A dance on the avant-garde side: Philadelphia exhibit honors five artistic visionaries

-

Margaret Leng Tan prepares a piano at the Philadelphia Art Museum for a performance of John Cage's music for film. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

A school group at the Philadelphia Art Museum stops to watch and listen as Margaret Leng Tan prepares a piano for her performance of John Cage's music for film. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Margaret Leng Tan consults the instructions for preparing a piano for a John Cage Competition. Bolts, screws, and bits of wood and rubber are arranged among the strings. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Bolts and screws of various types and sizes, pieces of wood and bits of rubber are arranged among the strings of a grand piano at the Philadelphia Art Museum according to composer John Cage's specific instructions. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

John Cage's music for prepared piano gets its unusual sounds from objects placed between the strings. Margaret Leng Tan prepares a piano at the Philadelphia Museum of Art before her performance of Cage's music for films. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

In addition to ordinary musical notation, John Cage's piano score includes instructions like "water glistening" and specific instructions for placing objects between the strings. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

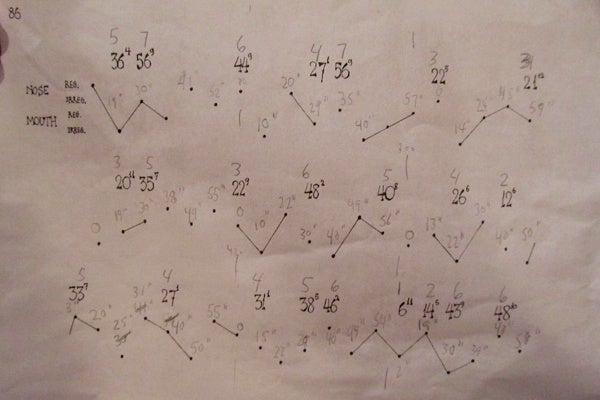

<p>Bhob Rainey of The BSC performs John Cage's "Songbooks#22" — Regular and irregular breathing, inhaling or exhaling as necessary, through the nose and mouth. Regular means even or changing gradually. Irregular means uneven and changing abruptly.</p>

-

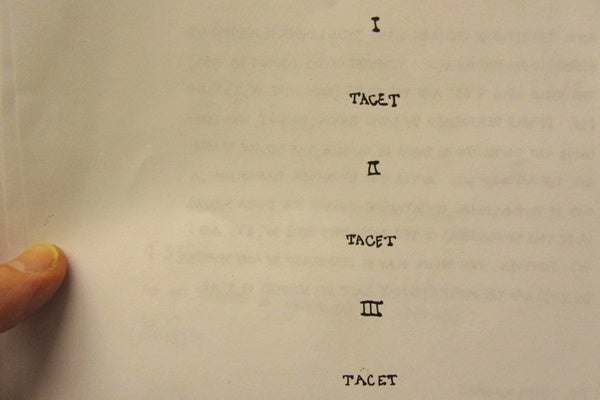

<p>Sheet music for John Cage's "4'33"</p>

-

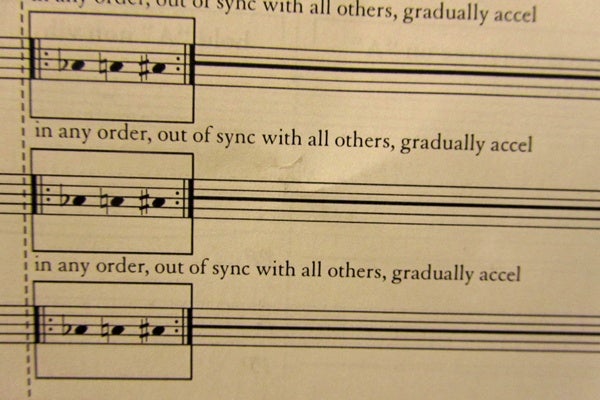

<p>Sheet music for David Ludwig's "Fanfare for Sam"</p>

-

<p>The notations for John Cage's "Songbooks#22": Large numbers relate to the number of dials (electronics). Smaller numbers indicate position of dial. Begin with arbitrary setting, including off.</p>

-

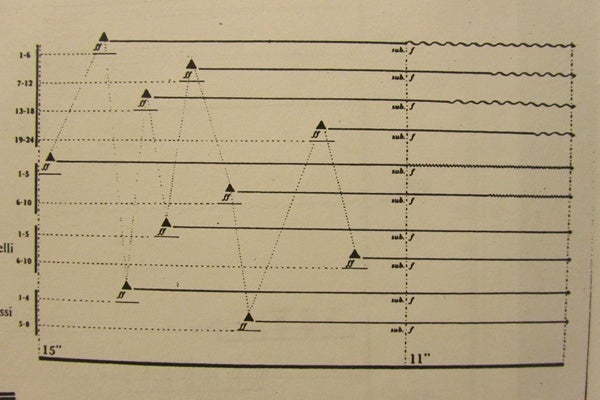

<p>Sheet music for Krzysztof Penderecki's "Therondy to the Victims of Hiroshima"</p>

With five of the 20th century’s most radically progressive artists, it’s little wonder “Dancing Around the Bride: Cage, Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenberg, and Duchamp” is as cacophonous as its title.

Each of them — John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Marcel Duchamp — shook their respective fields down to their bones, spinning dizzying head games out of the question(s): What is art/dance/music?

On entering the main hall of the Philadelphia Museum of Art exhibition, the show resembles a circus, with objects wrapped in balloons suspended over a large platform on which dancers perform regularly throughout of the run of the show (until Jan. 21). Paintings and sculpture line the walls, and a glossy black piano — prepared with bolts and rubber on its strings — is on a transparent Plexiglas podium playing dissonant, sometimes random, notes composed by Cage.

The sound of the exhibition does more than color and complement the art. As a fifth of the title, Cage’s pieces are presented with equal presence. The sound assaults the viewer as strongly as the cracked bride around which this exhibition dances, Duchamp’s “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass).”

There are 43 speakers distributed throughout the show. Works by Cage and Duchamp scamper and flit between them as the sounds move around the room.

“Maybe elicit feelings of fear, or the beauty of the piano notes that are muted or plunked. It sounds like a piano, but maybe it isn’t,” said sound designer Duncan Edwards. “Or, if it’s the voices of [Duchamp’s] ‘Erratum Musical,’ you would wonder what exactly are they saying? And why are they moving?”

A celebration of Cage

Concurrent with the exhibition is a three-month festival of performances of Cage’s compositions called “Cage: Beyond Silence,” co-produced by the art museum and Dustin Hurt of Bowerbird, an experimental-music presenter.

It features concerts by artists who were the avant-garde with Cage in the mid-20th century (Pauline Oliveros, Christian Wolff), who worked closely with Cage (Margaret Leng Tan, Laurel Karlik Sheehan), and the generation that received his legacy (The BSC, The New Music Network).

Cage celebrated chance sound, advocating that noise could be received as music. Compositions were often very loose. He would determine which notes to write down based on the throw of dice — the I Ching. He would lay tracing paper over maps of outer space and put notes where the stars were.

Sometimes he did away with staff and notes altogether, composing by simply writing out a few sentences of instruction. This is how to perform “0’0″” from “Songbooks”: “In a system provided with maximum amplification, no feedback, perform a disciplined action. With any interruptions, fulfilling an obligation to others, no attention to be given the situation.”

Some of Cage’s ideas about notational sounds are downright wacky. Sheet music could be squiggly lines in different colors, the shapes of which suggest how the performer might proceed.

“That idea of removing your ego as you compose was totally revolutionary, totally against he entire development of Western classical music,” said composer David Ludwig, who teaches at the Curtis Institute of Music. “So many composers — it was really about their egos; imposing their will on music. Cage was a very gentle soul. He saw that as aggressive, and he wanted to take himself out of the process.”

Cage’s effort to compose outside the musical staff may have seemed weird, but it had a profound impact on modern classical music. For example, the first measure of Krzysztof Penderecki’s “Threnody to The Victims of Hiroshima” (used by Stanley Kubrick in “The Shining” and Alfonso Cuarón in “Children of Men”) starts with the composer’s instruction “15 seconds,” wherein all the strings must play their highest note possible. It creates an sonic web of eerie dissonance.

“Using these techniques you get sounds you can never get notating in a traditional way,” said Ludwig. “Cage brings us that.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.