How rail plays infrastructure role

Aug. 27

By Alan Jaffe

For PlanPhilly

(This is the seventh in a series of stories examining the infrastructure projects proposed in the Civic Vision and Action Plan for the Central Delaware. This article looks at the railways that have had a long, remarkable history on the Delaware River and the possible future of rail on the waterfront.)

Previous stories:

Infrastructure overview

Parks and green space

SEPTA funding

Grappling with I-95

Center City Commuter Connection

The Street Grid

The seven-mile stretch of riverfront from Allegheny Avenue to Oregon Avenue was once the dominion of the rail car. The Pennsylvania Railroad brought freight from the south, rolling down Washington Avenue to the waterfront to unload or pick up cargo at the massive piers. In the north, track after track after track ran along Lehigh Avenue to the waterfront, carrying the coal-black Reading Railroad cars, which hauled millions of tons of anthracite from upstate Pennsylvania for shipment up and down the coast and around the world.

A couple of active lines still run from the Lehigh Viaduct. In South Philadelphia, rail cars still stack up near the freight yards, blocking vehicular traffic. And plans are moving forward for the expanded Southport project beyond the Walt Whitman Bridge.

But on the Central Delaware waterfront, the rule of the rail is over. Colliers awaiting the black fuel no longer line the port. The piers mainly house parties and condos, not cargo. The rail yards are part of an irretrievable industrial past, displaced by technology and geography.

A modernized rail, however, could play a part in the rejuvenation of Center City’s eastern shoreline and help turn it into a 21st-century urban waterfront.

The Northern Yards

From the early 19th to early 20th centuries, the northern Delaware riverfront was known as “the workshop of the world,” a center of industrial manufacturing in Bridesburg, Fishtown, and Kensington.

Cramps Shipyard, now destined for razing and redevelopment, was an economic engine in the region, producing wooden clipper ships and then iron and steel warships for the Civil War through World War II.

The other driving force on the waterfront was the Reading Railroad terminal at Port Richmond, fueled by the steady stream of coal cars coming down from Lackawanna, Luzerne, Schuylkill, Carbon and surrounding counties. Eastern Pennsylvania contained some of the country’s richest seams of anthracite, a dense, high quality coal that was touted as a clean-burning energy source. Western Pennsylvania boasted huge bituminous fields, but that coal burned quickly and dirty.

“There was an advertisement at that time that said, ‘Keep your daughters’ and wives’ dresses clean by using anthracite,’” said Dave Schaaf, an urban designer at the Philadelphia City Planning Commission.

“It was found in Eastern Pennsylvania, just above us. So the Reading Railroad builds lines to those counties. And that’s why Port Richmond develops the way it does, with all those lines to the water, running down along Lehigh Avenue,” Schaaf said. “It was such a desirable coal, it was distributed to the world.”

Colliers, the ships that bore the coal around the intracoastal United States, lined the ports where dozens of railheads met the water. The Reading Railroad’s enormous infrastructure at Port Richmond moved 2.25 million tons of anthracite in the mid-1870s, according to the website “The Necessity for Ruins” (http://ruins.wordpress.com/category/port-richmond-coal-terminal).

The Reading line also transported materiel to the Pennsylvania steel plants, and fruits and vegetables from farms to markets, including tomatoes to the Campbell’s Soup plant in Camden. It was also a major passenger railroad.

But the collapse of the coal business in the 1950s was the turning point for the Northern Central Delaware industrial base. The dozens of tracks to the waterfront grew silent and vacant. Most have been removed from the grasslands that have sprung up on that vast section of the riverfront.

A couple sets of tracks that run down from the Lehigh Viaduct still carry oil and chemicals to the Tioga Marine Terminal and the remaining industries in the area, explained Adam Krom, a transportation planner at the Philadelphia office of the design firm Wallace Roberts & Todd. Conrail, the federally created corporation that resulted from the bankruptcy of the country’s major railroads, owns the tracks and land where rail is still active on the Northern Central Delaware.

Rail and the Port

Besides the end of the coal economy, the rail lines were also limited by the city’s geography. “We were one of the last of the original colonies founded, and there’s a reason for that,” Schaaf explained. “We were the only colony with no Atlantic frontage. All the great ports were taken by the time William Penn gets Pennsylvania.”

Boston Harbor, New York Harbor, Baltimore Harbor, Hampton Roads and Norfolk Harbor – all well known and thriving. “But have you ever heard of Philadelphia Harbor? There isn’t one,” Schaaf said. “This doesn’t negate the fact that we had the largest freshwater port in the world for quite a long time.” But the competing ports, including the neighboring Elizabeth and Newark, have 50-foot drafts in their harbors. The deepest channel on the Philadelphia side of the Delaware is 40 feet to the bottom.

“The governor and the Delaware River Port Authority want to dredge our channel to 45 feet. Our channel is 103 miles long,” Schaaf said. “So our geography does not exactly work for us. We’re not a great natural harbor. The harbors that really do well on the East Coast are the ones right at the Piedmont, where you have the Atlantic coastal plain meeting the Piedmont right at the harbor,” creating deep water at the port.

The Delaware River could comfortably carry 17th and 18th century vessels with relatively shallow hulls. But 20th century shipping eventually made the port at the northern section of the city obsolete.

“Containerization forced ships to be not only enormous, but to actually be stacked really tall,” Schaaf continued. “You can take the containers off at Elizabeth and Newark, make trucks out of them and send them everywhere. Apparently we can’t get a containerized ship below the Walter Whitman Bridge. The Tioga Marine Terminal does have containerization, but it has to be a specific kind of ship.”

Before World War II, “when ships didn’t need a very deep draft, we did fine. Now, our channel is just too shallow.”

The Port to the South

To the south of the Walt Whitman, the expansion of the Southport project is under way. The plan calls for a major, best-in-class containerized facility with the potential of employing 175,000, handling 3.5 million containers a year.

The rail yards in the south remain active, and there are no plans to relocate or in any interfere with those lines in the Action Plan for the Central Delaware, Krom said. “That area will remain very important from a freight-handling standpoint and as a working waterfront.”

The major issue in that area involves the impact of stacked freight cars blocking autos and trucks on Columbus Boulevard, explained Nando Micale, a principal at WRT who leads the firm’s planning and urban design group. The Action Plan and Civic Vision developed by PennPraxis and designed by WRT shifts the tracks slightly south, closer to the industry and piers serviced by the rail lines.

“There’s nothing incompatible with increased port activity, including intermodal rail-truck-ship connections, in the Civic Vision,” Krom said. Some changes to existing track configurations and the street network may be needed, “but there will be no change to function. It will improve function, in fact,” he said.

The Pennsylvania Railroad was the leading line in South Philadelphia and the piers near Center City. The railroad came down to the waterfront from Washington Avenue. The port shifted south over time, and the Philadelphia Belt Line Railroad Company, a consortium of railroads, carried trains all the way to the Navy Yard. The waterfront was “sort of neutral territory for all the railroads, so the shipper could choose which one it wanted to use. The Belt Line allowed for interchanging among the different railroads,” Krom said.

Bob Turner, a consultant for the Belt Line, explained that it was chartered in 1889 “to break up the monopoly of the Pennsylvania Railroad, which controlled the Philadelphia waterfront.” The Belt Line brought in the Baltimore & Ohio and other companies “to make sure the waterfront was open to competitive rail service.”

The Washington Avenue tracks are now gone, and there are few working piers on the Central Delaware. The active railroads to the south are CSX, Norfolk Southern and Canadian Pacific. CSX and Norfolk Southern now own Conrail, although Conrail has served since 1998 as a switching and terminal railroad that operates as an agent for its owners, allowing access for both carriers.

Craig Lewis, vice president of corporate affairs at Norfolk Southern, confirmed that the railroad companies provide no freight service “north of, roughly, South Street.” Norfolk Southern also has been in talks with Foxwoods Casino representatives about doing some reconfiguration so that trains do not travel above the casino’s location, if it is built.

But Lewis said Norfolk Southern’s focus is on business around the Navy Yard, where the company has plans for a new intermodal facility and active rail service in the “relatively near future.”

The company’s longer term program is called the Crescent Corridor, a plan to improve rail infrastructure along Interstate 81 from North Jersey to West Tennessee and divert freight from highways to tracks. “Part of the game plan anticipates new or expanded terminals,” Lewis said, including Philadelphia’s Navy Yard.

As the port is expanded, and if the Action Plan’s proposals for naturalizing areas of the waterfront and creating a street grid to support land development are realized, the southern section of the Central Delaware should complement the rail infrastructure, Krom said. “It will actually neaten up a lot of operations over time.”

A New Role for Waterfront Rail

In the early decades of the 20th century, an elevated rail line ran from Frankford Avenue and down Delaware Avenue, where passengers transferred to the ferries to cross the river. As the port evolved, larger ships docked at larger piers, and ferry service declined with the opening of the Ben Franklin Bridge. The elevated track was torn down.

Passenger rail along the Delaware was briefly revived in the 1990s with a trolley line that serviced the Penn’s Landing area, but it had limited success on a waterfront that never realized its potential.

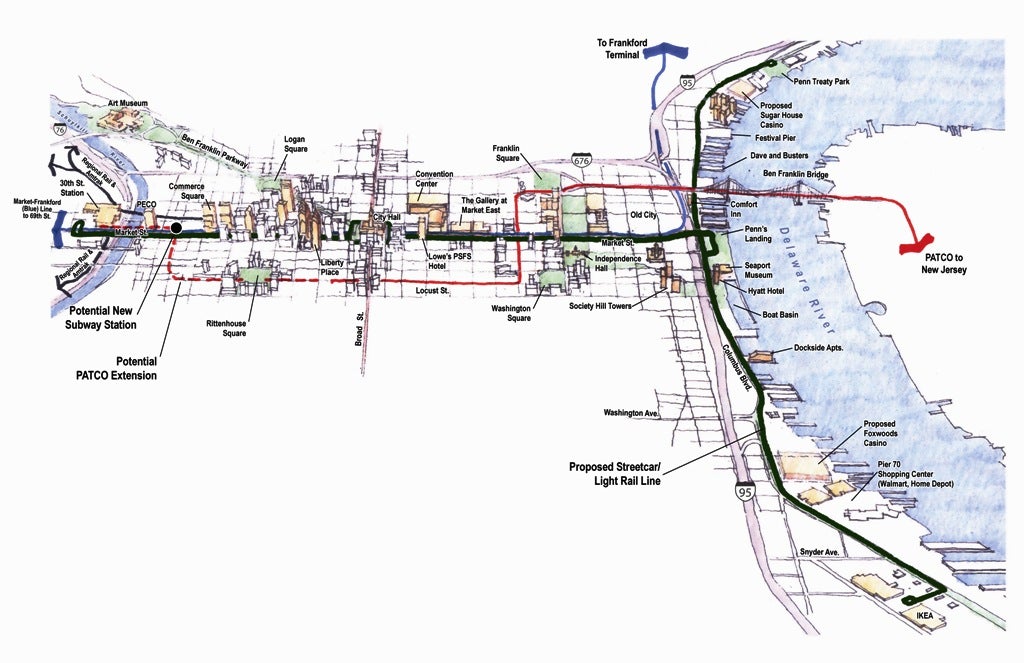

But that same right-of-way used by freight trains in decades past and by the trolley more recently could host a 21st-century track. “The Vision Plan established the idea of potentially having a waterfront light-rail line,” Krom said. The new line could promote riverfront development, provide residents access along the river, and reduce congestion on Columbus Boulevard, he said.

“Light rail generally means fast, higher capacity, modern service, and more efficiency,” Krom explained. “It holds more people, it doesn’t interfere with traffic, and it moves with its own power.”

While the light-rail line in South Jersey uses diesel power because it covers the long route from Camden to Trenton, the Philadelphia line would probably be an electric-powered rail, Krom said.

The right-of-way down the center of the boulevard in the Penn’s Landing area is held by the Belt Line in joint ownership with Conrail, said consultant Bob Turner. “There is not much in the way of industry anymore” in that stretch of riverfront, he added, and “we do not operate at all. … We’re in a sort of holding pattern; our main purpose in life is to make sure there is competitive business on the waterfront.”

If the Belt Line company allows light rail service on the right-of-way, it would reduce start-up costs considerably, Krom said.

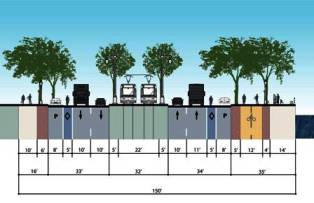

Creation of a rail line down the median of the boulevard, in concert with other pedestrian- and bike-friendly changes along either side of the highway, would reduce auto traffic from six to four lanes. But the Action Plan estimates that a high-frequency streetcar line will be able to transport 2,000 to 3,000 passengers per hour in each direction. “That’s almost twice what a car lane would have carried,” Krom said. “So you’re not losing capacity. You’re just shifting people from automobiles to transit.”

A streetcar line would also reduce parking lots along the waterfront, Krom said. “Tourists will have to park just once. They can access all the destinations on the waterfront by riding light rail. If they come by mass transit, they’d need zero parking spaces.

“Residents wouldn’t need as many cars because car share and light rail would be available to them. So it will help with congestion. And it will cut the high cost of building parking lots,” he said.

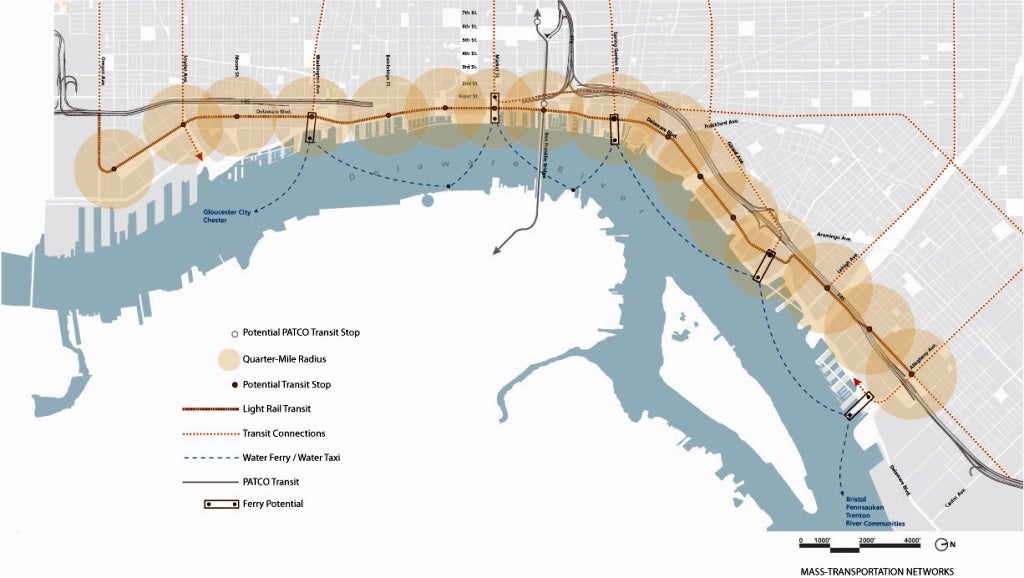

The Delaware River Port Authority, which operates several bridges and the PATCO Hi-Speed Line, is already exploring several alternatives for light rail along Philadelphia’s waterfront.

“An Alternative Analysis study is now under way, which is the first step in the process for applying for federal funding,” said John Matheussen, chief executive officer of DPRA. “We’re looking at potential ridership, cost factors, and environmental impacts.”

The three alternatives under consideration all involve light rail, Matheussen said. “These are street level or underground lines, all complementary to systems already in place. We’ve had good experience with the River Line in New Jersey. This is what light rail is built for.”

Fifty percent of the funding for such a project would come from the federal government, Matheussen said. “The cost of these alternatives is in the high hundreds of millions of dollars up to a billion dollars. We would look for the rest to come from DRPA, the state of Pennsylvania, their trust funds, potential private alternatives, and public-private partnerships.” However, the vast majority large price tag is needed to extend the light rail from the riverfront to Center City; the construction of just the riverfront tracks itself would only cost a very small fraction of this nine-figure amount.

DRPA is half-way through the process of choosing an alternative, he said. The agency’s last round of public input on a waterfront light-rail project will occur this fall. (To view the PATCO alternatives, go to www.patcopaexpansion.com.)

Micale, of WRT, said any transportation system has “funding challenges. It comes down to federal policy. Other cities have funded such projects themselves, or they figured out ways to fund it with minimal federal money. Those tend to be cities in major growth markets; Philadelphia and other East Coast cities tend not to be.”

But in examining successful urban waterfronts, “it’s hard to find places that have not created light-rail systems,” Krom noted. He lists Toronto, Seattle, and San Francisco, which is working on a second light-rail line on its southern waterfront. Many European cities have also incorporated light rail in waterfront renewal. “What most cities are striving for is access to the river,” he said.

From South to North

The PennPraxis proposals recommend a light-rail line that runs the full length of the Central Delaware, from Oregon Avenue to Allegheny Avenue, and possibly beyond in several directions.

“It could extend upward from Oregon Avenue as a major east-west railroad that ends up at the Sports Complex,” Micale said. Other east-west connections could also be made linking the line to Center City along Washington Avenue or Spring Garden Street.

It could also link up with the North Delaware Greenway under construction in Northeast Philadelphia.

The old rail yards to the north have long been the focus of an open space or greenway plan that crosses the city and connects its two great rivers. The path could thread itself around the still active right-of-way running down from the Lehigh Viaduct, “a rails and trails” project as opposed to rails-to-trails, Micale said. “But there’s still a lot to do in-between.”

The light-rail line could also stimulate redevelopment in the southern section of the northern rail yards, which Schaaf noted contains the largest amount of vacant land on the Central Delaware.

Lewis, of Norfolk Southern, noted that some of the PennPraxis plans for the northern rail yards are “probably in conflict with the value of that real property. Unless the community makes some acquisitions” of land, there could be friction between developers and planners. “But I don’t think these things are insurmountable,” he said.

Much of the desirable land on the northern section of the Central Delaware is owned by Conrail, which continues to operate a train five days a week for “a number of customers” in the Tioga Marine Terminal and Port Richmond area, said Conrail spokesman John Enright.

Conrail has sold defunct rail yards in the area around the Walt Whitman Bridge over the past year to the Philadelphia Regional Port Authority, but “we don’t have any specific project in development at this juncture” for the real estate in the north Central Delaware, Enright said.

Conrail is aware of the PennPraxis proposals for mixed uses for the old rail yards, including development and green spaces. “We haven’t met or sat down with PennPraxis about their vision at this point,” he said.

“As a railroad,” he continued, “if we have vacant property and there is an opportunity to develop rail service, that is certainly our preference. That’s not to say we wouldn’t take into consideration other factors, such as the PennPraxis vision or anything else. …We really haven’t had any dialogue with PennPraxis at this point.

“Meanwhile, if an opportunity arrives for developing rail business, we will certainly look at it. We are always open-minded for new rail business,” Enright said.

The northern rail yards have “always been seen as a site for redevelopment,” said Micale, of WRT, “though they’ve never consummated a deal there.” The adjacent Cramps Shipyard grounds are also viewed as a likely site for early action because of the access to the highway and its proximity to Center City.

“The idea is that the boulevard and light-rail initiatives would bring you all the way to this area, so you would set the framework for development in the southern portion of the Conrail site,” he explained.

And a light-rail line could bring new hope to an area where rail was once king.

Contact the writer at alanjaffe@mac.com.

.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.