Armando Sosa: Weaving dreams from Guatemala to New Jersey

The shirt Armando Sosa wears is woven in multicolored threads, predominantly bright blue. His sister sent it from his hometown of Salcaja in the Guatemalan Highlands. It is just like the garments once woven by his father and grandfather. In fact, 90 percent of the population of Salcaja made a living as weavers, although that is no longer true today.

“It’s sad,” says Sosa. “Weaving is hard physical work. A weaver works 10 hours to create a piece to sell. Older weavers can no longer continue because the materials are expensive and they don’t sell well enough for them to make a living. Younger people are not interested in weaving. They have better educations and become professionals in a different say.”

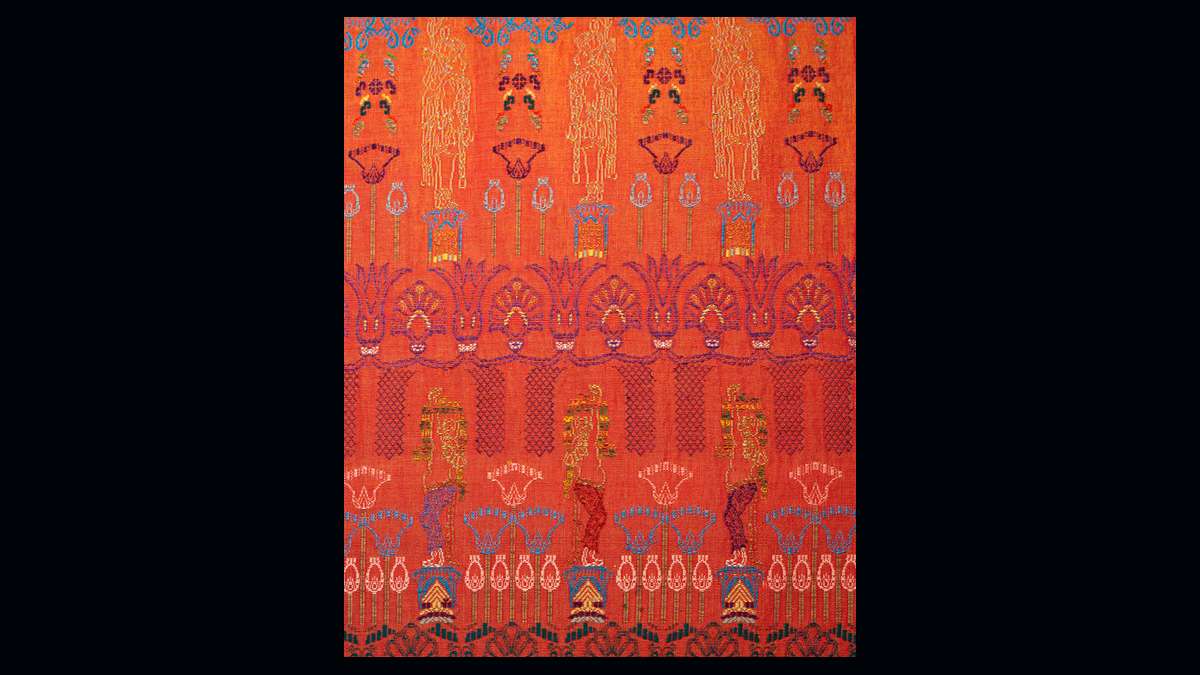

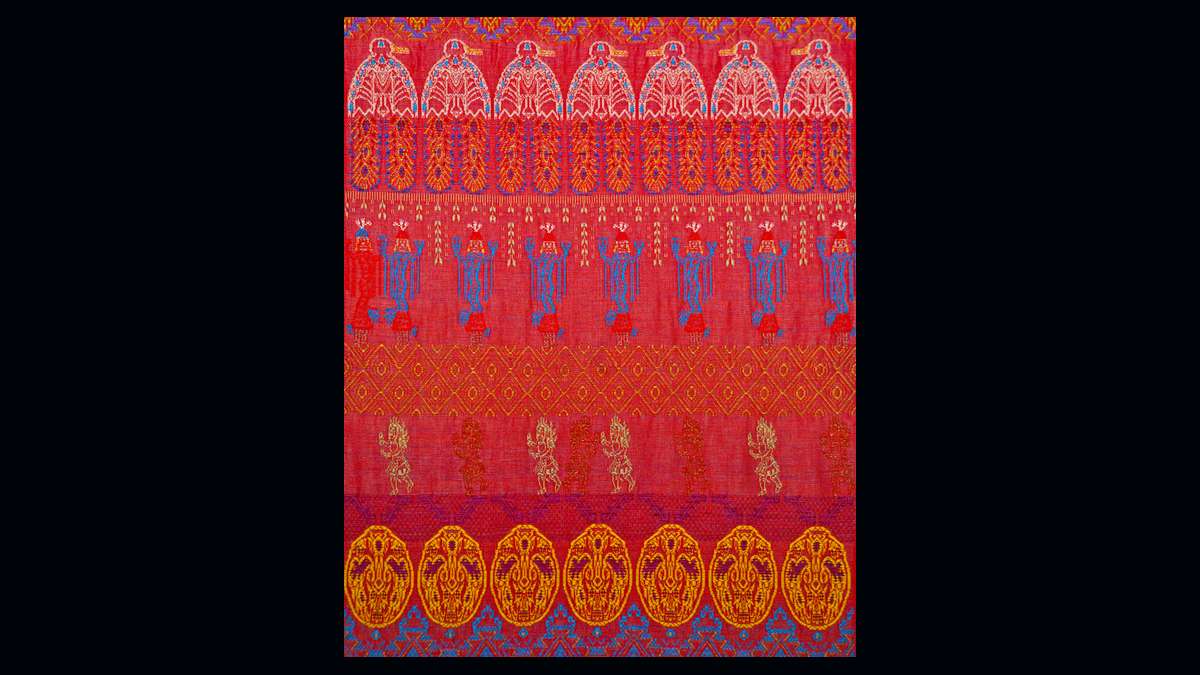

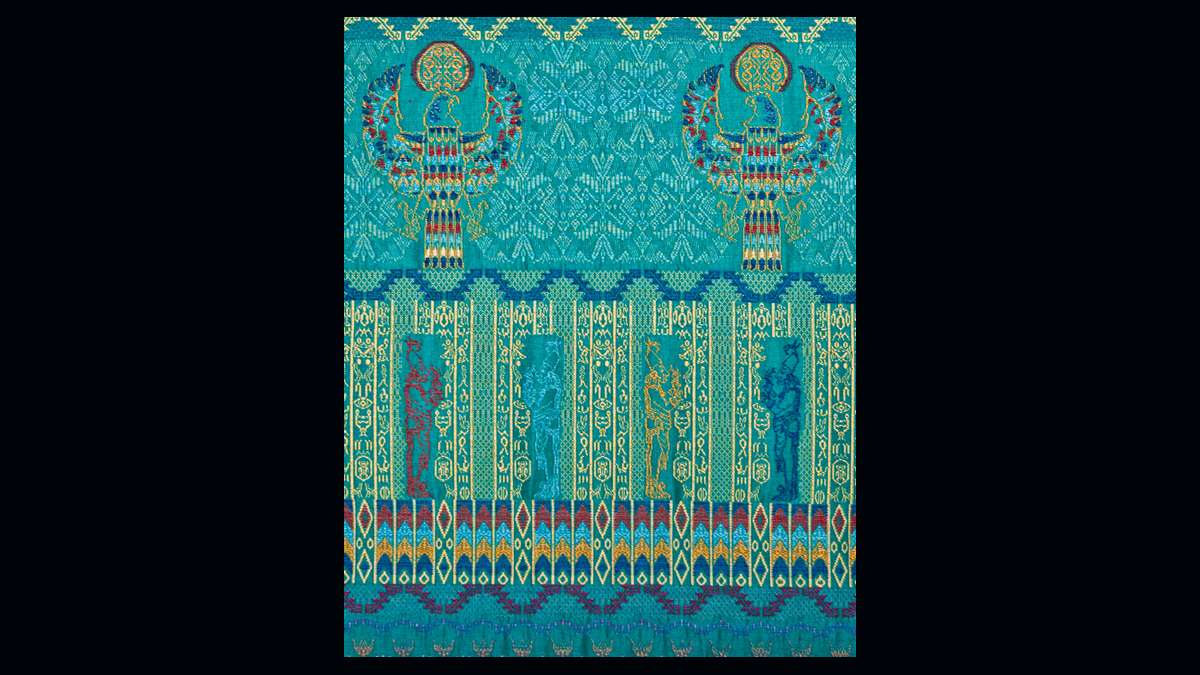

The Colored Threads of Dreams: Tapestries by Armando Sosa is on view at the Erdman Gallery at Princeton Theological Seminary through June 30. Although Sosa’s travels have taken him throughout the Americas, his tapestries are a journey around the world, paying homage to Antigua with a pattern based on European tapestries, including those by textile designer Mariano Fortuny; and Navajo, Mayan, Chinese and Egyptian designs. He finds the common visual geometry in cultural styles, a way of representing them on a complex warp and weft system. He reminds us that, long ago, people from Asia traveled to the Americas, and the common ancestries come together in his loom.

The tapestries are filled with classical motifs: turtles, lions, figures pulling fruit from a tree or trying to catch a rabbit; lotus, corn dancers. Birds and angels often float at the top. A girl jumping rope comes from a vision he recalls from childhood. The colors, he says, come from his heart.

Based on childhood memories, Sosa has built five looms since living in this country. “I believe when someone wants to do something, it’s possible,” says Sosa, giving credit to the encouragement of his life partner and artistic champion, Karen McLean, an artist, photographer and educator. In 1994, Sosa was bussing tables at Main Street Restaurant in Princeton when he met MacLean. He had observed her there on several occasions, and one day when she was leaving in the rain, he offered her an umbrella. They became friends, and he told her how he loved to weave.

Sosa’s childhood was cut short by the need to work at an early age. His mother, who worked with his father, passed away when Armando was 9. His four sisters worked, helping in other people’s houses. At 14, Armando went to help an uncle, learning to weave shawls to sell in the market. He wanted to study, but there was no night school in the small town. When he was 15, he moved to Guatemala City where an older sister lived, helping out in a house where he was given space to stay. By the time he was 16, to pay his rent, Armando washed cars for 50 cents a day. “But that barely paid for my lunch and bus fare.”

Soon he found work in weaving again. In 1970 he was sent to a state fair in Dallas, Texas, to demonstrate weaving. “It was my big opportunity to see the world,” he says. He stayed for a month, then returned to Guatemala, selling handcrafts. In 1973 and 1974, and again in 1979, he returned to do demonstrations at state fairs on the West Coast. Through the demonstrations, “I learned what people liked about colors. It embedded in me the idea that someday I would make my own weavings.”

Sosa wasn’t able to return to the U.S. for 13 years. In 1993, he had an opportunity to come and stay.” Soon after moving to Princeton, Sosa made an overnight trip to Pittsburgh and saw a window display in which a weaving was used as art, not a functional item, and he realized this was what he wanted to create. It was a turning point.

Sosa worked at Davidson’s Supermarket on Nassau Street, cleaning and stocking shelves. Even with his work in the collections of the Newark Museum, Princeton Public Library, Johnson & Johnson World Headquarters, University Medical Center at Princeton in Plainsboro, Capital Health Systems and Dr. Oye Olukotun, among others, Sosa works as a framer to earn a living.

For the past eight years, he has worked at the Framesmith Gallery in West Windsor. He credits owner Paul Smith as another champion of his work, and for connecting him with Sharon Hubert who arranged for this exhibit at the Erdman Gallery. It was through his framing experience that Sosa learned how to hang his tapestries, using two dowels for support. The weight of the lower dowel helps to keep the tapestry flat.

As an artist, Sosa is largely self-taught. After finishing primary school at night, and then five years of secondary school in two years, he studied English at the American School in Guatemala and took correspondence courses in marketing and management. He studied administration and accounting at San Carlos University in Guatemala City, but learned about art through McLean’s art books. His sense of color, too, comes from McLean’s studio. “I am inspired by the colors I see and want to combine them.”

Interestingly, this weaver is allergic to wool, so all the tapestries are made from cotton and silk. He sources the fine threads from former textile factories and from a sister in Guatemala.

All his life, hard work is what Sosa had known. But when he weaves, the outside world doesn’t exist. In that state, he returns to the world of his childhood, hearing his father whistling songs he heard on the radio and his grandfather talking to his grandmother.

The Colored Threads of Dreams: Tapestries by Armando Sosa is on view at the Erdman Gallery at Princeton Theological Seminary through June 30.

____________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.