TCNJ prof: ‘Art is not just a luxury for people in developed nations’

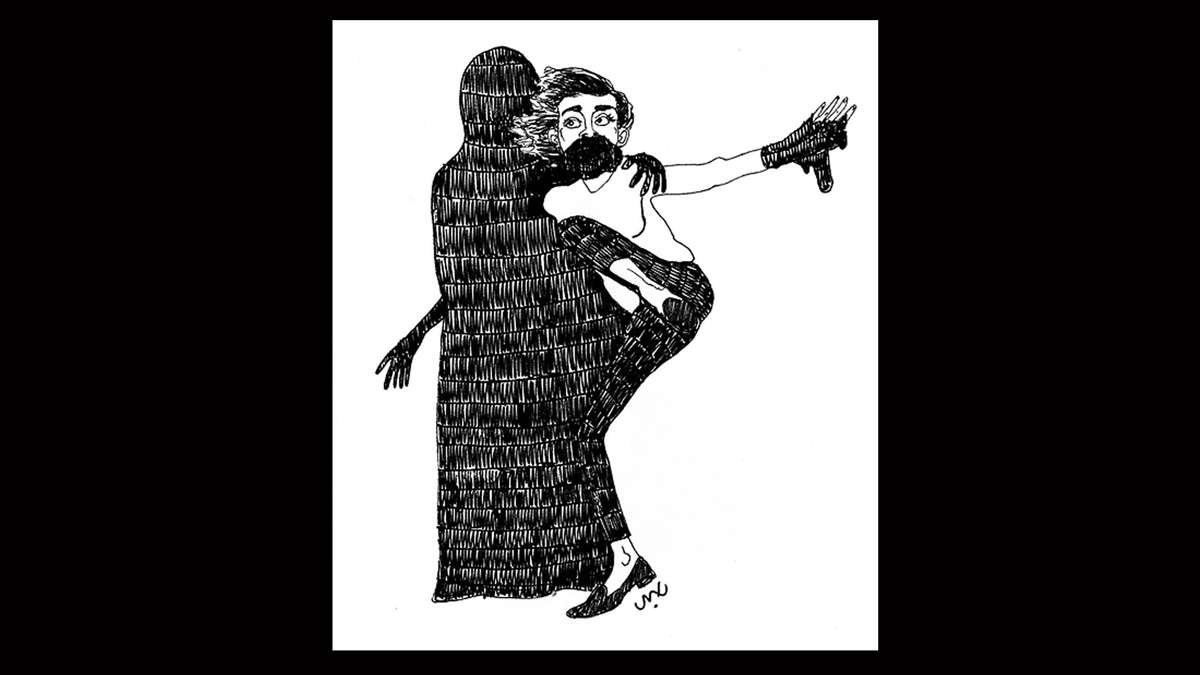

At first all we see is the black fabric. Soon a hand appears, cutting away at the cloth – there’s a woman inside, cutting through her chador, or burqa, like a chick first cracking through its shell, to create an opening through which she can view the world.

She begins embroidering; the hand, with many rings and painted nails, maneuvers the needle and thread, making the veil a beautiful work of art. After she has completed a floral tapestry on the black fabric, another hand passes scissors – the instrument by which she can escape – but she pushes the scissors back out of the hole. They drop to the floor, making a jarring sound – the only sound we hear in this video.

“Although simple and low budget, it is moving,” says Deborah Hutton, associate professor of Asian and Islamic art history at The College of New Jersey. “When I saw it, I realized that art is not just a luxury for people in developed nations, but a basic part of humanity.”

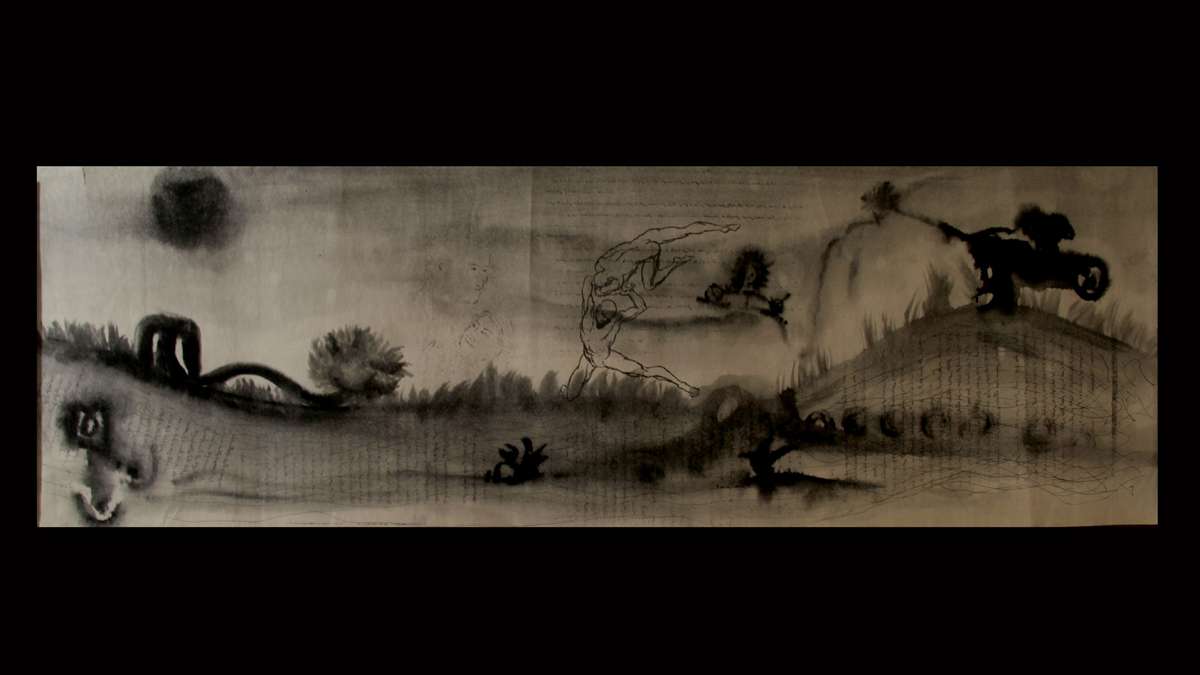

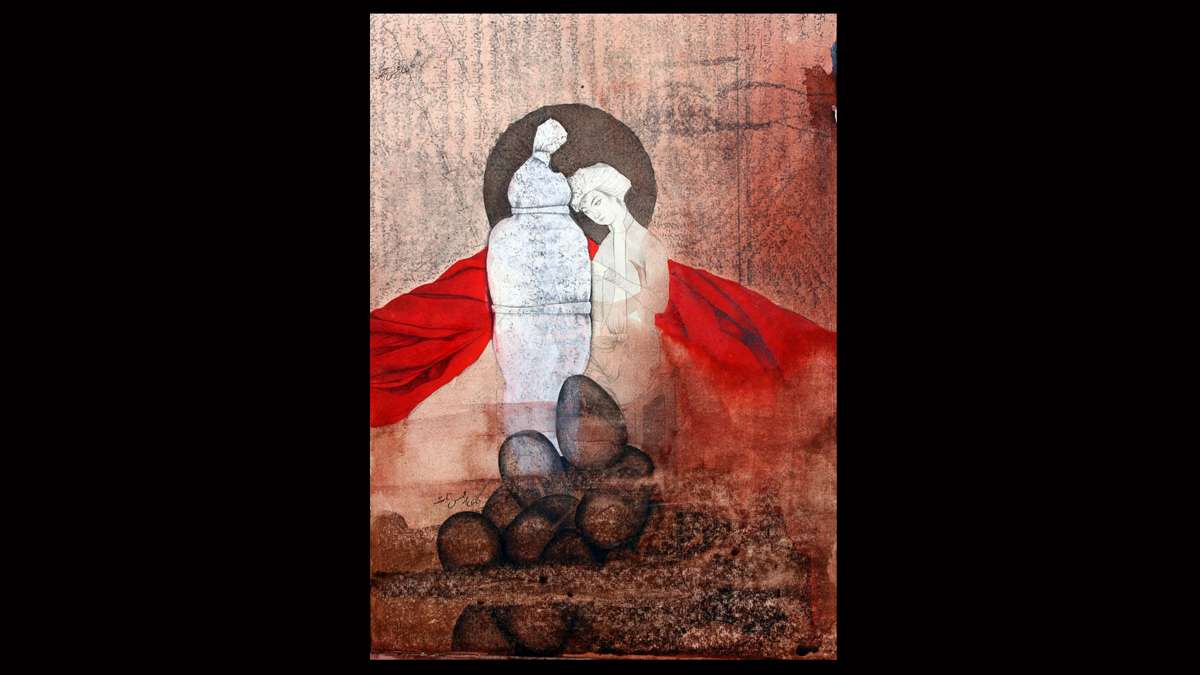

The 11-minute video by Rahraw Omarzad, who lives in Kabul, Afghanistan, is one of many treasures on view in Art Amongst War: Visual Culture in Afghanistan, 1979-2014, at The College of New Jersey Art Gallery through April 17. Curated by Dr. Hutton, the exhibit seeks to explore what a third of a century of war has done to the visual culture, and how Afghans have used visual culture to respond to the trauma of war.

It’s been 35 years since the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. Since then, the country has been in a near constant state of armed conflict or occupation, and an entire generation of adults has come of age with war as the primary experience of their country.

In 1999, the Taliban dynamited two sixth-century Buddha statues at Bamyan, following a decree that all the statues around Afghanistan be destroyed. Under the Taliban, strict interpretation of Islamic law was enforced, banning music, dance, kite flying and art depicting humans. Photography, television and film were outlawed.

Today, most Americans view Afghanistan as a war-torn, dusty, barren, cold and barren land, based on what they see in the news, says Dr. Hutton. “But as the art on display makes clear, Afghan culture survives. It has been transformed by the decades of war but has not been broken.”

Much of Afghanistan’s cultural treasures and historic monuments have been targets of destruction, yet Dr. Hutton sees hope in the growing number of young artists and photographers expressing themselves about the conflict. “While many talented photographers and artists from around the globe have created thoughtful and provocative works dealing with Afghanistan, we felt it important to show that Afghans themselves are, and have been even at the height of the conflict, using visual culture to express themselves, to provide economic relief and to record what has been happening to their country.”

In an honors seminar, Dr Hutton explored the recent history and social circumstances of Afghanistan, as well as the country’s rich cultural history. The 14 students prepared essays for the highly informative catalog accompanying the exhibition, wrote the wall text and helped to hang the show.

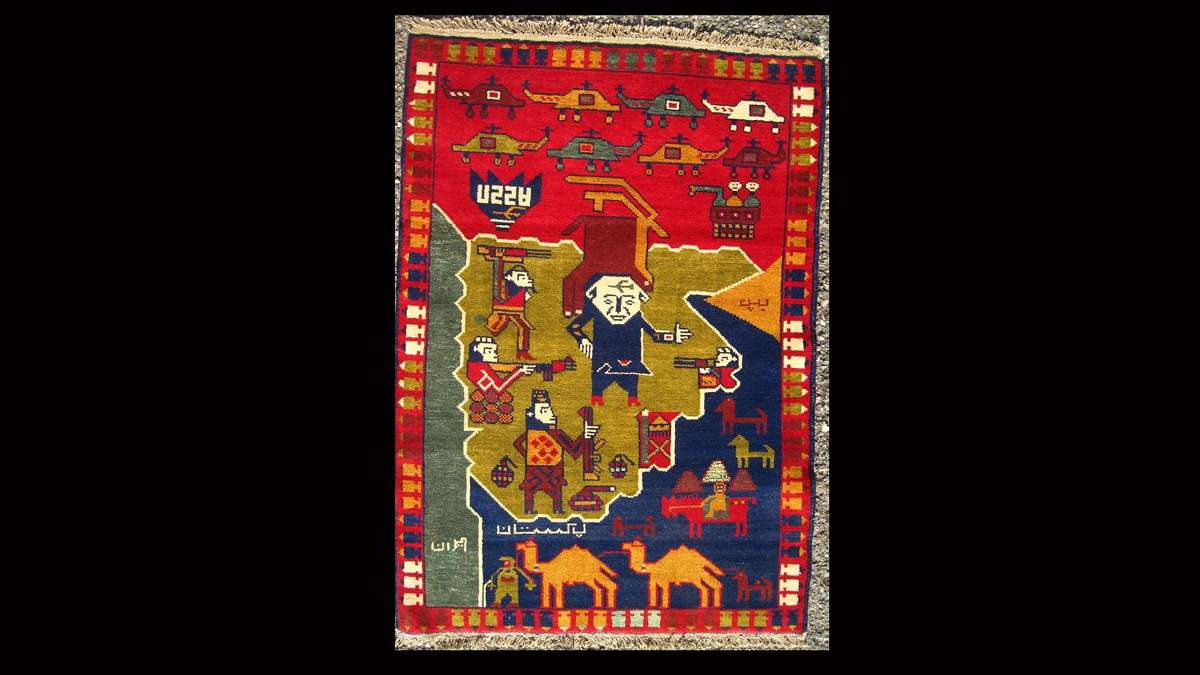

On display are “war rugs” – beautiful carpets than incorporate cars, helicopters and weapons, as well as traditional animals. After the Soviet invasion in 1979, the traditional motifs were replaced by landmines, soldiers and fighter jets, target marketing Soviet soldiers and other foreigners. After 1989, according to an essay in the catalog by student Kelly Wilson, the rugs changed, and then again in 2001, when they were made to appeal to American troops with portrayals of the destruction of the World Trade Center. “These newer rugs tout American views, rather than Afghan ones, pointing to the conclusion that they are woven only with the intent to sell,” writes Wilson.

Both rugs and posters also serve as visual aids for a largely illiterate population (years of war have destroyed the country’s educational system), warning not to touch land mines. Most tragically, Soviet-planted landmines resembling butterflies were mistaken for toys, leading to casualties among children.

For the past 30 years, Afghans have comprised the largest refugee population in the world. Displaced people fall into three categories: Those who find refuge in border countries; those who relocated to safer areas within the country (internally displaced persons); and those whose affluence carries them to developing Western countries (émigrés).

Pakistan is host to the largest official refugee populations in the world, with 1.6 million registered Afghans and an additional 1 million unregistered. They live in camps with little opportunity for education or employment. Photographs in the exhibition show refugee communities with tattered tents, residents washing clothes in pans of soapy water.

“While not flinching from showing the devastating effects of war on the physical environment, social justice, human bodies and human spirits, the works in this exhibit also reveal the constructive, creative and poignant ways in which the people of Afghanistan have and continue to respond to their tragic circumstances,” says Dr. Hutton. “There is beauty, hope and humor alongside the depictions of destruction, suffering and struggle.”

Art Amongst War: Visual Culture in Afghanistan, 1979-2014, at The College of New Jersey Art Gallery through April 17.

____________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.