What the credit crash means for Philly deals

Oct. 3

By Thomas J. Walsh

For PlanPhilly

Will Philadelphia development be affected by the national fiscal crisis? In a word, yes.

We’re talking real estate, after all, the asset class behind the subprime house of cards that has driven the number of Wall Street investment banks from five to zero in the course of one professional baseball season.

And with the Phillies playing October baseball (in their still-new ballpark, amid the perpetual development site known as the sports complex), the cynic is reminded of how Philadelphia is a town that never gets too high, but never gets too low. We’ve had lots of great teams in all four major sports since 1983, but none that caused a parade. Moses Malone and Dr. J are still standing around waiting to pass that baton.

Through the prism of this cataclysmic credit crash, though, Philadelphia’s middle-of-the-road characteristic is a high positive. Look at the dot-com boom and bust: the Delaware Valley was never mistaken for Silicon Valley East, so the burst bubble left the region nonplussed. The same can be said for the housing downturn. Prices spiked but never hit the stratosphere, relative to some regions of the country, and while homes sit on the market longer these days, area home values have held relatively steady.

The same holds true for Center City Philadelphia development, area experts say. When it comes to the kind of debt-to-equity ratios that have rained ruin on the nation’s capital markets, Philadelphia, it turns out, is in many ways the same play-it-safe town it always was – a significant factor for some of the higher profile projects now being planned.

“It’s a conservative region,” said Walt D’Alessio, the veteran city development guru and commercial real estate executive, from his office at Northmarq Capital in Center City. “We’re very tough on review and consideration, and finally licensing and permitting, although some of it has been pretty spotty at times.”

D’Alessio said local developers are feeling the same pain as anyone around the country who seeks even the most bland type of construction loan or long-term financing. There is simply none to be had right now, and even if the $700 billion federal bailout of troubled banks and other institutions is passed by Congress, the considerable uncertainty of would-be lenders will linger.

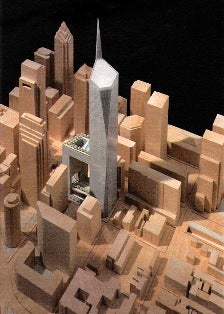

Still, D’Alessio is not overly concerned about Philadelphia’s long-term prospects. Two of the city’s newest office buildings, the Cira Centre and the Comcast Center (the largest in town and completed just this year) total more than 2 million square feet of leasable space, almost all of it already absorbed. Center City’s office vacancy rate hovers at only about 10 percent, a pretty good sign for those who want to build here, he said, such as the investors behind the planned American Commerce Center. It would be a 1,500-foot mixed-use tower planned for the block at 18th and Arch streets that would be among the handful of tallest buildings in the nation if erected.

“Can this city take buildings that size?” D’Alessio said. “Yeah, we just proved that,” he said, referring to the Comcast and Cira buildings. “Will it get financing? Probably not, in this market. … But I’m very bullish on this city’s position.”

And five years from now?

“That’s hard to say, because development is usually a reflection of the market – you’re not going to build speculative space in whatever industry you are in – nobody is making capital available,” said D’Alessio, former chairman of the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp., current chairman of the board for Radnor-based Brandywine Realty Trust and board member for other high-profile Philadelphia companies. “Part of the problem with people looking at real estate is that they want ‘one size fits all.’”

Within a given region, that is, different submarkets demand different investment models. In the best of times, Center City is not South Jersey or King of Prussia, or western Chester County. “We’re a region where a lot of folks don’t sign up for a prelease deal,” D’Alessio said. “Most people say, ‘Build your building, and I’ll decide then.’ We don’t overbuild very often, so there’s not a lot of speculative space out there.”

D’Alessio also said that alternative financing can be found among real estate investment trusts (REITs), publicly traded development and management companies which are relatively flush with capital, low leverage and buffered lines of credit because of their unique structure and mandatory dividends. The region has a surfeit of maturing REITs with solid track records: Liberty Property Trust, Brandywine Realty Trust and PREIT.

American Commerce Center

The consensus is that once the smoke clears, there will be a significant period, perhaps several years, where banks deny credit to any development that is not at least 70 percent preleased, a figure some consider on the low end.

The American Commerce Center, as currently planned, tips the scales at 2.2 million square feet (yes, more than the aforementioned total for the Cira and Comcast centers). It would include a large office portion, residential space, a 30-plus story hotel and conference center, high-end retail spaces and a movie theater. For this long drink of water, 70 percent equals about 1.5 million square feet of preleased space – or more than the equivalent of Suburban Station and the Cira Centre combined.

“The only thing we can continue to do is move forward with the expectation that the capital markets will improve,” said Garrett Miller, president of Hill International Real Estate Partners, a new entity formed when the Marlton, N.J.-based construction management company Hill International bought the stake in the proposal from Miller’s former company, Walnut Street Capital of Philadelphia.

“Obviously there’s a lot of problematic debt,” Miller said. “The investment banking business is gone. The conduit [lending] business is gone.”

That means turning to life insurance companies and pension funds. “It’s come full circle,” Miller said. “Deals will still get done. It’s just a matter of how they’ll get done.”

There’s plenty of money out there, he said. Tapping it within the next few months will be a challenge, no doubt. But “we’re not looking to address the debt yet,” he added. “The development process has 10,000 steps to it, and right now we’re in the first 100. Right now we’re in the zoning process. We won’t be looking to the debt markets until we are 70 percent to 80 percent pre-leased. The days of 30 percent [lease rates for financing] are long gone.”

As far as possible lenders go, “we’ve had conversations, but I don’t think anyone is making decisions on anything this month.”

King condo

Miller thinks the key to preleasing any large development, especially with a large office component, is the health of Center City’s housing and condominium market.

“I think it would be in everyone’s interest to see another residential boom” in Center City, he said. “The condo boom to me has really been a driver for other parts of the market – retail and offices depend on new people, and empty-nesters that come in with a lot of disposable income.” There have been a lot of million-dollar-plus condos sold in the last five years, Miller said, a solid gold sign of health when tallying up the numbers to see what kind of project makes sense to build.

“At least in the case of Philadelphia, I find the condo boom to be extremely beneficial and I hope over the next five years to see a lot more of it,” he added.

Those benefitting from Center City’s condo and apartment boom, in turn, can thank the drafters of key pieces of legislation passed during the Rendell mayoral administration. Tax abatements for abandoned mills and factories that were converted to living spaces brought in tens of thousands of new faces, along with the new money, the new restaurants and the new retail. In time, it brought in new development to complement the in-fill.

“We got rid of all the buggy-whip factories,” D’Alessio said, agreeing with Miller that the tax abatements have “helped immeasurably,” allowing the region in this time of national fiscal crisis to “focus on our strength – our healthcare facilities and education centers. That’s a growth area that even in the recessionary periods – and this is a deep one – continues to go well.”

Other projects

It’s safe to say that no planned development is safe from the ravages of the credit markets, even if financing was shaping up as usual. The events of the last month have thrown almost everything into wait-and-see mode.

The David Grasso mixed-use, 1 million square-foot project at 16th and Vine streets in Franklintown could be up in the air, for instance, despite signed tenants, such as Whole Foods, Best Buy and Intercontinental Hotels. Retail is not in the greatest shape at the moment, analysts say, given the reduction in overall consumer spending. Even Whole Foods and Best Buy aren’t immune – their same-store sales have been volatile – and at the Grasso site they would likely depend much more on residents than tourists or conventioneers.

Not surprisingly, it’s not the greatest time for hotels, either. In addition to the obvious problems with financing, gas prices and decreased business travel have helped drive down room rates in 2008, according to various online indices. The buying-and-selling of hotels, another indicator of the health of the sector, has also slowed to a fraction of the totals for recent years.

At the August meeting of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, Grasso told commissioners that he was awaiting confirmation of financing, which he said was to come partially via the Pennsylvania State Employees’ Retirement System pension fund. He was also angling for subsidies from City Hall, he said.

At the same meeting, developer Bart Blatstein presented his vision of the area at 2nd Street and Girard Avenue (on the site of the former Schmidt’s Brewery), where he plans a grouping of retail and residential low-rise buildings and towers. At the time, Blatstein said tenants were not yet signed, but that his financing was in hand, though he did not provide the commissioners with specifics.

As for Miller’s desire for more condos, developers can only whisper, “From his mouth to God’s ear.” There are about a dozen condominium developments being planned for the Delaware River waterfront north of Penn’s Landing, with more talked about south of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. One of them is the planned Penn Treaty Tower, to be built adjacent to Penn Treaty Park in Fishtown.

It would be home to 168 condos on 32 floors, but even as far back as February, Steve Labov, chief operating officer for local developer NCCB Associates, said demand for condos was “terrible.” Condo towers, unlike office buildings or hotels, depend on people with good jobs and their ability to acquire mortgages.

Mortgage. It’s a word derived from the Old French, meaning “death” coupled with “pledge,” which is sort of implying an almost certain eventual foreclosure, if you think about it.

East Market Street, revisited

Market East is another area of the city with big plans on the drawing board. The Gallery, with its vast blank façade and 1970s-style flourishes above a large commuter rail station, is slated to be redeveloped by Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust, and may well include the limbo-dwelling Foxwoods Casino, now that it has agreed to scram from its intended riverfront location on Columbus Boulevard, just north of the big box retail district.

Joe Coradino, a senior PREIT executive, told PlanPhilly’s Kellie Patrick Gates this week that plans were “too tentative at this point” to discuss, but did confirm new design plans that incorporate the slots palace. In an interview with WHYY-FM on Thursday morning, Coradino suggested that financing major projects will be more of a science than an art for the foreseeable future. “In terms of the existing projects under way, they’ll be completed,” Coradino told a reporter there. For new projects, “you have to be very, very selective” in terms of financing.

At a forum staged by the Central Philadelphia Development Corp. in June, well before the Foxwoods possibility was made public, Coradino said that “better retail and more inviting entrances” to the vast mall, attractive to convention-goers and commuters, was the ticket to a revamped and successful Gallery. Complicating matters even before the market collapse was the fact that while PREIT owns the Gallery’s stores, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority owns the common mall space and the property itself.

PREIT also manages the enormous Girard Estate property across Market Street, a block of retail that tacks forlornly from 11th to 12th streets. Like the infamous “Disney hole” at 8th and Market (now a parking lot), efforts to develop the block have faltered even in the best of times for the credit markets.

Other projects: Extra innings, or cancellation?

The underway expansion of the Pennsylvania Convention Center has prompted talk of more hotels for Center City. Among the locations: 17th & Sansom, 15th & Arch and 12th & Race, with more than 500 new rooms possibly on the market by the end of 2009. That now seems far-fetched. Even more hotels are in preliminary planning stages – at 17th & Arch, 16th & Vine, Broad & Race and 12th & Arch.

Center City hotel occupancy rates have consistently eclipsed the 70 percent mark in recent years. In the current environment, though, anything that doesn’t have a ribbon-cutting scheduled in black ink will be wintering this year in the “doubtful” category. Anything at all questionable under a normal down-cycle for lending will be considered remote possibilities in the wake of this turmoil, national real estate observers say.

Remember: when the Phillies reported to Clearwater, Fla. this year, there were five seemingly stalwart investment banks. With a week or so before the Phils clinched the National League East, there were none. Is it a coincidence that neither the Yankees nor the Mets have made the post-season?

Pickle barrels, Wall Street to Arch Street

But it’s not the investment banks, necessarily, that are troubling developers.

“Investment banks in general did not provide development or construction financing,” said Orest Mandzy, co-owner and managing editor of Commercial Real Estate Direct, a premium Web-based news service in Newtown, Pa. “That’s generally always been the domain of commercial banks. The investment banks would provide permanent financing that they could then securitize. With that market kind of dead now, permanent financing would be provided by insurers via clubs. We’re seeing a lot more of that now. But since insurers have limited balance-sheet capacity, their appetite for financing isn’t that great.” (Full disclosure: I was a reporter for Mandzy at CREDirect from 1999 through 2002.)

“The issue, however, is that we’re in the midst of a major credit crunch. Providers of credit are not willing to provide that credit, almost at any cost,” Mandzy said. “Any lender will want to mitigate as much risk as possible from any project. Remember, just because the project sounds cool doesn’t mean it will pay off economically down the road.”

On the other hand, that doesn’t necessarily mean that a solidly planned building can’t find financing from more traditional lenders.

“Before commercial real estate-backed securities (the financial cousin of the default-laden securitizations backed by homes that brought about much of the current credit crisis), insurance companies were the source of large loans on stabilized trophy properties,” Mandzy noted, meaning sparkling new skyscrapers or reliable high-end hotels, for example. “But most insurers, because of internal risk-management issues, would not want more than, say, a $100 million exposure to any individual market.”

The idea is that if a borrower needed $200 million for an office building in Philadelphia, he would arrange a group, or ‘club,’ of three, four or five insurance companies to provide that debt. Each would take an equal amount, or an amount they could tolerate. “Banks do nearly the same thing through the syndication market,” Mandzy explained. “Bank of America, for instance, could provide $500 million of debt to [a developer] on an unsecured basis, and then sell [on similar terms] pieces of the debt to other banks.”

So it’s not that funds do not exist to finance a complex, ambitious and enormous tower like the American Commerce Center. It’s just that, for the time being, no one wants to provide them. See you in ’09, they’re saying.

Mandzy said that a significant, yet underreported, accounting rule instituted by the Financial Accounting Standards Board in November 2007 (known as FAS 157) requires banks to write down any shaky debt “to market value,” which he said has had a kind of unintended cascading effect.

Language in the latest version of the bailout bill calls for the Securities and Exchange Commission to provide something of a moratorium on enforcement of this policy. Whether or not it is a good idea to loosen federal oversight on accounting for iffy loans, rather than tighten it, remains to be seen. While much of the mess can be legitimately blamed on greed and sloppily underwritten debt, the free market soars and stumbles on appearance and perception, too, and many in the commercial real estate world feel hamstrung by the common mortgage terminology they share with the bubble-deflated housing market.

One thing’s for sure, Mandzy said.

“We’re in a pickle, and it has a debilitating effect on everybody.”

Contact the reporter at tom@thomasjwalsh.info.

On the Web:

• Commercial Real Estate Direct: www.crenews.com

• PREIT: http://www.preit.com/

• American Commerce Center: http://www.acctower.com/

Phillies vs. Milwaukee, National League division series:

• Saturday, 6:30 p.m.

• Sunday (if necessary), time TBA

• Tuesday, (if necessary), time TBA

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.