As Baltimore Avenue changes, new signs honor ‘current history’

Najaye Davis cleans signs after they are cut by a laser cutter. (Jonathan Wilson for WHYY)

This article originally appeared on PlanPhilly.

—

Brian Cirksey spent some time walking along Baltimore Avenue earlier this year, talking to people he encountered, and doing some soul searching about what made the popular Cedar Park thoroughfare a place people loved.

Many of the stories he heard were about watching cool, small restaurants and shops, often started by immigrants, pop up on the avenue and shape its character as they flourished and grew. While he already knew the area, over the course of his conversations he found out much that was new to him. A restaurant he often walked past used to host dance parties in its basement, he learned. Modest Davis Pharmacy was 114 years old and still managed to compete successfully with Amazon.

“People know the owners, the staff, and it’s very friendly,” said Cirksey, a 51-year-old business consultant who lives a few blocks from the avenue. “Hearing the people talk about the businesses caused me to think, ‘wow, these businesses all have really interesting stories.’”

Stories, he thought, that should be seen. Enter West Philadelphia’s newest street signs — a collaboration between Cirksey, 17-year-old craftsman Najaye Davis and Tiny WPA, a community design nonprofit.

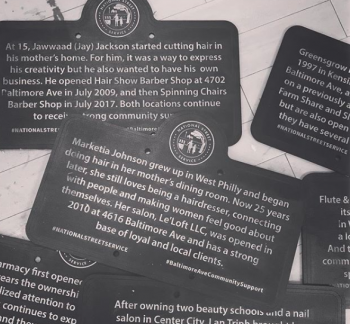

The wood signs, painted black with gold lettering, resemble official Pennsylvania historical markers. But instead of history cribbed from textbooks, the signs describe the origins of local establishments. “Current historical markers” is what Cirksey calls them.

“From a home-based operation cooking food in the backyard under the ‘blue tent’ to its current location at 4728 Baltimore Ave., Vientiane Café has grown because of the support of local residents,” reads the sign Cirksey posted outside the popular Lao and Thai fusion restaurant.

Sunny Phanthavong is the general manager at Vientiane Café. She knows that history intimately; her parents opened the restaurant in 2002. Cirksey’s sign has helped deepen the relationship between her family’s business and their West Philly community, she said.

“What he did was to highlight those stories for businesses in Philadelphia, why we’re here and why we do what we do,” Phanthavong said. “People are like, ‘I didn’t even know that. I didn’t know the backstory behind your family business.’ It’s nice to get that confirmation as I’m back there, working, cooking, on my feet 10 hours a day.”

Last week, Cirksey made and posted another eight signs for businesses such as Greensgrow West, African Audio Video, Dahlak Restaurant, and Spinning Chairs Barber Shop.

Many of them have been on the avenue long enough to witness its transformation from a struggling commercial corridor pocked with vacancies to a thriving shopping destination in an increasingly desirable neighborhood where apartment rents jumped an average of 60 percent between 2010 and 2014, according to a 2014 report by real estate analyst Kevin Gillen.

The change accompanied a striking demographic shift in the formerly majority-black district. Cedar Park’s black population fell from 65 percent of residents to 28 percent between 2000 and 2014, while the white population rose from 25 percent to 53 percent, according to research by Pew Charitable Trusts. Neighboring Walnut Hill and Spruce Hill experienced similar rapid changes.

In Spruce Hill, residents of some of the few remaining affordable apartment buildings are battling landlords over eviction orders as owners seek to cash out and upgrade newly desirable properties.

On Baltimore Avenue, merchants say they have benefited from the neighborhood’s increased wealth and popularity — and that customers are happy to see them flourish, and preserve the street’s diverse, homegrown feel.

“People that have been in the neighborhood are happy to see, like, ‘oh, yeah, we still have regular guys like you just owning and operating businesses on Baltimore Avenue with all the change going on’,” said Jawwad (Jay) Jackson, whose Hair Show and Spinning Chairs barber shops are featured on one of Cirksey’s new signs.

“A lot of people that come to Spinning Chairs, they want to know how I got started, how long I’ve been doing it. I get those questions a lot. The signs mean a lot, because people want to know the history. And then they also want to know, have these businesses been around before the changes,” he said.

The new batch of markers were finished up last week at Tiny WPA’s Lancaster Avenue workshop. Cirksey was there Tuesday night, tweaking the wording of a sign, while Davis watched over a laser cutter that was noisily searing captions into the sign’s faces and cutting them out from their wooden frames.

Davis, a TECH Freire Charter School student, is part of Tiny WPA’s Building Hero maker-training program and a regular presence in the nonprofit’s busy workshop. He stood in front of a computer, clicking through software that controls where and how deep the machine cuts. As he pointed out elements of the design, a laser under a glass cover scanned across a half-finished sign. Each time the laser hit the wood, a small burst of flame flared up.

“You see there’s different colors?” he said, pointing to lines on the computer screen. “The red’s actually cutting the sign out, and the blue is a score line, which makes the design. The black is the engraving, to emboss the logo.”

The street signs are latest of many objects Davis has fashioned over the last several months, using several types of design and cutting machines he’s learned to operate. Stepping away from the laser cutter, he showed off some of the others, including keystone-shaped apartment number markers for a building on Callowhill Street, signs for age-friendly benches in Mantua, and small markers for historic homes in Fairmount Park, made from the park’s downed trees.

Tiny WPA is an arm of a local design firm called Public Workshop. The organization has made a name for itself through projects that train children and teens to make playground equipment and street furniture with their own hands. The Building Hero project gives participants a chance to learn workshop skills and earn money for their work.

“We’re starting to do more and more partnerships around products that give you this sort of multiple bottom line,” said Alex Gilliam, the designer who heads Public Workshop and co-founded Tiny WPA. Gilliam pointed to Davis and the signs he has crafted. “In this case, Najaye and other Building Heroes get a chance to show off and hone their skills, as well as put some money in their pocket, and also strengthen their resume and portfolio.”

Cirksey himself came to the Tiny WPA workshop through a partnership. Last spring, he participated in a pilot program sponsored by the National Street Service, a nonprofit created by Ford Motor Company with the goal of improving American streets.

He was one of 28 volunteers who, through the program, underwent training on street design, explored Philadelphia neighborhoods, and came up with a street betterment project eligible to be funded through a grant from National Street Service. The same program ran simultaneously in Boise, Idaho, and has also taken place in a few other cities.

The training in Philadelphia was a kind of “City Planning 101,” said Alexa Bosse, an architect who was a local coordinator for the program. The group spent time exploring “this idea of the soul of the street and what are those things that make a street enjoyable or not enjoyable,” she said.

One of those things is a feeling of connection to the shops and people you see as you walk along. That’s where Cirksey’s signs come in.

“Think about it — the symbolic nature of a historical sign telling the story of the beginnings of a business,” he said. “Typically a sign talks about some historical thing that happened that’s in the history books.”

“But,” said Bosse, “this is now.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.