As Zipcar passes the 400-car landmark, what’s next for car-sharing in Philly?

Over at Citified, Malcolm Burnley has been building the case for turning more of Philadelphia’s on-street and off-street parking spaces into dedicated spaces for short-rental vehicles like Zipcar and Enterprise.

Burnley’s case that we should make it easier for rental companies to rent dedicated publicly-owned spaces on the street may rub some people the wrong way (isn’t that privatization of public space?), but he makes two main points to argue that this would actually be in the public interest.

The first point is that short-rentals take cars off the street, slackening the demand for curb parking.

A few different studies and models have found that a single shared vehicle can replace between 9 and 13 privately-owned vehicles in urban areas. PhillyCarShare, the non-profit that pioneered the car-share model in Philadelphia in 2002, before its acquisition by Enterprise in 2011, estimated in 2007 that the service kept 15,000 vehicles off the streets.

The reason this works is that in any urban neighborhood, there are a lot of cars that are used only infrequently.

Where I live in Bella Vista, only 41% of households commute to work by car. But about 62% of households own cars– a 21 percentage point difference! What’s happening with the rest of those cars? They’re mostly sitting on the street waiting to go to the grocery store or the mall sometimes. Many don’t get moved for weeks on end. If there were more shared vehicles around, some of the folks in that group would get rid of their cars.

Burnley’s second point is that the tight markets for essentially free curb parking in the neighborhoods drives the political support for regressive policies like minimum parking requirements that force non-drivers to subsidize their neighbors’ parking in their rent, and that makes housing more expensive. So the issue is actually a lot bigger than mere parking.

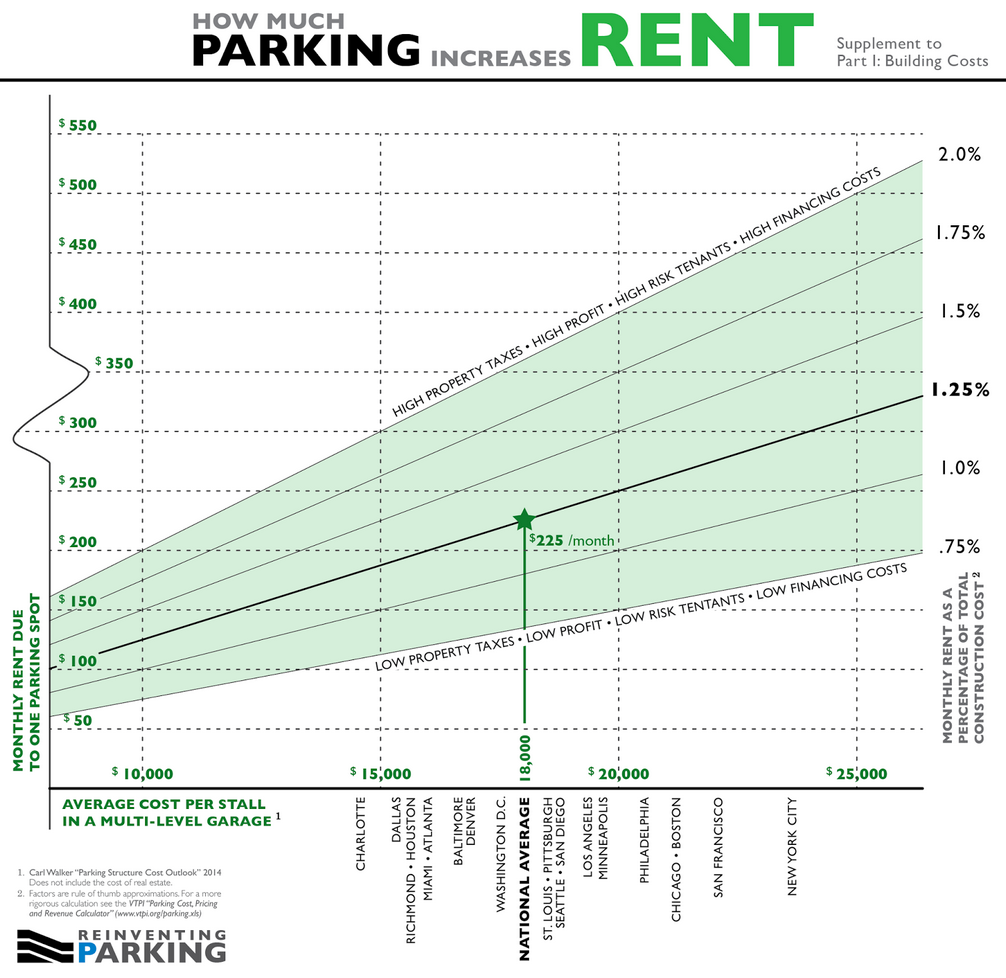

As Burnley points out, minimum parking requirements can increase rents by as much as 50%. Just today, the site Reinventing Parking released this graphic in a blog post analyzing the impact of bundled parking on rents in different US cities. Read the post for more on their methodology, but they find that Philly comes in above the national average, with bundled parking bumping up rents by about $250 a month on average.

Piece it all together, and you can see the contours of a story where having more shared vehicles around the neighborhood leads to lower rates of car ownership, and lower car ownership and less parking stress opens up more political space to talk about allowing developers to provide more car-free housing options. That, in turn, increases the appeal of having more shared mobility options around, and on and on in a virtuous cycle of car attrition and cheaper housing.*

According to Jessica Smith, Fleet Operations Manager for Zipcar Philly, the market for short rentals has only been growing. Just last month, Zipcar passed the 400 vehicle mark in Philly–the most they’ve ever had–and their fleet now stands at 432 Zipcars. The size of the fleet varies by season. In the spring, they “in-fleet” between 100 and 125 brand new vehicles for peak season, and then they remove older vehicles from the fleet late in the year. But even after they thin the fleet this year, they’ll still have around 400.

Zipcar representatives say they’ve expanded throughout the city and region, but not surprisingly, their strongest markets are Center City, University City, and South Philly. Smith says expansion in South Philly has been slower because of the difficulty securing parking spaces.

What’s been difficult about it? It’s not the money. PPA rents out publicly-owned spaces to rental companies on the cheap. For each dedicated space, whether in a parking lot or on-street, the PPA charges rental companies just $150 a year.

Smith says that’s cheaper than what they pay for parking on privately-owned land, but private lots still account for most of their recent expansion in the greater Center City area. The price of private parking fluctuates with the cost of land, and Zipcar reps didn’t offer an average, but for some context, $150 buys you a bit less than a week in a typical privately-owned Center City parking lot.

Malcolm Burnley raised an interesting question as to why developers aren’t taking advantage of the city’s incentives to provide car-share spaces in new development, since each shared vehicle space counts toward four regular parking spaces mandated by the zoning code.

I’m more interested in why, given what seems like a clear arbitrage opportunity in the spread between more expensive private spaces and price-controlled PPA spaces, we aren’t seeing Zipcar and Enterprise more aggressively going after the ultra-cheap PPA spaces.

The reason appears to be that the process the city has devised for renting out PPA-managed spaces adds too many soft costs to be worth it for rental companies to spend the time pursuing them.

If Zipcar or Enterprise wants to rent just one publicly-owned parking space, they need a letter from the adjacent property owner (if applicable), they have to make a presentation to the local Registered Community Organization (RCO) and get a letter of support from them, and they also need a letter of support from the District Councilperson.

That’s a lot of staff time commitment for relatively little pay-off, which explains why Zipcar added only two new on-street spaces in the last year, at Cumberland and Gaul, and 25th and Locust.

Zipcar has a total of just 11 off-street spaces, while Enterprise has 74. As mentioned above, Enterprise acquired PhillyCarShare in 2011, which had a head start amassing spaces since 2002.

Tanya Seaman, one of the co-founders of PhillyCarShare, says it was just as hard to get curb spaces as a non-profit, and PCS had to employ some scrappy tactics to win on-street spaces in South Philly.

“Some of [the on-street spaces we secured] were spaces where there had been construction and they had just never bothered to put back the sign allowing parking,” she said, “My partner and I walked every single street and identified 120 spaces where there was enough space behind a Stop sign or something like that to put a car. And we had smaller cars so the Parking Authority let us get away with having smaller spaces.”

The on-street spaces were valuable, she said, because they doubled as marketing. The higher visibility on the street contributed to the sense that you could still get access to a car at a moment’s notice if you needed one. But to get the network to the point where it could offer high levels of access and proximity, they needed to prove to neighbors that it was worth surrendering some parking spaces.

“When we did this first in Queen Village, people were very concerned about losing a parking spot,” she said, “so we agreed to do a report on how many members we had gained because of that spot, so they would understand how many parking spaces we had freed up by placing one of our cars there. And it was actually extremely effective. The data proved we could be very successful with having on-street spaces, and they could get what they wanted too”.

Getting Council and community group approval was still a time-consuming process, but the required outreach wasn’t a waste of time then because it helped get the word out about a service that was unfamiliar at the time, and helped educate neighborhood activists about the role of shared vehicles in relaxing parking demand.

Now that most urban-dwellers seem to know what car-sharing is, though, Seaman thinks the city’s extensive outreach requirements to rent just a few parking spaces are excessive. She points out that the community meetings aren’t an important check on Zipcar taking too many public parking spaces, because they’ll lose money if they saturate the market too much.

“It doesn’t make a lot of sense to have to do all that for a couple of reasons,” she said, “At this point, Zipcar’s not going to take over more spaces than they need, because they’ll just end up having more cars than they need, and that means less profit. It would be hard for them to abuse the system at this point, I would think.”

In 2014, Zipcar secured a deal with Washington, D.C. where their fleet of 850 Zipcars can park for “free” in any metered space or residential permit zone, and the company cuts the city a check for $255,000 a year–about $300 a vehicle, and twice what rental companies pay for PPA spaces annually. Car2Go, a point-to-point short-rental service not yet in Philly, pays D.C. over $500,000. Check out that article for more on D.C.’s approach to auctioning public parking spaces.

Looking ahead, Zipcar is seeking 150 “park anywhere” permits in a similar arrangement with Boston, and if that pans out, observers expect they’ll pursue similar deals with other cities allowing their vehicles to park anywhere for an annual lump sum payment.. Zipcar Philly reps said they would eventually like to see a similar deal here, so don’t be surprised if this issue winds up on the legislative agenda in the next administration.

*Whether a looser market for curb parking is even achievable when residential parking permits aren’t just underpriced but subsidized by the city is an interesting policy question. In the absence of any financial penalties for keeping a car in the neighborhood, short-rentals might be used more by Philadelphians as a replacement for a second or third car. Indeed, about 32% of Philadelphia Enterprise members still own at least one other car–the highest percentage of the five cities the company surveyed.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.