Artists create instruments of protest in Princeton exhibit

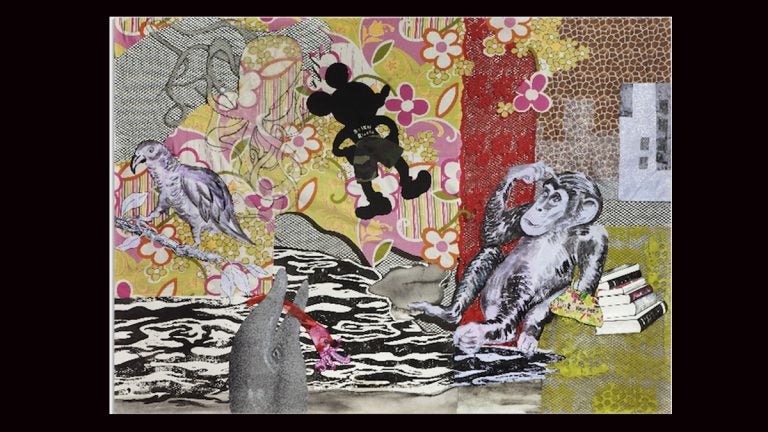

Sentience by Karen Moss

A small child with an enlarged head is on hands and knees, playing with ants. But something – a lot of things – have gone awry in this world painted by Karen Moss. The ants are supersized and a sickly green liquid appears to have flooded the land. Smokestacks billow out their last gases and dead trees are all that remain in “Aftermath,” on view in Society in Upheaval at the Bernstein Gallery, Princeton University, through March 19 with a reception March 15, 4-6 p.m.

In other post-apocalyptic views by Moss, Mickey and Minnie Mouse appear. “I’ve always loved Minnie and Mickey,” Moss says from her studio in Brookline, Massachusetts. “Disney characters are so ingrained in American culture. It’s been part of my life since childhood.”

In Moss’s “Broken Promises,” Minnie is walking away with a stack of diamond bracelets as high as the bow perched halfway between her mouse ears. This large mixed media work is painted a toxic green, a recurring color in her work. “It’s a chemical green, not what you’d find in nature,” she says. “We all dream of spring buds in chartreuse but this green is like an algae-infested lake out of control.”

At the center of the canvas, beneath the double arches of McDonalds, sits a figure in a hooded robe with a cup on the ground before him. Is he a monk, an ascetic, a Buddhist who begs? A wise holy man, or a homeless man with the same outward aura?

In contrast to the toxic green, Moss’s “Southeast Asia” is beautiful, with lovely collaged fabrics, an elephant and a tiger. But beware the illusion of beauty. This work is about the Cambodian practice of covering images of the Buddha in gold leaf, “a wasteful endeavor that bankrupts worshippers and completely obscures the actual holy image,” writes art historian Francine Miller in the catalog essay. A fashionista tiger clothed in a zebra-print dress, leggings and high heels, carrying a black fur purse, and an elephant head with tiger skin body is about the animal abuse Moss witnessed on a 2012 trip to Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. She was struck by the poverty and corruption, contrasted with gold everywhere, covering Buddhas and temples, inlaid with mosaics, as people sat on the street eating rice from bowls.

The process of beginning “Southeast Asia” began with “thinking of animals in Myanmar in danger, and the Chinese destroying forests, taking lumber from rare trees, decimating the northern part of the country where the tigers live. It’s upsetting to see jungles being destroyed, they don’t have regulations like we do here. It’s a culture clash. Without regulation you get rampant destruction of nature. I hope it can be stopped.”

Moss worked with Bernstein Gallery Curator Kate Somers to find the other two artists for this exhibit. Raúl González III, Edward Monovich and Moss share a focus on socio-political themes: social ills, environmental devastation and economic disparities.

Children in Monovich’s artwork often have the body parts of animals. “Touch Me Not” is a complicated composition of a buck-toothed girl in a wheelchair with a blue jay’s head and tail. Her arm is tattooed in what looks like dripping blood with the word “dreaming.” On the back of her wheelchair is printed “Juicy couture for nice girls who like stuff.” Meanwhile a boy in a knight’s helmet is tying her shoe, his knuckles tattooed “your next.” Within a bed of forget-me-nots and gum drops is a little pink bomb with the letters “mine.” A black drone soars overhead and a wizard-like superhero arises from the smoking chimney of an ordinary looking Dutch Colonial in the distance – the only ordinary looking thing in this world.

Monovich, who works out of a studio in his attic in Belmont, Massachusetts, also finds inspiration in the bits of ephemera he collects. These are meticulously organized into notebooks he refers to as sketchbooks. “From this imagery of war, fashion and children’s books, my crazy world evolves.”

One entire niche of the gallery is consumed with Monovich’s “They Would Rather Be Outlaws.” At center a boy walks down the front steps of a house where a bucket of geraniums sits on the brick path. That’s where the normalcy ends. His shirt has both the Adidas logo and “Fly Emirates” (the airline is a major advertiser in international soccer) and is fringed with coonskin tails. This “Davy Crocket” – for which Monovich’s 11-year-old son modeled – is crowned with a three-cornered American stealth drone. The boy holds a staff that is crowned at the top and bubble wands dangle from it – in fact the bubble wands have crowns at the top as well. The boy’s pants are not camo cloth as we know it, but printed with what appear to be mug shots… perhaps of those imprisoned at Guantanamo?

Three other works by Monovich are interactive. There are dry erase markers that viewers can use to add their own graffiti to the work. Collaborative results are photographically archived on the artist’s website. “These paintings invite conversation on controversial topical issues, while seducing participants to the edge of vandalism,” he says. “Exchanges bring fresh perspectives.”

Raúl González is a first generation Mexican American who grew up in El Paso, Texas, while spending time in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. His mixed media works reflect life on both sides of the border, from brutal street gangs and drug cartels to struggling illegal immigrants and border control officials. His satiric vignettes are reminiscent of the work of José Guadalupe Posada, the renowned Mexican artist who, a century ago, used the calavera (skeletons) to satirize corrupt politicians of his day.

So, is there hope for the future? Despite weapons and wars, and the cavalier attitude toward protecting the environment, can the earth and its creatures be saved?

“My husband and I are clippers,” says Moss. “We clip from newspapers and magazines and have vast files. While searching for inspiration, I found one article on ecology and it got me thinking: what is the relationship between how we treat each other and creatures in natural world. There is a relationship. What we do to forests and whales depends on how much justice and respect we accord each other.”

Society in Upheaval at the Bernstein Gallery, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University, through March 19 with a reception March 15, 4-6 p.m.

___________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.