Bill Viola’s video art washes into Philadelphia

The pioneering video artist uses water and technology to explore consciousness and afterlife.

Listen 2:13

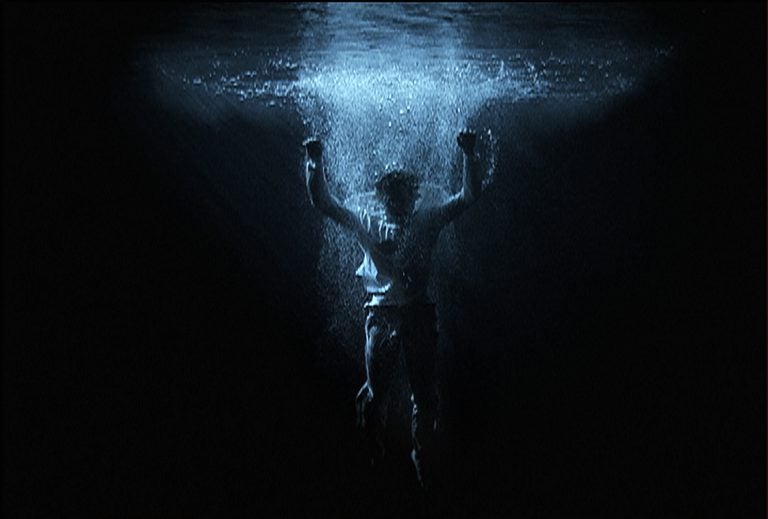

Ascension, 2000, is a video/sound installation by Bill Viola, part of an exhibit at the Barnes Foundation. (Photo: Kira Perov)

As a towering figure in the world of video art, Bill Viola’s work has been shown in major venues like the Whitney, Guggenheim, Getty, and Tate Modern museums, and represented the U.S. twice at the Venice Biennale. The Barnes Foundation new exhibition, “I Do Not Know What It Is That I Am Like,” is the first time a major exhibition of Viola’s work has come to Philadelphia.

When the Barnes set about putting together the 40-year retrospective, two other Philadelphia museums joined in the fray: both the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Fabric Workshop and Museum have re-installed their own room-sized works created by Viola, “An Ocean Without a Shore” and “The Veiling,” respectively.

One of Viola’s techniques is shooting extremely high-definition video of people doing seemingly simple things — standing in a line, meeting each other on a street corner, or moving through water — and then slowing down the footage to the point where the image seems to be still, but not quite.

“Once you slow down time you move into a different world,” said Viola’s wife and longtime collaborator, Kira Perov. “We’re not part of this world anymore. You move into a mystical world, perhaps, or you have time for reflection. We give the gift of time to people, to stay in a different world.”

Viola, 68, has suffered from ill health lately and could not attend the installation nor the opening of the exhibition.

One of the magic tricks of Viola’s work is that, on the surface, the concepts can be understood fairly quickly. You “get it” within a few seconds of looking. But sustained viewing of “An Ocean Without a Shore” with 24 people slowly walking through a sheet of falling water, can result in unexpected epiphanies.

“There’s a cumulative impact over time,” said curator John Hanhardt. “People become very emotionally attached. There are very powerful gestures as [the performers] touch the water and parade through it. They are telling a story about themselves as they come through.”

Viola’s works are abstract enough that they can be freely interpreted. Often they are seen as meditations on mortality, or spiritual reflections on the nature of corporeal bodies. Water often appears as a medium connecting the worlds of the living and the dead. His works are often described in terms of ghosts.

Hanhardt included in the Barnes’ exhibition “Pneuma,” a triptych of three projections of static onto three adjacent walls of a dark room. A close watching reveals vague imagery buried in the blur of white noise.

“It’s like when you close your eyes and you see shapes and forms from memory or from just before you closed your eyes,” he said. “These ghost-like images appear and disappear. They shape the surface of the wall. The edge of dream and reality.”

Unlike the Barnes Foundation’s main galleries with their storied assemblages of well-lit modernist paintings, the Bill Viola galleries are nearly pitch black, illuminated mostly by the glow of video monitors.

One gallery of Viola’s work shows how he has been influenced by painting, but not so much by the Impressionistic works by Renoir and Matisse on display in the Barnes’ permanent galleries. Rather, he channeled the 16th century Italian painter Jacopo da Pontormo to make “The Visitation,” and the legendary 17th century Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer for a 5-screen series “Catherine’s Room.”

The last installation in the exhibition is the earliest. “He Weeps for You,” (1976) is basically a leaky pipe and an amplified snare drum. A copper pipe suspended from the ceiling drips water into a drum head, which thunders through the room.

A closed-circuit camera is trained onto the drip and screened, in real time and greatly blown up, on the other side of the room. The image is so large that visitors to the installation can see their own figures reflected in the drip.

It’s the only piece in the exhibition where the visitors, themselves, are the subjects of the video.

“It’s a very, very difficult piece to install, because it’s all live,” said Perov. “There is no pre-recorded anything. A little drop of water has to drip down every 45 seconds. Just to get that to work is an extraordinary feat.”

The exhibition gets its title from a feature-length video in the Barnes’ auditorium, screening every Wednesday at 1 p.m. for the run of the exhibition and on additional selected days. Made over three years (completed in 1986) under the working title “Animal Consciousness,” the video is a compendium of sequences exploring time, nature, and self-examination.

The exhibition continues through September 15.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.