Art Museum exhibits designs for both utopian and dystopian futures

The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s “Design for Different Futures” is “frenemies” with technology.

The ZXX typeface designed by Sang Mun can’t be ready by artificial intelligence but can be read by humans. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Among the 80 works on display in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s “Designs for Different Futures” show is a small glass room with two large boulders inside. Nothing about it looks particularly futuristic or design-driven.

Step inside and the point becomes immediately apparent to your nose.

The room is infused with the smell of the Falls-of-the-Ohio scurfpea, an herb that was endemic to a small island in the Ohio River in Kentucky. It became extinct in the late 19th century, due in large part to a dam built on the Ohio River. A team of biologists and scent engineers recreated what the Falls-of-the-Ohio likely smelled like, and put it in a glass box.

A project that uses technology to remember a plant that became extinct because of technology may seem like an unusual addition to a show that seems to be, by its title, about forward-thinking design concepts. But “Designs for Different Futures” is not a typical design exhibition.

“We’re trying to unpack both the word ‘design’ and the word ‘future,’” said the museum’s Kathryn Hiesinger. “Design itself has changed from the manufacture of physical objects to almost everything.”

The centerpiece of the show is a 16-foot plastic bubble in the middle of the gallery space with an umbilical cord connected to the ceiling. It’s constantly breathing — expanding and contracting — in response to the amount of carbon dioxide visitors are introducing into the space via their own breath.

Called “Another Generosity,” it has little practical value in itself. It presents as an enormous plastic bladder constantly heaving. The team of Finnish architects who designed it (Eero Lunden, Ron Aasholm, and Carmen Lee) were thinking about ways that buildings might react dynamically to natural environments.

The show is broken into 11 categories, including Resources, Generations, Earths, Bodies, Intimacies, Foods, Materials, Power, and Data.

“What makes our show different from everybody else’s with ‘future’ in the title is we posit many futures,” said Hiesinger. “It depends on who you are, where you are socially, geographically, politically.”

While one person may see the robotic baby bottle as a time-saving technology, another may see it as destroying the mother-child bond. Still another may see the small mechanical crane hovering over a crib as a symbol of how society undervalues work done by women and mothers.

“There is no paid family leave in the U.S. When people are pregnant and go into hospital, we have one of the worst maternal mortality rates in the world,” said co-curator Michelle Millar Fisher. “If you care to look deeper, you have a more nuanced understanding of what those futures look like.”

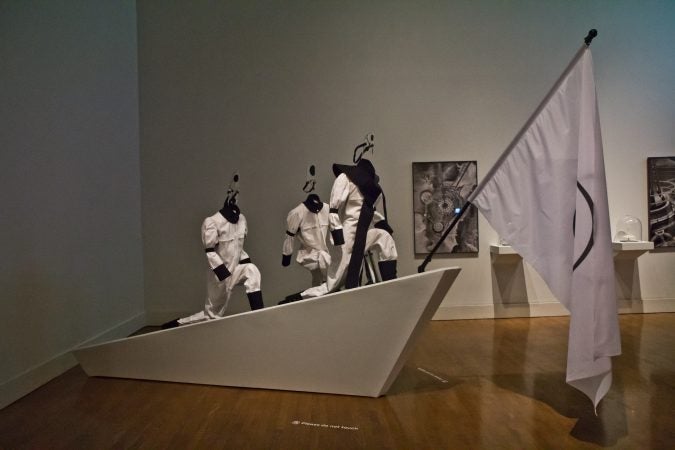

There are subversions among the pieces. A mock cooking show hosted by trans performance artists shows viewers how to make their own estrogen hormones in the kitchen, circumventing medical insurance policies. There are portraits by an artist who designs makeup, hair, and skin appliques to thwart surveillance systems with facial-recognition software.

Perhaps the most iconic piece in the exhibition is a costume from the TV show “The Handmaid’s Tale.” The red cloak and white bonnet with deep brim has since been adopted by women in street protests around the world.

Ane Crabtree designed the costume by putting herself inside the perspective of the oppressive patriarchy depicted in Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel.

“They must look ahead, and down. Any guard would be able to see if they are sharing secrets or glancing at each other,” said Crabtree. “I call it future fashion for the end of the world.”

Crabtree is originally from rural Kentucky. Her mother is a Japanese Buddhist, her father a white Episcopalian. She said her costume design came out of memories of her upbringing, a blend of nostalgic pleasure and the hardships of growing up mixed in a racially conservative place.

“When I look at it, I still get emotional,” said Crabtree, who recently visited her hometown of Henderson, Kentucky, to attend the funeral of her father.

“It’s a beautiful, fantastic place to grow up. It was safe, and surrounded by nature. This was in the ’60s and ’70s,” she said. “It’s a layered place that still has its poetry and beauty, but in the shadows lurking are the politics and conflicts hidden in this costume.”

To Crabtree, the “Handmaid’s Tale” costume has elements of timeless beauty, with the deep red and the clean lines of the cloak made of gabardine wool. Underneath, the plain dress is belted by an obi, a traditional Japanese belt, in tribute to her mother.

“Women in Gilead don’t wear makeup. They are not meant to be attractive,” said Crabtree, referring to the fictional totalitarian state in which “The Handmaid’s Tale” is set. “But [the bonnet] creates a light box, a beautiful light on their faces by the layers of linen we used.”

She is quick to point out that the outfit is meant to be a prison uniform: It conceals and isolates. The bonnets are designed to block communication. There are no pockets for hiding possessions or contraband.

“It’s a clarion call to the idea that nothing has changed for women,” said Crabtree.

“Designs for Different Futures” was created in partnership with the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the Art Institute of Chicago. It will travel to those venues after this Philadelphia premiere, on view until March.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.