The lost village of Dyottsville

Nowhere does the widespread destruction of Philadelphia’s waterfront history seem crueler than at Dyottsville. Nothing but a grassy field today, this site on the north side of Dyott Street at Richmond Street possesses no less than three claims to historical fame, all intertwined: It was a famous glassworks, whose output still graces the Smithsonian collection in Washington. It was an early utopian community dedicated to educating its workers in the spirit of Christian charity. And it was, for a time, the snake oil capital of America.

The story of Dyottsville is related in The Toadstool Millionaires, a chronicle of medical quackery in America by the late James Harvey Young.

As Young explains, a poor druggists apprentice named Thomas Dyott arrived from England in the 1790s and started out shining shoes. He began making his own boot black, and soon branched into the hot market of “patent medicines” — pills, ointments and potions of dubious medical value.

“Robertson’s Infallible Worm Destroying Lozenges” was a typical Dyott product (The titular Robertson was a grandfather Dyott had invented to lend legitimacy to his potions, and was supposed to be a Scottish doctor). Business took off, and Dyott soon claimed the title of doctor for himself, publicizing fictional tales of his medical experience in London, the West Indies and Philadelphia.

Dyott made Philadelphia the base of a national snake oil operation, Young explains:

Business boomed. Dr. Dyott’s advertisements were displayed prominently in daily papers, of the Eastern cities and occupied columns of space in the rural weeklies of the hinterland. Better to service his far-flung market, Dyott established agencies in New York, Cincinnati, New Orleans, and other cities. His advertisements featured drawings of large Conestoga wagons being loaded from his capacious warehouses with nostrums for the South and West. Besides his own brands, Dyott distributed the old English patent medicines, and the pills and potions of his rivals …

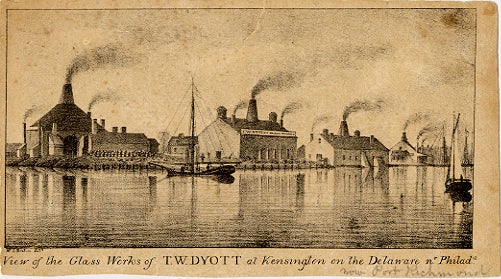

Needing thousands of bottles for his nostrum sales, Dyott acquired a colonial-era glassworks on the Delaware River in 1824 and made a very successful entry into the glassware business (His bottles and flasks can still be bought at auction for $50 to $8,000 per bottle today).

Dyott not only undercut the prices of imported British glassware, but soon was turning out the best grade of bottle glass in America. One product of his factory, preserved in the Smithsonian Institution, was a double portrait flask, honoring those two distinguished adopted sons of Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Dyott.

Catching the spirit of utopian thinkers like Charles Fourier and Robert Owen, Dyott decided to refashion his glassworks as a utopian community, building dormitories, a school, a chapel and enforcing a strict no-alcohol policy.

Nor was his establishment to be disgraced by swearing, fighting, or gambling. Infractions brought deductions from pay. The former druggist’s apprentice decreed that his own hundred apprentices, who lived on the grounds, be taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and singing. They must also bathe and go to Sunday School. They worked a ten-hour day.

It was a veritable Oneida Society on the banks of the Delaware, minus the silverware and the millennial Christianity. As he set about bettering the poor, Dyott himself grew very rich, starting his own bank.

The utopian experiment did not last long. Dyottsville fell apart in the financial panic of 1837, after which Dyott himself was arrested and jailed for attempting to defraud his creditors. Once out of prison, he went back into nostrum sales, and built another fortune before his death in 1861.

Though certainly a blowhard and a liar, Dyott earned one saving grace in Young’s estimation: His ointments, though medically useless, were at least harmless. It’s more than one can say for the wrong-headed treatments carried out by some of the real doctors of the time, who often bled patients to unconsciousness or death.

Sources:

Young, James Harvey. The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in America before Federal Regulation. Princeton University Press: 1961. (online at http://www.quackwatch.org/13Hx/TM/03.html)

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.