As it fills in final missing bits, Philly’s nearly-complete city plan exposes gap between neighborhood hopes and political realities

As Samantha Petty considered the Planning Commission’s proposals for her community, she experienced a wave of déjà vu.

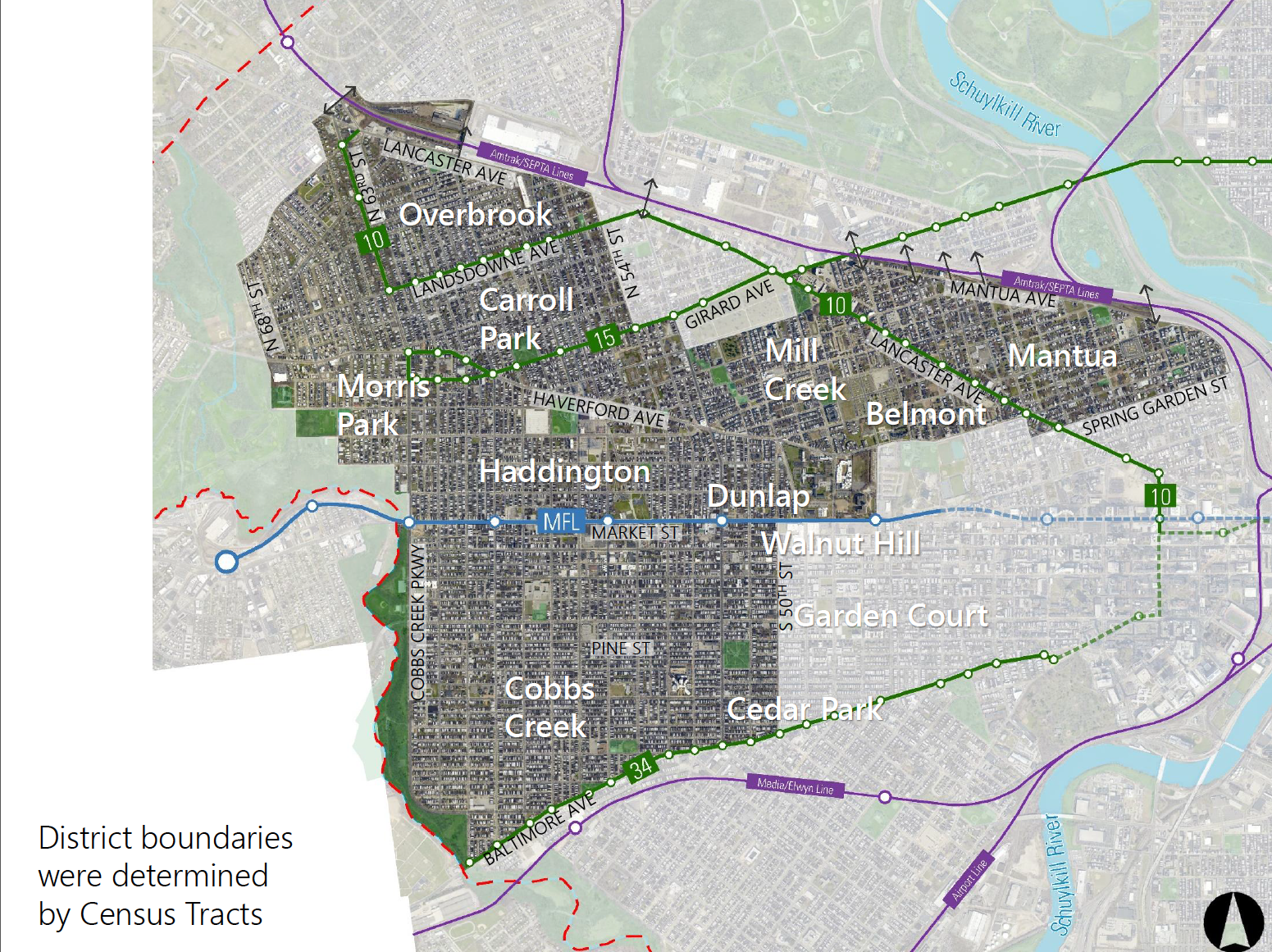

Standing in the hallway of West Philadelphia High School, at the last public outreach meeting about proposed policies for the “West District” — one of 18 city subsections to undergo the comprehensive planning process begun six years ago — the West Philadelphia mother flashed back to her work as an urban planner in Portland, Oregon circa 2011.

There, she helped craft a bicycle infrastructure program meant to bring greater safety to one of the city’s busiest thoroughfares. But the miniscule construction project provoked backlash from the local African-American community, which saw it as a manifestation of gentrification.

West District’s Mantua Greenway, which will connect the low-income neighborhood to the Schuylkill River Trail by bike and foot, reminded her discomfitingly of hard lessons learned on the West Coast.

Petty rushed off to find Brian Wenrich, the city planner for West Philadelphia.

Mapping The City’s Future?

The West District is one of the final parts of the city’s comprehensive plan, known as Philadelphia 2035, a legacy of Mayor Michael Nutter’s effort to give direction to Philadelphia’s development and growth. For decades, the Planning Commission, which is staffed by dozens of zoning and land-use experts, had operated in an ad hoc fashion dictated by the political moment. The zoning code of 2012 and the new comprehensive plan, both of which hadn’t been updated since the mid-20th century, are meant to give policymakers a clear and rules-based guide for the city’s future.

The engagement process around the district plans, consisting of online feedback and three public meetings, is meant to give neighborhood residents a voice in how the city allocates attention and resources. The planning process also offers an opportunity to give input on how neighborhood zoning maps, which largely dictate what can and can’t be built on a given city block, could be rewritten. It is meant to be an empowering process.

But the district planning process can also be confusing for participants and grueling for planners. For many attendees, the Planning Commission’s civic engagement sessions are the only time where city representatives gather residents and solicit feedback on anything. The planners are then bombarded with questions about issues that they have no control over, like the diversity requirements of the Rebuild initiative.

Most attendees are civil and excited to participate in a vision of their future community, but some treat city workers with suspicion and hostility. At the final meeting, one man stormed out of the introductory presentation, yelling that the rest of the attendees were being played for dupes. Later, an irate woman had to be escorted out by security.

But even when the district planning process runs smoothly, there is still a tension between the stated goals and the reality of how change occurs in Philadelphia.

The Planning Commission ultimately falls under the purview of the mayoral administration, which can unilaterally act on some of the commission’s capital spending recommendations, such as adding light fixtures to a neighborhood street. But it’s the district City Council members that control zoning and, to a large extent, other major policy decisions like land sales and the placement of bike lanes.

That often isn’t clear to the average resident.

“Welcome to Philadelphia, where councilmanic prerogative rules,” said John Landis, professor of city planning with the University of Pennsylvania. The Planning Commission’s district plans can provide a roadmap, but it’s up to the council members representing those areas to drive the changes, as they have final say over land use and zoning in their districts.

“[District plans] provide an additional channel through which groups can make their aspirations known,” said Landis. “How that information is acted upon isn’t clear, and that can be frustrating. People often participate with the assumption that the distribution of funds, or other things they want, is going to change. No one is promising that.”

For example, Petty, the former Portland city planner, proposed moving vacant land around the forthcoming Mantua Greenway into the city’s land bank, which would theoretically give the public a say over how city-owned land is used by the subsequent purchasers.

But that would require action from Councilmember Jannie Blackwell, not the Planning Commission or even Mayor Jim Kenney. Whether the West District plan gets put into action or collects dust on a shelf depends largely on Councilmember Blackwell.

“You’ve got to put as many properties as possible into the land bank before the Mantua Greenway opens,” Petty told Wenrich, West District’s lead planner. “We really got burned because we didn’t do that around our bikeway [in Portland].”

Petty worries about gentrification: The bikeway in Portland attracted a lot of bicycle-centric new development, higher income residents, and rising housing prices. She felt Portland could have saved longtime residents pain, if the city put vacant parcels along the bikeway into a land bank and developed affordable housing.

“It’s really important to learn that even small infrastructure investments could generate a lot of real estate investment in the context of a pretty booming economy,” said Petty. “Immediately tying affordably to infrastructure investment, that was the lesson we learned in Portland.”

Wenrich thanked Petty for her advice and assured her that he’d recommended just such a course to Councilwoman Blackwell. But, he cautioned, the Planning Commission and its staffers play a purely advisory role.

Although Weinrich did not say so, it is unlikely Blackwell will take him up on that particular idea. In her 24 years in City Council, she has been slow to adopt newer land use initiatives, especially those proposed under the Nutter administration. Blackwell hasn’t placed any parcels in the land bank since it opened in late 2015. Until recently, she only rarely updated her district’s zoning maps, many of which date back to the 1950s. In 2013, Blackwell held hearings on the district planning process because she did not like the fact that the Planning Commission was making land use recommendations.

Blackwell’s office did not return several requests for comment on Tuesday about the West District plan.

That isn’t to say Blackwell is reflexively opposed to the Planning Commission or unique in protecting her prerogatives: Much of any district City Council person’s power stems from their power over land use and zoning. And Blackwell surprised her critics earlier this year, when she became the first councilperson to take advantage of new zoning options to encourage transit-oriented development.

“Some councilmembers are very invested in the idea that all land use decisions go through their office first and are suspicious of non-elected civil servants,” said Alan Greenberger, who lead the Planning Commission during much of the comprehensive planning process as deputy mayor under Nutter.

“It’s an uncomfortable change for some, but not for others,” said Greenberger. “I was hopeful that when councilmembers saw the value they would eventually embrace it. A logical argument doesn’t make someone change their mind on a dime about something they’ve believed for decades.”

“The argument from Council is that they know how to get things done so they are in a better position to produce outcomes,” said Landis. “The argument against that is just by the nature of politics City Council will be more interested in individuals they know and trust and have worked with before. Whereas a community planning process will include persons who aren’t in the City Council person’s loop.”

The West District plan includes a proposal to preserve the area’s preponderance of single family homes by changing the neighborhood’s zoning, which currently would allow developers to build large apartment or condo buildings. The plan also calls for guiding such denser development towards commercial corridors and transit stations by upzoning parcels around these locations.

Such remapping is a major part of the district plan, but that’s no guarantee that it will be enacted.

A recent Planning Commission study found that less than half of the acres where remapping has been proposed have seen it enacted. Most of the action stems from just three City Council members: Bobby Henon, Maria Quiñones-Sanchez, and Council President Darrell Clarke. Throughout the meetings about the West District, an undercurrent of tension periodically flowed through this corner of the city, where private divestment and a lack of public resources have soured residents on the city’s ability to deliver. Still, the planning process itself, coupled with some of the popular proposals emerging from it, raised expectations for positive changes among many who attended the sessions.

“I’m actually really impressed that the city would have this much concern for the residents and their input,” said Aaron Winthers, a Willow Grove resident who is considering moving to West Philadelphia and attended the district planning meeting to get a feel for the neighborhood.

Injecting optimism among an understandably jaded populace comes with the risk of entrenching a deep cynicism if those raised hopes end up dashed. While some residents might chalk up inactivity to the disconnect between councilmanic control of land use and a purely advisory planning agency, many will just see the inaction — no matter the structural causes — as another promise unkept.

“It’s a tricky position,” said Greenberger. “The plan is meaningful in the sense that it coordinates the values of people in a set of unified aspirations for how things ought to go. But there’s that disconnect between stated goals and actually getting things done.”

Hi there, read PlanPhilly often? The news that you read today is only possible because of your support. Please help protect PlanPhilly’s independent, unbiased existence by making a tax-deductible donation during our once-a-year membership drive. We cannot emphasize enough: we depend on you. Thank you for making us your go-to source for news on the built environment eleven years and counting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.