As feds set carbon rules, a renewed interest in nuclear power

Listen

Three Mile Island's Unit 1 reactor is still operational and provides enough power for 800,000 homes. Unit 2 partially melted down in 1979. (Joanne Cassaro/WITF)

The Three Mile Island power plant has a conspicuous place near the Pennsylvania Turnpike and in the history of the world’s nuclear power industry.

The Three Mile Island power plant has a conspicuous place near the Pennsylvania Turnpike and in the history of the world’s nuclear power industry.

Drive east over the Susquehanna River in Dauphin County and you’ll see steam emanating from only two of TMI’s four cooling towers. That’s because one of its reactors partially melted down in 1979. It was the worst nuclear accident in United States history.

[Part three of five]

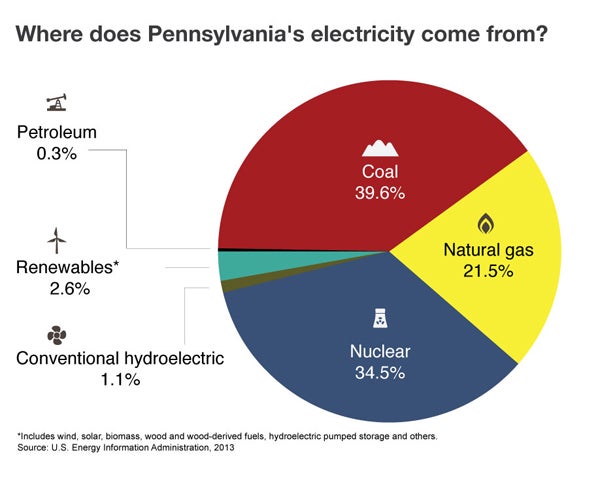

Pennsylvania is third in the nation for energy production. It’s also in third place for carbon dioxide emissions. As the federal government pushes states to cut emissions that are leading to climate change, StateImpact Pennsylvania profiled five major energy sources: coal, wind, nuclear, solar and oil.

Exelon Corporation Three Mile Island

The Three Mile Island power plant has a conspicuous place near the Pennsylvania Turnpike and in the history of the world’s nuclear power industry.

Drive east over the Susquehanna River in Dauphin County and you’ll see steam emanating from only two of TMI’s four cooling towers. That’s because one of its reactors partially melted down in 1979. It was the worst nuclear accident in United States history.

Unit 1 is still operational. It’s run by Exelon Corporation.

Before we can go inside, company spokesman Ralph DeSantis takes us to a security checkpoint where we meet heavily armed guards. They check our names, social security numbers, and birthdates. We pass through a metal turnstile and reach more security. It looks a bit like an airport, with a metal detector, x-ray machine, and an explosive detector.

Once we make it through, DeSantis takes us to TMI’s Unit 1 reactor.

“This is the reactor building,” he says, pointing to a wall of concrete that’s four feet thick. “Right on the other side of this wall is where the reactor is. That’s where the chain reaction is occurring.”

At full capacity, the plant generates enough electricity for 800,000 homes.

It’s one of five nuclear power plants in Pennsylvania — together they account for about 35 percent of the state’s electric generation. Only Illinois has more nuclear capacity.

Supporting nuclear energy?

Under new rules proposed by the federal Environmental Protection Agency, Pennsylvania will have to cut its carbon emissions by 32 percent over the next 15 years.

As EPA Region Three Air Director Diana Escher explains, the state can choose its own way to meet that target.

“I would not describe us as supporting nuclear energy in this plan at all,” she says. “It’s very flexible for the states.”

But in its proposed rules, the EPA cautions states against prematurely retiring their nuclear fleets. The agency also suggests expanding nuclear power as a way to meet emissions targets.

All but one of Pennsylvania’s nuclear plants recently received a license renewal to operate for another 20 years. Only the Limerick plant in Montgomery County is still going through the process.

Environmental advocates remain deeply divided about nuclear power. On the one hand, it’s praised as the ultimate, reliable low carbon power source. On the other hand, when things go wrong, it can be disastrous.

In the United States, safety is overseen by the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Spokesman Neil Sheehan says plants now need to have more redundant safety equipment to prepare for catastrophic events that happen off-site – like the earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan’s Fukushima plant in 2011.

“We are still in the early stages of seeing these implemented,” he says. “But we think, already, with some of the changes made, that these plants are even better protected than they were before.”

Susan Stranahan won a Pulitzer Prize as a member of the Philadelphia Inquirer staff for her coverage of the Three Mile Island accident and recently co-authored a book on the Fukushima disaster.

“I think that the nuclear industry has not learned its lessons,” she says.

She believes nuclear power can help curb climate change, but she doesn’t want to see it expanded.

Stranahan says the current 10-mile evacuation zones around plants are inadequate and external threats, like floods, still pose significant risks.

“I think the fact that we have not had a nuclear accident in this country since 1979 has lulled people into a sense of complacency.”

The waste issue

One of the lessons from the accident was the need for more training. Ralph DeSantis shows us inside TMI’s control room simulator. It’s an exact replica of the real thing.

“Essentially, the technology, much of it is the original equipment that we maintain,” DeStantis says.

On the surface, it doesn’t seem to have changed much since the plant came online in the 1970s. The control panels have big buttons and dials, with a few digital displays. The color scheme is 70’s sea-foam green.

Despite the décor, the plant still attracts young workers, like 23-year-old Heidi Nafis. A self-described environmentalist who grew up outside Chicago, she says she feels good about working to make energy so efficiently. Although it’s always a conversation-starter when she tells people she works at Three Mile Island.

“There’s a set of standard responses varying from Simpsons jokes to ‘Oh you glow at night,’ to ‘Is it still running?'”

But longtime Harrisburg activist Eric Epstein says he seen many promises made and broken over the years when it comes to cleaning up the site. He chairs the local watchdog group, Three Mile Island Alert.

One of his main concerns is the United States still has no policy on where to take its nuclear waste. So plants around the country are storing it on site.

“There is no economic incentive to clean TMI 2 up, there’s nowhere to take the waste, and that creates a crisis,” Epstein says. “I believe that crisis will be kicked down the road to future generations, which in my mind is unfair.”

In 2009 Three Mile Island was re-licensed to operate until 2034. At that point, both reactors will be dismantled together, over a 10-year period. Plans call for a full restoration of the site by 2054, 75 years after the accident.

Credit: Rachel Feierman for NewsWorks/WHYY

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.