After 2008 financial crisis, only one bank faced criminal charges. Why?

Listen

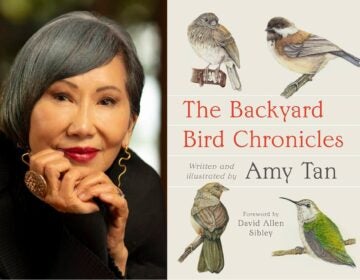

The Philadelphia Branch of the Abacus Federal Savings Bank on North 10th Street in Chinatown. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Only one bank faced criminal charges after the 2008 financial crisis. It’s not a big one like JP Morgan Chase or Citibank, it’s a small family owned bank in Chinatown in New York, with a branch in Philadelphia.

A new documentary playing in Philadelphia next week tries to answer the question: why this bank?

Abacus Federal Savings Bank isn’t like other banks, says president and CEO Jill Sung.

“We know from first hand experience that customers like ours get summarily kicked out of larger institutions every couple years when the large institutions decide that this…kind of customer is not profitable,” she said.

It serves primarily Chinese-American immigrants, so it’s a little different.

For instance, they still have a type of account called a passbook savings account. That’s where the customer carries a passbook with them. Deposits and withdrawals are stamped on the book, so you have to do your transactions with an actual person.

Sung says most large banks don’t offer those accounts anymore.

“We need to maintain that still because we have a large sector of our population who are still using those passbooks, we can’t turn our backs and say well don’t use those anymore,” she said.

Abacus understands the cultural differences between most US banking customers and the Chinese immigrants it serves. For instance, she says immigrants from China are familiar with an authoritarian government.

“It creates a kind of fear and distrust under people who live under that regime, towards government in general,” Sung said. “Like even FDIC insurance, they may not understand what that means, like why would the government back stop every single insurance up to $250,000.”

In 2012, when the New York County District Attorney indicted the bank for mortgage fraud, the Sung family was confused.

Not because of the fraud, they knew about that.

Back in 2009, they found out one of their loan officers was lying on mortgage applications, but they had already fired him, done an internal investigation, and shared their findings with regulators, the police, and the DA’s office.

And of course the mortgage crisis implicated many banks, so why go after this one?

First of all, Abacus is a small bank. The New York Times reported in 2011 that officials were worried about aggressive prosecution threatening an already fragile financial system.

Jill Sung says it’s also “pretty transparently clear that race bias against Asian Americans, Chinese Americans played a role.”

“We saw it in the way they approach the case, we saw it in the way they approached their witnesses, we saw it in the way they approached our employees,” she said.

She points to one instance, when the DA arrested some bank employees very publicly.

“Eight or nine of our former employees, who they decided to arrest, was linked by chain together and forced to walk through a row of media cameras,” she said. “Most of them in that chain were women and at least one or two of them were grandmothers.”

Her sister and bank director Vera Sung says this is a stark contrast to how suspects are normally treated.

“Normally people take painstaking measures to cover the handcuffs with a coat or folder or whatever because once you see handcuffs on somebody, you automatically now think they’re guilty,” she said.

Colorado theater shooter James Holmes wore a hidden harness for his trial in 2013, and part of it was disguised to look like a computer cable. His lawyers argued that if he were shackled during the trial, he would look guilty to the jury.

In France, it’s illegal for media outlets to show suspects in handcuffs before they’re convicted.

New York district attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. declined to comment for this article, but in the movie, he says the public arrest was “very unfortunate” and can “create feelings that…don’t reflect the view of the office.”

A documentary about this case, “Abacus: Small Enough to Jail,” will be showing in Philadelphia for a week starting June 16 at the Ritz at the Bourse. It’ll be in more theaters nationwide afterwards.

Jill Sung says since the movie came out, people have been telling them about many more stories of racial bias against Asian-Americans. She lists notable examples like Army private Danny Chen who was pelted with rocks and taunted with ethnic slurs by fellow soldiers, and a Chinese-American physics professor at Temple University who was falsely accused of being a Chinese spy.

“We have to start stringing these together and use them to move forward, they’re not isolated,” she said.

Vera Sung says that during the trial, she couldn’t help thinking what it would have been like if they hadn’t had access to lawyers.

“I’m a lawyer, my sister’s a lawyer, my father’s a lawyer, my other sister’s a lawyer” she said. “There’s many people who are innocent who decide to be brave enough to stand trial, and I was thinking, how do they handle it?”

The Sung sisters say that going forward, they’re going to make sure everyone in their community knows their rights, and votes.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.