Archive of ‘male physique’ photos pose problem for Willow Grove auction house

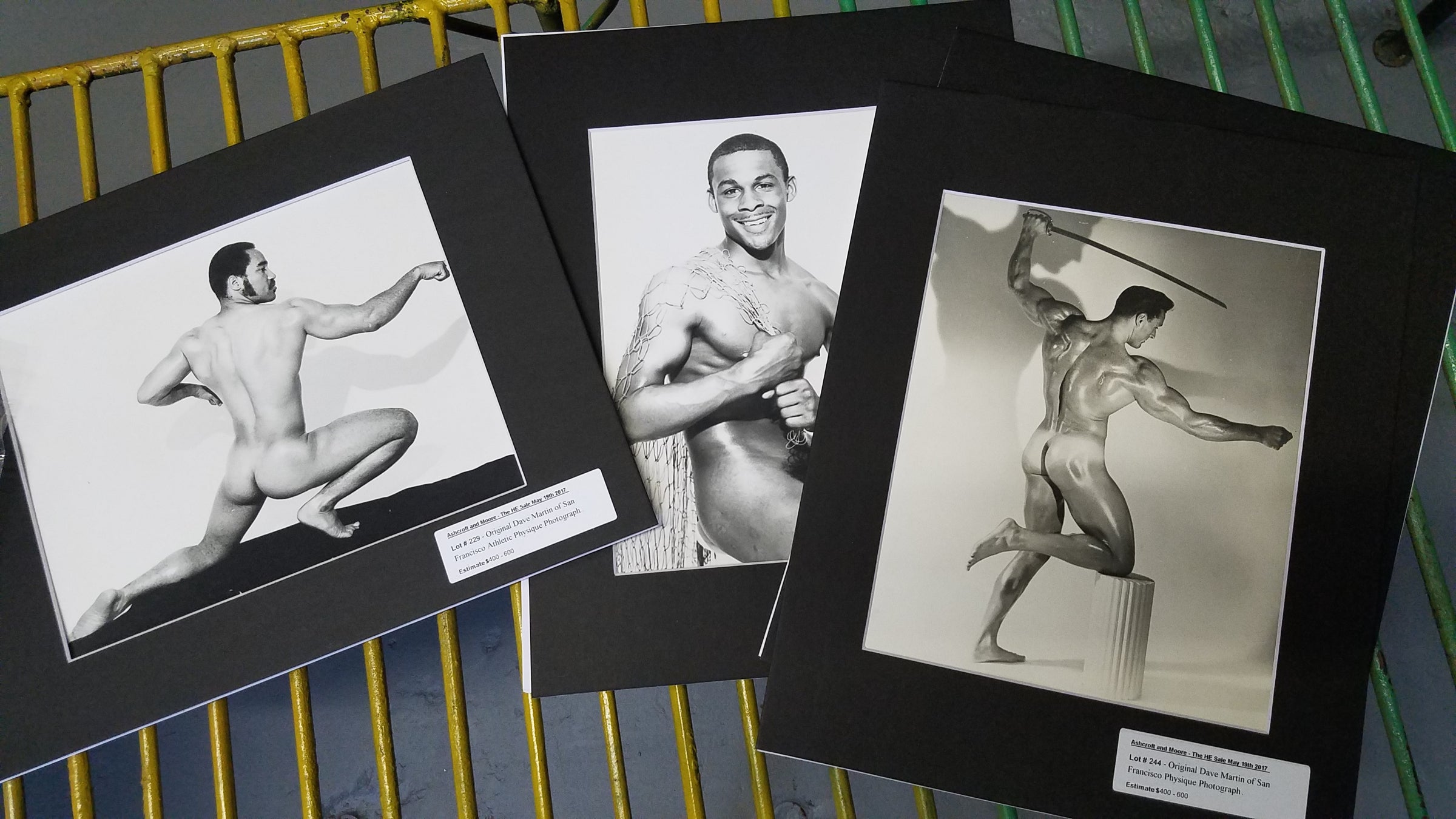

A sample of vintage prints by Dave Martin that will be auctioned Friday.(Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

Ashcroft and Moore, a new auction house about to stage its first auction, is situated in an unassuming warehouse space on Fairhill Road in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania.

The owners have not yet hung a sign on the building, so it’s nearly impossible to find. Inside, the space is already crammed with items to be auctioned off in upcoming sales. There are no chairs set up, nor a podium. Like most auction houses these days, most of its sales will be online.

“Auctions these days don’t have folks in an audience, with leather patches on tweed jackets, holding paddles,” said co-owner Alexander Stanku. “It’s the opposite. People would rather sit home in their underwear in front of their computer and bid.”

Stanku is running Ashcroft and Moore with a unique business model, one that might seem risky to traditional auction houses — he is eliminating the buyer’s premium. When you place the winning bid on a lot at auction, most houses will tack on an extra 20 to 30 percent. That means, if your $400 bid wins a painting, you might actually pay $500.

It’s not a hidden charge. The buyer’s premium is stated up front when you register for an auction — it’s how an auction house makes a profit. But Stanku believes it scares away would-be bidders, particularly younger people who are new to auctions. He is gambling that a 0 percent buyer’s premium will attract more bidders, thereby driving the bids higher, benefiting the seller’s return and Stanku’s commission.

That is, if he can get started.

‘Beauty of the male physique’

Stanku had to delay his inaugural auction for three weeks to deal with censorship from his advertising platforms. Finally, on Friday, he will begin selling the photography of Dave Martin.

“Some people may just see pictures, but there’s a story here,” said Stanku.

Dave Martin was born in 1923, in Haverford, Pennsylvania. As a young man, he taught himself photography and moved the San Francisco, where for 30 years he specialized in “male physique photography” — young, muscular men in athletic poses, nearly or completely naked.

He sought out college athletes and military men to pose for him unclothed, then sold the pictures to subscribers, mailing packets of prints directly to his customer base. He was known as Dave of San Francisco, part of a generation of photographers (i.e. Bruce of Los Angeles, Douglas of Detroit, Lon of New York) famous in the mid-century, gay underground for taking quasi-erotic “beefcake” photographs.

There was significant risk in this; in the 1950s, the U.S. Postal Service did not allow the distribution of anything that appeared to be homosexual imagery. Studios could be raided and photographers arrested, their negatives destroyed. Martin, himself, spent some time in jail.

Since Martin died in 2014 at 91, his photographs have become collectible. Vintage prints (those printed by the photographer at the time the shots were taken) can fetch a few hundred dollars apiece, significantly more if they are signed. Surviving vintage prints by photographers whose work was destroyed can sell for thousands of dollars.

Because many of his models were student athletes at Stanford University, its Special Collections Department accepted a large part of Martin’s archive. Martin, who was still alive at the time, added a written note of explanation to the Stanford librarians: “My work consists of photography heterosexual (straight) men active in athletics and to show the beauty of the male physique. It is not a Gay Archive [emphasis his].”

Though not explicitly sexual or gay, the images are suggestive, particularly to their likely audience who would have had a wink-and-nod understanding with Martin.

“Looking closely at the attention given to certain body parts, body images, and certain physiques, you would have to gather that this is not something that would be on the coffee table at home,” said Stanku. “That element is assumed, maybe rightly so.”

Qualms over content

After Martin died, his family in Haverford assumed his papers and archive, and made a deal with Ashcroft and Moore to auction them off. Stanku prepared a catalog of more than 300 images — most of them Martin’s, adding more male nude photography, drawings, paintings, and sculpture from other collections — for the “HE Auction.”

He then went about posting the catalog on major auction websites, on whose portals the sale would take place.

Almost immediately, one portal blocked the catalog. While agreeing to run the sale on its site, the images being auctioned would not be viewable.

“We got an email from the portal, that our sale would be a white-label sale,” said Stanku. “The only way people could view it is if we directed them through direct-email links. Much like the subscriber service Dave Martin had to do to find interested people, that’s what we would have to do, too.”

Stanku pushed back the auction date in order to negotiate with the online portal (which ultimately agreed to run the images) and rebuild advertising for the sale event.

Then a second blow: Facebook refused to run his sponsored ads. Stanku had to recrop the images in his ads to appease Facebook’s decency standards.

All of which blindsided Stanku, who says these images from a half-century ago show the aesthetic sensibility of a subculture from a chapter of American history.

“Institutions take them. This represents a period of time,” he said. “There’s a value in that time frame of photography.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.