Barnes offers work of WWI Picasso, taking turns with theater and tradition [photos]

-

Young visitors gaze into a case full of game-worn NBA basketball jerseys. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Former Collingswood Mayor Jim Maley cuts the ribbon held by members of the DePace family. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

A massive vault at the back of the museum is used for storage, but may one day house the collection's most valuable items. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Tucked away in the corner of a shadowbox is a small trophy commemorating Wilt Chamberlain's 75-point performance when he played for Overbrook High School. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Dr. Nicholas DePace grins as his museum fills with fans and well-wishers on opening night. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

The museum displays about 15 percent of the DePace collection. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

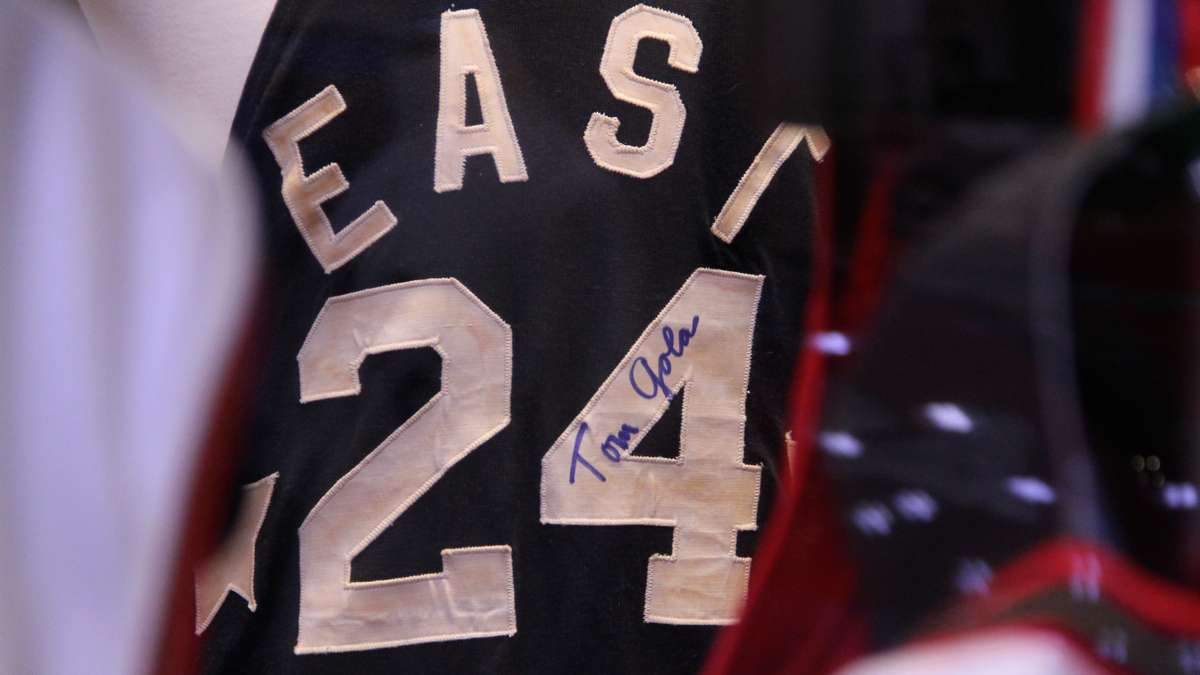

Tucked among an impressive collection of game-worn basketball jerseys is the autographed all-star jersey of LaSalle College's Tom Gola. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

A golf bag inscribed to Frank Sinatra is revealed to be an elaborate ruse to end a feud between the singer and Joe DiMaggio. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

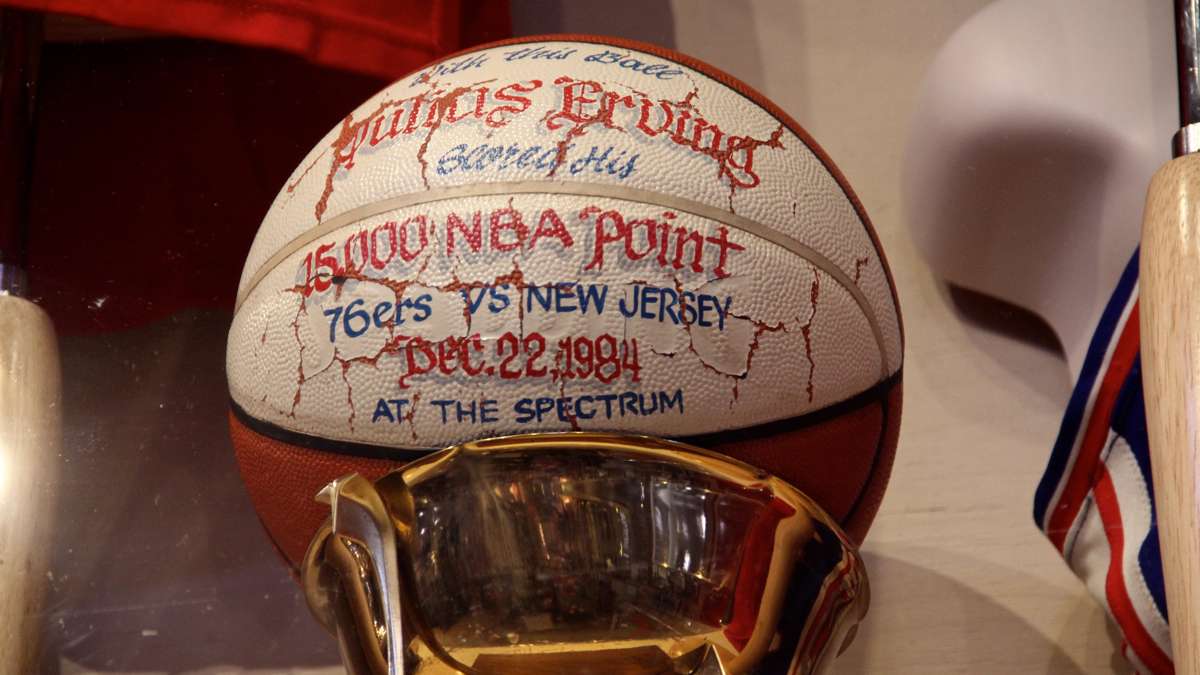

The ball Julius Erving used to score his 15,000th NBA point. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

A helmet and football used by Jim Thorpe occupies a glass case in the center of the museum. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

The items on display at the DePace museum, about 15 percent of the total collection, focus on Philly sports. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

The museum includes a room dedicated to the Philadelphia Athletics baseball team. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

A basketball jersey display includes one signed by Darryl Dawkins, also known as Chocolate Thunder. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

The DePace Sports Museum occupies a former bank on Haddon Avenue in Collingswood. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

A section of the museum dedicated to olympic sports features mementos from the 1980 'Miracle on Ice' U.S.A hockey team, including the goalie mask worn by Jim Craig. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

The collection includes robes worn by Philadelphia boxing great Joe Frasier. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

This weekend, the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia debuts an exhibition of work by Pablo Picasso painted during World War I, a time the artist appeared to keep the war at arm’s length.

By 1916, most of the able-bodied young men in Paris were recruited to fight against Germany, including most of the artists in Picasso’s crowd. The artist with whom Picasso developed cubism, Georges Braque, enlisted and suffered a head injury in combat and was temporarily rendered blind.

As a Spaniard in Paris, Picasso could not enlist. But men who avoided the war were considered fainéant (shirkers). Cubism, itself, had become problematic during the war. Although developed in France largely by a Spaniard, it had become critically aligned with Germany — the enemy.

Picasso found himself in a tight spot.

“Cubism was seen as nonpatriotic, and he was the high priest of cubism,” said Simonetta Fraquelli, curator of “Picasso, the Great War, Experimentation, and Change,” now at the Barnes Foundation.

With war raging outside the city, Picasso spent a sunny August day having a good time with poet Jean Cocteau, artist Max Jacob, and other friends in the sidewalk cafes in bohemian Montparnasse. On a whim, Cocteau borrowed his mother’s Kodak. The resulting photographs are included in the show.

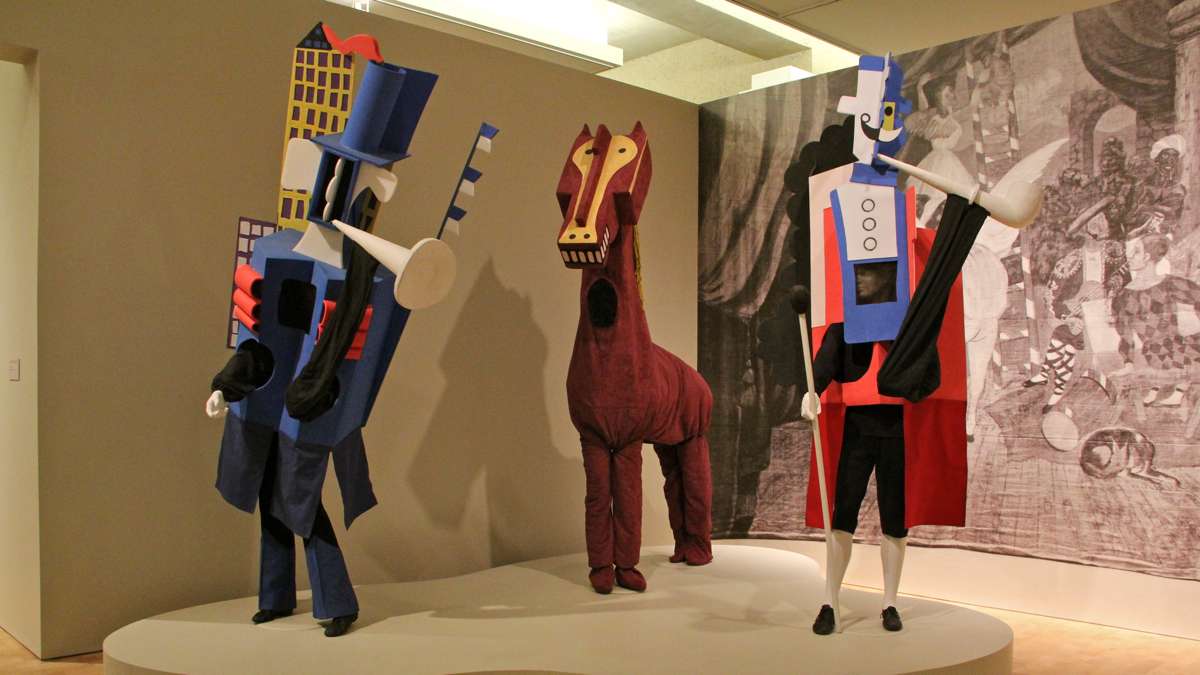

Between snapshots, Cocteau asked Picasso if he would design the set and costumes for a new ballet he was working on with composer Erik Satie for the Ballet Russes. Called “Parade,” it is a one-act scenario about circus performers trying to woo an audience into their tent.

To everyone’s surprise, Picasso accepted the theater gig.

Those costumes are cubist paintings come to life, some of them farcically so: cut-up buildings arranged with arms and legs, resembling a walking mascot of a skyline from a fevered dream.

His involvement with the ballet led to his involvement with one of its dancers, Olga Khokhlova, who would become Picasso’s first wife.

At the same time, Picasso was drawing and painting conservative portraits in a much more traditional, figurative style. This also shocked the art world, which saw Picasso as the driver of the avant-garde.

“His paintings of Olga in this period are all figurative,” said Fraquelli. “She came from a bourgeois family; she was much more traditional. Was he choosing to paint her that way because that’s how she wanted to be seen? Was that the way he identified her?”

The exhibition features many works done in a classic, sometimes academic style. Why Picasso chose to work in this mode is anyone’s guess. One theory posits his more conservative approach may be an expression of Picasso’s French patriotism: a nod to the old French masters and their neoclassical style.

Fraquelli suggests Picasso moved deftly between Cubism and neoclassicism. She hung an abstract work right next to a straightforward figurative work, both painted in 1918, both of clowns, “Harlequin with Violin” and “Pierrot.” Each borrows techniques from the other.

“They are related to each other,” said Fraquelli. “And the subject matter. They are both commedia dell’arte figures. Picasso himself identified with the harlequin.”

Picasso did not paint the war directly. It was 20 years before his antiwar “Guernica” painting, about the Spanish Civil War. However, World War I likely influenced his decisions on style and subject matter.

The exhibit continues through May 9.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.