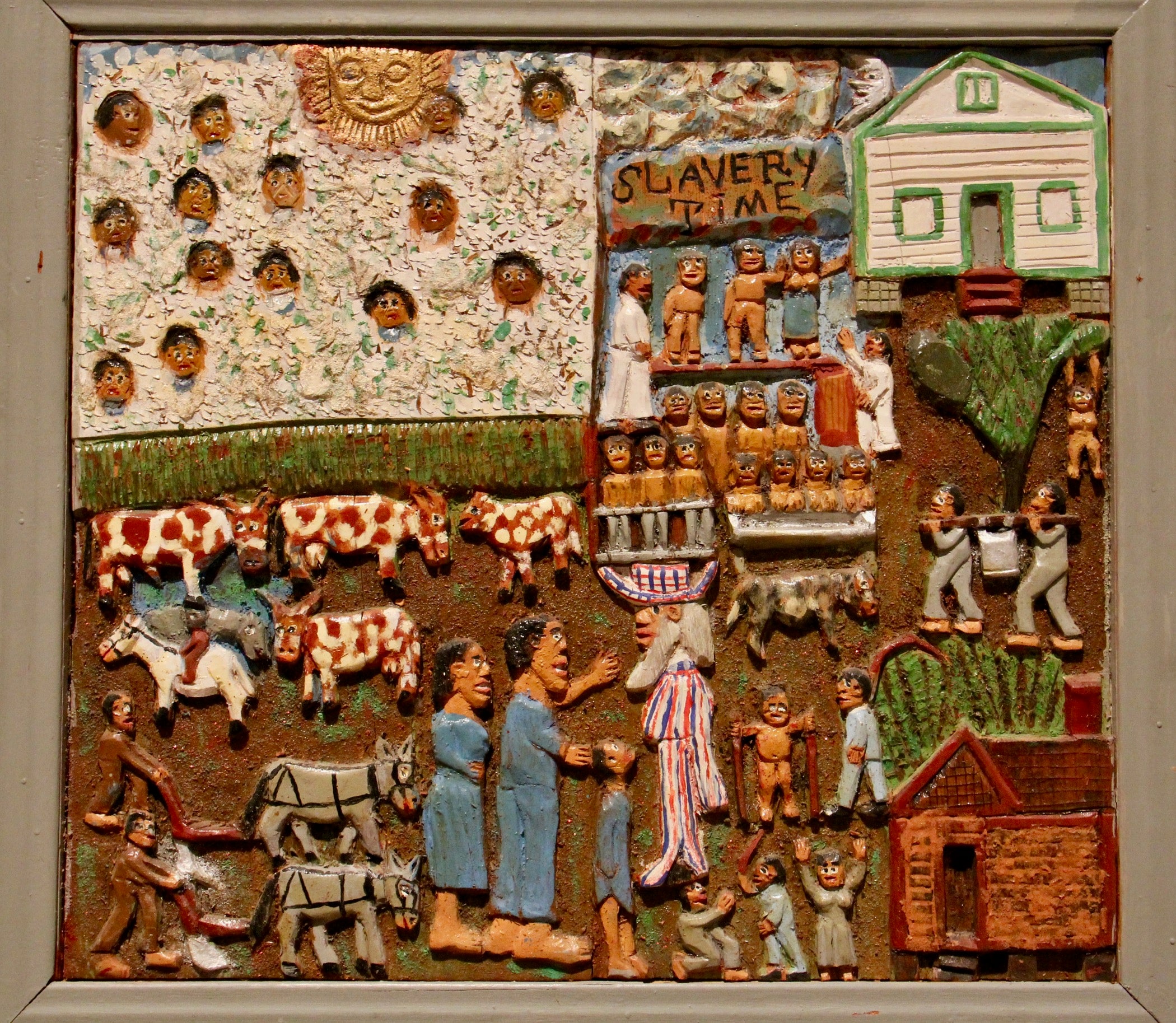

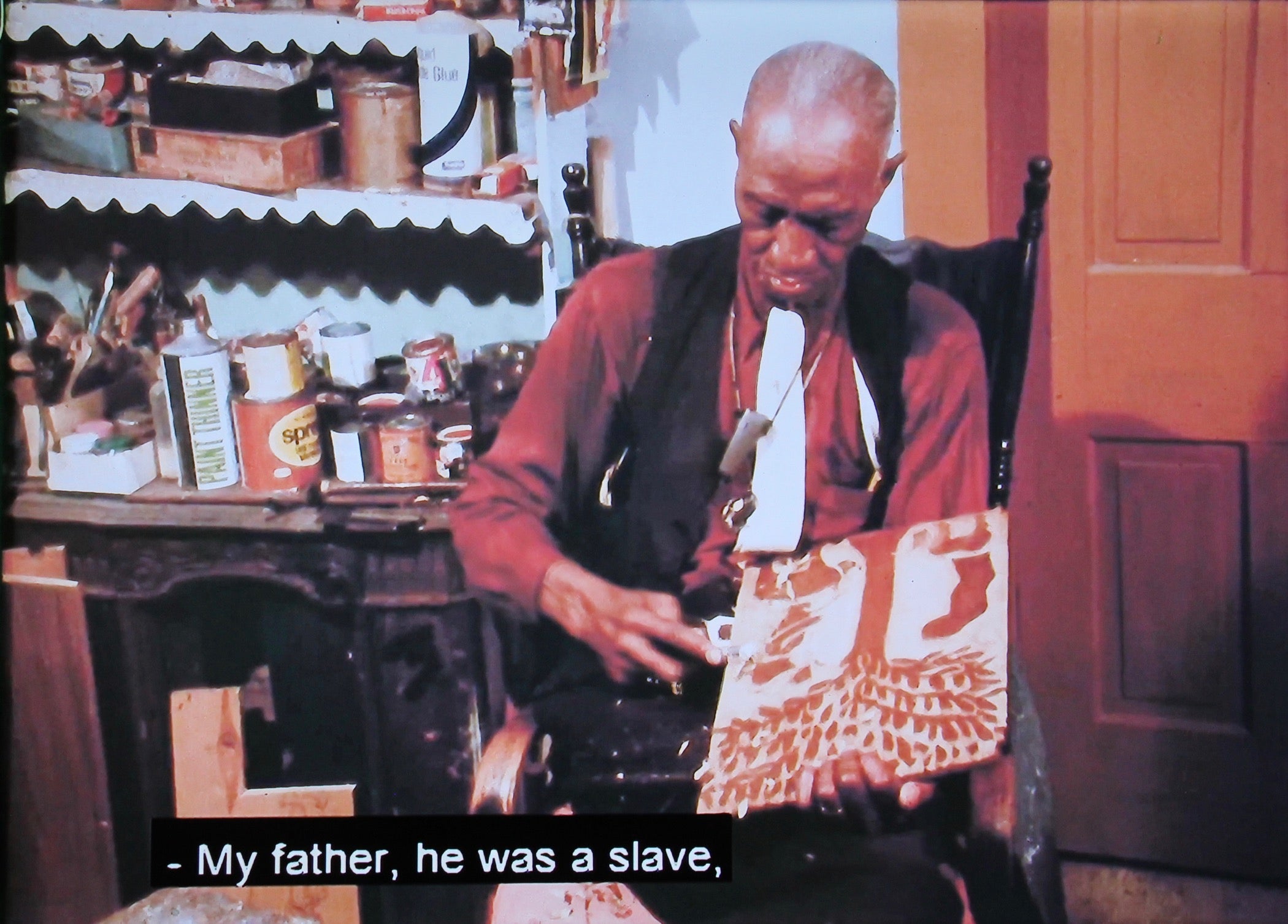

Elijah Pierce had the soul of a preacher, the hands of a craftsman, and the eye of a political cartoonist. About 107 of his pieces on display at the Barnes Foundation track more than a century of Black American life in sometimes graceful, sometimes roughly carved relief panels.

His carvings depict slave auctions (Pierce’s father had been enslaved in his early life) and cartoon characters (on display are two figures of Popeye: one white, one Black). He carved stories from both the Bible and politics of the day: scenes of the sins of Richard Nixon are carved at least twice.

“Every piece I carve is a message, a sermon,” Pierce is quoted in the exhibition catalog of Elijah Pierce’s America. He died in 1984 at age 92.

The show was put together by Nancy Ireson, the Barnes’ chief curator, with Zoé Whitley, director of the Chisenhale Gallery in London. This is not the first time an exhibition of Pierce’s work has landed in Philadelphia: he was the subject of a show in 1973 and again in 1994 for an exhibition that toured nationally.

However, neither Ireson nor Whitley had ever heard of him.

“I ask myself why,” said Ireson, who stumbled upon Pierce’s work in a museum a few years ago and was struck by the inventiveness of his carvings. “I was stopped in my tracks when I saw a piece by Pierce in the Columbus Museum of Art.”

She called Whitley, who in 2017 organized a celebrated exhibition at the Tate Modern in London, “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” which eventually came to the Brooklyn Museum. She had not heard of Pierce, either.

In the 1970s and 80s Pierce’s work was at the center of a growing interest in so-called “outsider” art, works by artists who were not formally trained and typically worked in a folk tradition or a highly idiosyncratic way. At the time, before he died, Pierce enjoyed a fair amount of recognition for his work.

Since then, after at least one generation of art professionals has passed, Pierce’s work may have slipped out of the mind of some in the art world. His work was fresh to the eyes of Ireson and Whitley.

“It was a moment to think about how we look at art history and ask questions about who gets included,” said Ireson.

Pierce earned a living as a barber and worked as a preacher. He carved whatever piece of wood found its way into his hands, sometimes a hunk of 2×4 lumber, or a plank of aged poplar.

“Sometimes I’d hear a song or go to church and hear a man preach a sermon, and a picture would form in my mind,” said Pierce, as quoted in the catalogue. “I’d get a piece of wood and start to carve it.”

In the show is a “Preaching Stick,” a hardwood billiard cue stick that Pierce kept in the barbershop. He occasionally whittled it with stories his customers would tell while they got their haircuts until the stick was full of carvings, an unhurried process that could take years.

During the Great Depression, when his barbering business was suffering, his wife got an idea that Pierce should carve several planks with Bible stories, which would be hinged together as a book. He traveled with “The Book of Wood” as a preaching tool, using the carvings as visual aids during sermons.

At the time Pierce did not think it was a good idea, but it worked. The novelty of the “Book of Wood” made the papers (there is a framed clipping in the exhibition) and the preaching tour was a success.

“He’s a storyteller,” said Ireson. “Because he was a preacher he had a real sense of how to hold an audience, how to get people to listen. There’s a performative aspect to the pieces. He had a talent for getting the right story and communicating it in a way that hits a nerve.”

Elijah Pierce’s America opens Sunday and is on view until January 10. It is the first new exhibition at the Barnes Foundation since it shut down in March due to the pandemic. The galleries reopened in July with face-mask requirements, limitations on the number of visitors, and marked walking paths through the exhibition spaces.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.