A rent-to-own project spurred dreams of homeownership in Chambersburg. The reality leaves tenants feeling ‘set up to fail’

An effort to bring affordable housing to Chambersburg, Pa., promised to help tenants become owners. But the reality is much more complicated.

Listen 5:05

Jonathan and Marcia Pretlow with their children, Julius, Asia, and Laila. (Dani Fresh for WHYY)

Jonathan Pretlow dreams of having an asset that will help springboard his family forward for generations. As is the case for many Americans, that means owning a home.

In 2010, his then-fiance Marcia moved from Baltimore to join him in Chambersburg, a borough of around 20,000 in central Pennsylvania. Their blended family — two kids of hers, one of his — moved into a neighborhood of two-story townhomes billed by local officials as a “rent-to-own” project for low-income residents.

The Pretlows began paying rent for their Redwood Park home with the understanding that they would take on the mortgage after 15 years.

Such an opportunity “almost felt like a prayer being answered,” said Pretlow, who works at Letterkenny Army Depot, a Department of Defense facility just outside the borough.

In newspaper articles from that year, the building developers and community leaders hailed the project as transformational.

“Our intention is to turn these into a homeownership opportunity” with an aim to make the neighborhood “vibrant again,” said Charles Scalise, former CEO of the nonprofit developer, in one 2010 article.

“The community said, ‘This is what we want. We want affordable homes,’” said Jack Jones, a neighborhood development manager in Chambersburg, in the same piece.

Fewer than half of Chambersburg residents own their homes, compared to 71% in Franklin County as a whole, per the U.S. Census Bureau. About one-third of Chambersburg residents are Black or Latino in a county that is 92% white, and the poverty rate in the borough is also higher, according to federal data. Officials promoted the Redwood Park Townhomes project as a way to add more affordable housing, with the promise of turning some renters into owners.

But as the last decade went by, Pretlow and other tenants in the 40-unit development became frustrated by the lack of clarity in the terms of the agreement. For the past three years, they have been asking questions about exactly how the transition to homeownership would happen, and what would be required of them, but said they haven’t gotten firm answers from the property management group.

“I think we’re being set up to fail,” said Marcia Pretlow. “[In] four or five years, you know, they’ll just say, ‘Oh, well, you guys don’t qualify to own this home.’”

A lack of information and communication drove these fears. Community residents said their questions received vague answers, and they did not know where to turn to for help.

Through public records requests and interviews with experts, Keystone Crossroads learned that the underlying terms of the residential community are more complex than a typical “rent-to-own” program. The development was completed with the help of a bailout during the Great Recession meant to increase affordable rental housing in the area. The lease-purchase part of the deal turns out to have been a secondary goal and the document laying out how that would happen is not legally binding.

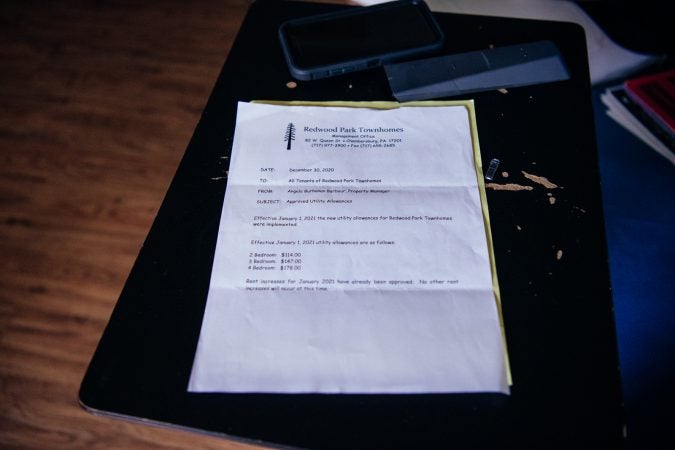

The project also differs from traditional rent-to-own agreements in a key way: The rent tenants pay builds no equity towards a down payment, a fact many residents said they did not know until a meeting with a property manager in November 2020.

“We had no idea,” said Pretlow.

For its part, Luminest, the property management company, said it did not have all the details either.

“We were only ever able to tell them that we were aware that after 15 years, the homes would be available for home ownership,” said Bonita Zehler, executive director of Luminest. She said tenants were expected to take advantage of low rents to save on their own.

After continued pressure from the tenants, Luminest pointed residents to the Erie-based Housing and Neighborhood Development Service (HANDS), one of two groups that own the development. When Luminest reached out to HANDS earlier this year with some tenants’ concerns, they received a letter in response.

The property managers shared the note with residents, who said it felt like a brush off.

“Questions about the project conversion and option to purchase individual units at Redwood are premature,” said Matthew Good, CEO of HANDS, in a letter dated March 2, 2021. The note also contained a list of factors that would ultimately weigh on the prospect of homeownership, saying there would be creditors to please and legal hoops for the owners to jump through.

“Residents must understand that it’s not up to Luminest or solely HANDS, whether the option to purchase will be available” at the 15-year mark, Good continued.

This ongoing uncertainty floored not only some of the original tenants, but local elected officials who had championed the development as well.

“The borough at the time was proud of this development, and was proud of the concept that it was rent-to-own,” said former Chambersburg Mayor Peter Lagiovane. “I was shocked when I heard there seems to be an issue coming up now.”

“I just want a straight answer,” said Alexander Houser, 33, another long-time tenant at Redwood Park. When he moved in a decade ago, he was thrilled to be able to live on his own and afford a new home on his $9/hour salary. At the time, he said his rent was about $600 a month.

Since then, he started a family and found higher-paying work. Houser said he is ready to become a homeowner, and understanding whether to keep renting the same place is a crucial decision.

“We’re just trying to figure out what to do with our lives right now,” said Houser.

The red tape

These practical concerns run smack dab into the reality of Reagan-era public policy that’s not actually intended to increase homeownership.

The Redwood Park Townhomes received federal support in the form of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, or LIHTC.

Created in 1986, these tax credits are now the single biggest engine behind building affordable housing in the United States. Since its inception, the program has funded the construction or rehabilitation of more than 3.2 million housing units across the country, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Here’s how they work: The federal government doles out the credits to states, which then require developers to compete for them. In Pennsylvania, only about a quarter of projects that apply for LIHTC funding get approved, according to the state’s Housing Finance Agency.

Developers who win still don’t get money — yet. They get tax credits, which they then sell to large private investors, who use them to reduce the taxes they have to pay on other investments. The money from that sale ultimately finances construction.

The Redwood Park Townhomes got this far when the Great Recession hit. Instead of being able to sell the tax credits, the developers sought a bailout through a special stimulus program created by the American Recovery and Restoration Act of 2009.

All of the same red tape as LIHTC still applied. Once the homes or apartment buildings are completed, federal law requires that rents be kept low for years, or decades, to fulfill the promise of providing affordable housing. Proponents say the program combines the best of the public and private sector, while critics argue that having so many middlemen involved is inefficient.

Most of the time, the process ends there. Adding on another transaction and converting tenants into homeowners “is highly, highly unusual,” said Carol Galante, faculty director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California, Berkeley.

“You generally can’t use the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit on anything but a rental property. And so these folks are renters for a much longer period of time,” at least 15 years, in order to satisfy the terms of the tax credits, continued Galante. She said that’s much longer than a more typical rent-to-own arrangement.

Still, the promise of getting two benefits — affordable rental housing and increasing homeownership — out of one stream of government funding has enticed nonprofit developers to try it. There are 19 such developments around Pennsylvania, according to PHFA, but in each case, the option to sell a property to low-income tenants after 15 years is just an option, not a requirement. HANDS is involved in several other lease-purchase developments around the state, according to its CEO.

Experts point to CHN Housing Partners in Cleveland, Ohio, as the industry leader of this type of program.

Since 1987, that organization has helped 1,350 people become homeowners in the Midwest through lease agreements, according to CHN’s website. Around 99% were still living there after five years.

CHN declined to talk on the record for this story, but sources familiar with the organization’s model spelled out some of its principles. At the 15-year mark, the home sale prices are kept very low, often around $20,000. Before that time, tenants are called “residents” in order to emphasize their path to homeownership. Instead of needing good credit, CHN requires three years of on-time rental payments to assess ownership readiness. The group also provides financing in-house. Transparency with residents is key.

This level of support is needed to overcome the barriers to homeownership that low-income Americans face.

Only low-income tenants can rent in Redwood Park, and most have incomes somewhere between 20-60% of the area median, according to Zehler.

Bad credit, lack of savings for a down payment and closing costs, and unfamiliarity with the process can all be barriers to homeownership.

Only around half of households making less than the median income own homes, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. At the end of 2020, the rate of homeownership among the Black and Latino communities in the country was 44.1% and 49.1% respectively, well below the national average of 65.8%.

“For folks who may not qualify for a mortgage, they may view these rent-to-own agreements as their only possible path to homeownership,” said Michael Froehlich, a housing attorney with Philadelphia-based Community Legal Services. “Sometimes they are successful, but people should be well aware of their rights and the risks that are involved.”

The answers

About six weeks after HANDS sent the letter saying discussions of conversion were “premature,” the group provided a plan for transferring ownership to tenants, in response to repeated questioning by Keystone Crossroads.

“HANDS is committed to the obligations in the original funding application and regulatory documents to provide a homeownership option to the residents of Redwood Park who are interested and qualified,” wrote Good.

The development is predicted to have around $860,000 dollars in debt after 15 years, the earliest units could be sold, according to Good. The estimated cost for tenants to purchase, based on how much debt is left right now, the need for maintenance, and to set up a homeowners association, is $75,209. That’s well below the median home price in Chambersburg, which is $204,031, according to the real estate listing site Zillow.

Any tenant who qualified to move into the development based on their income, whether it was in year one or year 14, can apply to become a homeowner, provided they complete a mandatory homebuyer counseling program and qualify for a mortgage. Good said HANDS will kick in $1,000 towards closing costs.

David Uram, the CEO of PIRHL, the other housing developer involved in building the Redwood Park Townhomes, stressed how difficult structuring these deals can be, and called not discussing the terms with tenants sooner a “blindspot.” Uram said to his knowledge, the tenants were never told their rent would go towards a down payment or equity.

“I think it’s absolutely amazing that some of the residents have been there that long and maybe that’s a tribute to the project, but we probably ought to start facilitating some communication,” he said.

Keystone Crossroads shared this information with some tenants who hoped to own their townhomes.

One reaction was sticker shock.

“That’s a lot of money still,” said Alexander Houser, who said he was disappointed that years of paying rent did not add up to something concrete attached to his name.

He also repeatedly questioned the way the development had been framed at the outset, saying, if it’s not really rent-to-own, “why was it labeled this way?”

For the Pretlows, finally having the information they sought puts their situation in focus. Over 10 years, they spent more than $85,400 on rent, payment records show. Their kids, who were in elementary school when they moved in, are now nearing college, and decisions about tuition are due soon. Now, they would need to take out a mortgage for tens of thousands of dollars to own the house.

The payment estimate is “a kick in the gut,” said Jonathan Pretlow, but the lack of anything in his name was worse. “When you go into homeownership, that’s pride that you take. That means, ‘I’m the king of my castle,’” he continued.

“I’m disappointed,” said Marcia Pretlow. She questioned why $30,000 of the estimated sale price was needed for repairs and to fund a homeowner’s association, expenses they would again be expected to bear, but which would be out of their control.

Both Jonathan and Marcia Pretlow said they are grateful for aspects of the Redwood Park project. The low rent is a boon, and the amount of space a blessing with so many teenagers in the house. They have spent years envisioning how they would make the place theirs, like finishing the basement or installing ceiling fans through the house, modifications barred to renters.

If they had known all of the terms from the start, they say they might have made different choices. But after so much time, Jonathan Pretlow said he would like to stick it out, if only on principle.

However, they won’t soon forget the feeling of being unheard and in his words, “talked down upon.”

“The only time people make any reaction is when somebody else speaks up for us,” he said. “Hey, don’t you see me? We’re worth something. We live here. We’ve invested.”

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

Get more Pennsylvania stories that matter

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.