Green infrastructure’s expense

Nov. 1

By Alan Jaffe

For PlanPhilly

(This is the second in a series of PlanPhilly stories examining the infrastructure projects that would accompany a re-visioning of the Central Delaware waterfront, and how they will meet their biggest challenge: funding. This story looks at the proposals for parks and green space in the Penn Praxis Vision, and who will pay for and maintain them.)

Philadelphians love their parks, and they want more of them. It becomes evident in city agency studies, grassroots movements, approved bond referendums, and well-used green spaces in every neighborhood.

Penn Treaty Park

This is a city, after all, grounded in William Penn’s 17th century vision of a “greene countrie town,” a grid bound by two rivers and built around open squares and parks. Trees, grass and flowing water are in the city’s DNA.

But if Philadelphia is going to continue to grow and attract new residents in the future, it will have to find ways to reclaim and sustain its natural environment.

In its Civic Vision for the Central Delaware, which will be presented to city leaders and the public November 14, Penn Praxis will propose a revised shoreline for the eastern river. A street grid will be extended to the waterfront; Interstate 95 will no longer essentially block access to the river; and vacant industrial sites will be revived as commercial, residential and recreational areas.

The crown jewels of the plan are the parks and open spaces that will be created or enhanced approximately every 2,000 feet along the waterfront, all linked by a greenway that will run the length of the seven-mile stretch. The elaborate necklace of emerald spaces will include wild habitats for birds and fish, pedestrian and biking paths, green streets reconnecting neighborhoods to the water, new or expanded parks, and a 12-acre grand gathering place.

Yet the city’s existing park system is already in a state of flux, with calls for reforming or reconfiguring the under-funded, overburdened Fairmount Park Commission and city Recreation Department. Who, then, will maintain a new chain of open spaces? Who will pay for the greening and cleaning? And how will the land or the access to it be acquired in the first place?

Chicago waterfront

There are many answers to those challenges. Some can be found in other cities around the country that have succeeded in creating or reviving waterfront parks through a variety of financing formulas and forward thinking. Some answers have been found already in similar, sister projects right here in Philadelphia.

Along the Central Delaware, there may be a different path to each patch of green.

The Public Interest

Mami Hara, a principal in the planning and design firm Wallace Roberts & Todd, has been working over the past year and a half with GreenPlan Philadelphia, a cooperative effort of civic groups and 14 municipal agencies to draw up a roadmap for sustainable open space throughout the city. One of the initial steps in the research was visiting neighborhoods to learn what they wanted in terms of city amenities.

“Each area was asked what their priorities are. And there was a real focus in the communities on wanting more open space citywide,” Hara said. “They want more trees and better access to the waterfronts – and to make sure whatever open space there is, is well cared for and safe.”

The people know what’s good for them. According to Nando Micale, a senior associate at WRT who manages planning and urban design, green space is “a land use that’s needed for the public good in a city. You need to have lands set aside to recreate.” Recent studies have shown that when residents have access to parks and recreation, they are happier and healthier, Micale said.

Building green buffers around the city’s waterways has other benefits. “Fairmount Park was created to get people out of the city and into the country. And it was also to protect the water supply. So there are parallels to that and the Delaware,” he said. The city Water Department has been examining ways to create that kind of green “edge condition” around all the region’s rivers and tributaries in order to meet Environmental Protection Agency standards for the Delaware River Watershed. The large and small projects include finding ways to direct storm water into a natural system through parks and green space at the water’s edge.

The shifting profile of the waterfront also raises new possibilities. “In the last few centuries we’ve had an industrial waterfront, and we’ve been in the business of polluting the river,” Micale said. “Now that industry has changed location somewhat, in terms of its transportation modes, the waterfront provides the opportunities to restore the river to a more ecologically balanced state.”

The other advantage of adding parkland along the river is added value. Any public infrastructure increases the value of property, whether it’s nearby roads, power lines, or sewer and water. “Parks also add value. Studies around the country and the world find that property adjacent to parks has more value,” Micale said. In Philadelphia, property values increase with proximity to Rittenhouse Square, or on most any other street that borders a park throughout the city.

And it doesn’t have to be a park. GreenPlan’s studies found that just having trees near a property can provide up to 12 percent enhancement in resale value, Hara said.

Those three big reasons for having parks and greenways – social equity, ecology and economics – are “essentially the definition of sustainability,” Micale said. They improve the health and welfare of the population and the resources themselves, now and for the future.

The Plan

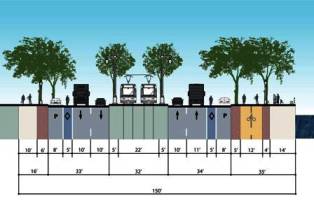

The Civic Plan’s proposals begin back in the river ward neighborhoods, where the main east-west thoroughfares – Oregon Avenue, Snyder Avenue, Morris Street, Washington Avenue, Bainbridge Street, Callowhill Street, Aramingo Avenue, Cumberland Street and Lehigh Avenue – would grow down to the waterfront as “green streets.”

“Green streets means increased accessibility in terms of bike paths and landscape amenities such as tree cover and plantings,” Micale explained. “They also have more intensive storm water management treatment in terms of rain gardens incorporated into the landscapes. Storm water is captured that way rather than directly into the storm sewer system.

“From a physical point of view, it’s about trees, and also the width of the streets. They are big corridors that provide for connections and allow for more amenities to be put in.”

According to the plan, Snyder Avenue would spread into a wide boulevard and end in a storm water park at the location of a historic stream in South Philadelphia. “By re-creating this green space, you’re able to put the water back to where the water wants to go, even though that stream has been filled in. From a topographic point of view, there’s a re-creation of that hydrology for the area,” Micale said.

From the storm water park heading south to the city-owned Pier 70 area, on the edge of the current Wal-Mart site, the plan calls for an “ecological, naturalized edge” along the river. It would be allowed to revert to a “sort of wildness,” becoming a habitat for birds and fish, but would also provide recreational resources for people, like the Wissahickon banks, Micale said.

A 300-foot-wide swath of green is proposed, bordered by the water and a river road with some development along it. The goal is the construction of tidal marshlands on that portion of the river. “The Delaware is a tidal river, and the flora and fauna that would inhabit that area need to have a constructed edge condition as opposed to a natural waterfront,” Micale said. One technique that could be used is the deconstruction of one of the pier structures, allowing it to become a protective barrier for the creation of wetlands and wild habitats. The Delaware once contained protective islands, like barrier islands that protect the intercoastal edge. “That’s the technique we’re looking at to create an ecological edge.”

To maintain a balance between ecological and recreational concerns, the plan calls for a linear, 100-foot greenway to give people access to the water. On the pier side, there can be housing. “So some places are going to be natural, and some places are going to be inhabited by humans,” Micale said. “But they’re all connected by the green edge.”

Old Swedes

The Civic Plan has plotted out a park or green space about every 2,000 feet along the Delaware. The next big park heading south is at the end of Washington Avenue, which is currently a combination of properties, including the Old Swede’s Church site, private land, and the Coast Guard headquarters. The plan reorients Washington Avenue to the south to open up more space, and would pick up even more land when the Coast Guard redevelops its site into a more contained, secure property. The result would be a mix of public and private land forming a park at the foot of the avenue.

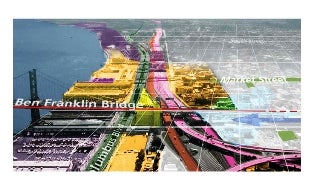

If the riverfront greenway is a necklace, the next link is the diamond pendant.

Running from Lombard to Market Streets, covering what is the current Penn’s Landing property and connecting back through Dock Street into the historic district, is the plan’s big waterfront park.

“The strategy is to balance development and open space by reconfiguring Penn’s Landing,” Micale said. “From a civic point of view, that’s the place where we want the great space.”

How great? The new Penn’s Landing park would be approximately 12 acres, or about twice as large as Rittenhouse Square. The basin on the river would become an active marina, which pedestrians could circle by way of an esplanade and draw bridges. At the foot of Dock Street would be “a public dock where people can come down and touch the water.”

The next major green space to the south involves reclaiming land that is now part of the highway system. The plan envisions depressing Interstate 95 in the central area, and utilizing some of the land above and around it as a series of parks connecting the city to the river. One park runs along Willow Street, following the path of another historic stream. At the site of the old West Shipyard, part of the original British settlement, would be an archaeological park that would unearth historic roots.

At the end of Spring Garden Street, a park promenade along Festival Pier is planned, connecting the greenway around developments in that vicinity.

Penn Treaty Park already stands at the next point, at the end of Columbus Avenue. As the Girard Avenue Interchange is redeveloped and a ramp is removed along Richmond Avenue, the plan is to redirect Columbus Boulevard in front of the Peco station, thereby enhancing Penn Treaty Park. The interchange redo will make land available for parking lots and recreational uses, such as a skate park and trails that can run along and under the highway.

The interchange work will allow development of a park that manages storm water for the highway, including water infiltration and trenching systems under plantings, and living, green screen walls that clean the air and muffle the noise. It also poses the opportunity to reconstruct another former stream, Gunners Run, that came out near Aramingo Avenue. The site had been an 18th century utopian settlement called Dyottsville, an industrial village with a glass works. It is now vacant industrial land between two bulkhead piers. But “it has all the conditions for a bird habitat,” Micale said.

The greenway would become more of an urban path through some of the northern areas, but would return to the edge of the river around the SugarHouse casino site, which has a right-of-way along the waterfront.

Ore Pier renewal

At the end of Cumberland Street, where the Ore Pier stands, another small park is planned, part of a linear green space that reaches down to an expanded Pulaski Park.

Around Pulaski are various opportunities to explore the area’s industrial heritage, perhaps finding ways to re-purpose some of the old tanks and dry docks as green space. The park itself may be expanded by absorbing what is currently a city impound lot.

Habitat restorations and ecological parks are also planned on part of the Conrail site at the Lehigh viaduct.

“An ecological park doesn’t mean people can’t go in it,” Micale said. “The aim is that people will go in it, but in a controlled way,” over boardwalks that cause the least ecological impact.

Neighboring Lessons

The Penn Praxis Civic Vision ends around Allegheny Avenue, and for the most part exists only on paper and in the imaginations of the planners. But just a bit farther north, a similar plan with similar goals is taking shape.

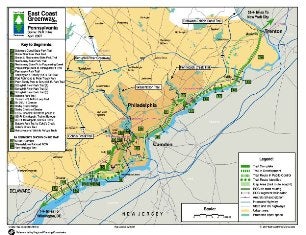

The North Delaware River Greenway began 10 years ago, when then-Congressman Bob Borski saw that the abandonment of industrial sites and the erection of I-95 had cut off his Northeast Philadelphia constituents from the Delaware. He envisioned redeveloping the waterfront for residential, commercial, industrial and recreational uses. A plan was laid out in 2001 by the Pennsylvania Environmental Council, a nonprofit advocacy group, which looked at the riverfront from Penn Treaty Park to Grant Avenue.

“It was really a great first step, but it was not specific enough on how to implement it,” said Sarah Thorp, executive director of the Delaware River City Corporation, the nonprofit that is now overseeing a revised plan for an 11-mile greenway that will run from the Betsy Ross Bridge to Linden Avenue. The original plan “was great for looking at design and a vision, but then it needs to be practical. It needs to be based in economics.”

A cost-benefit analysis was conducted, examining three types of investment in the northern waterfront: one that called for a small public investment using what already existed, an intermediate investment, and a large investment that required the acquisition of a lot of land and environmental remediation. “What they found was the regional economic impact was the highest with the large scenario,” Thorp said.

The recommendations for the plan included the creation of the DRCC in 2004, supported by the business privilege tax program. The organization’s corporate sponsor, Chickie’s and Pete’s Restaurant, covers DRCC’s $100,000 annual budget instead of paying a city business tax. Thorp, a former Navy pilot, historic preservation student and Kensington neighborhood activist, was hired to lead the group last year.

The first order of business was creation of strategic and operating plans, which determined that DRCC was going to be “a maintenance and operating organization for the trail and some of the park spaces along it,” Thorp said.

The Fairmount Park Commission will own almost all the land involved, and the city will own “all of the stuff that we’re developing. That’s kind of for liability purposes,” she said. “So the model is that the city will own it, and we will operate and maintain it, in coordination with FPC.”

It’s the same model used by the Schuylkill River Development Corporation, which is leading the creation of the Schuylkill Banks trail and other improvements along that river. “There are some things Fairmount Park does, some things the nonprofit does, and some things that are contracted out to a third party,” Thorp explained.

“It’s a complicated model of maintenance, but it’s necessary in Philadelphia. We don’t have the budget in our park system to do the maintenance for this sort of infrastructure, so the funds have to be raised some other way.”

Portions of the DRCC’s $1.5 million operating and maintenance budget will come from grants, the city Commerce Department, and the business privilege tax program. But that won’t account for all of it, “so we’re thinking about the business improvement district, or tax increment financing for different types of long-term financing for the trail,” Thorp said, referring to a method used in Atlanta and other cities for large greenway projects that needed big amounts up front for infrastructure.

“We’re estimating a total of $150 million capital budget, and we only have raised about $30 million so far. We have a lot of capital fundraising that still needs to be done,” she said. “A lot of the money is federal transportation money right now.”

The Greenway project is currently in different stages of acquisition, which will be followed by design, remediation and construction phases. “Projects like this are built as you can do them. You’d love to just start at one end of the trail and just go straight up to the north end. But it has to be done the way that you’ve got it,” Thorp explained.

“We’re starting with areas where the city already owns the land. In those areas, where the acquisition is already done, those are the places that we’re moving the fastest.”

In the middle of the Greenway is a city-owned railroad right-of-way, including a section deeded to the city by Conrail for $1. Another portion of city land between Rhawn Street and Linden Avenue has five different prisons and a major water treatment plant. “So it’s pretty important stuff going on in this little area. But there’s certainly space along the riverfront to put in a trail and add on some new park area.”

An extension of the Greenway into Pennypack Park is fully funded, fully designed, and awaiting paperwork before construction begins. That part of the trail is being funded by a grant from the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. The same grant will pick up some of the cost of construction at Lardner’s Point Park, at the base of the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge. Lardner’s Point, which will be the 64th park in the Fairmount Park system, will include new wildlife habitat in the marsh and shrub areas of the former industrial site. Some of the money for that is expected from a mitigation fund for an oil spill near Tinicum a couple of years ago.

Private developers along the Northern Delaware have been “very much on board” with the Greenway project, Thorp said. The new waterfront redevelopment zoning classification put in place a few years ago requires developers to include a 50-foot setback along the river. But they don’t have to choose that designation.

“One of the things we need is better zoning; we need something that’s mandatory so that a developer can’t buy a parcel and not do riverfront zoning. The political will and the pressure right now probably wouldn’t allow that to happen. But the fact is, you need policies that reflect the will of the people.”

The four large developers in Thorp’s area have all elected to include the setback. “All of them are doing a riverfront trail, and they’re paying for the trail to go through their section,” she said. And it’s in their self-interest.

The sites are isolated from neighborhoods and need new roads and water infrastructure. In return for the city’s help in building some of the infrastructure, the developers will create the trails and maintain them for 10 to 20 years, or until a homeowners association takes over maintenance.

Aside from zoning issues, Thorp said her biggest problem has been wading through the federal funding quagmire. “Federal money doesn’t come to a nonprofit; it comes to the city,” which has meant following the paper trail through PennDot, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, the state Transportation Improvement Plan, and the city Streets Department.

“The longer you wait, the more things cost, and the less you get done,” Thorp said.

The small size of her staff – one full-time and one part-time person – doesn’t provide much political clout or fund-raising leverage. So she meets with colleagues in the Schuylkill group, with civic leaders in East Falls and Manayunk, and with planners for the Central Delaware.

“We need a riverfront consortium with all these different groups,” Thorp said. “We need to decide what we all have in common and push for those policies, so that we’re all moving in that direction.”

City Limits

When Mark Focht, the executive director of the Fairmount Park Commission, talks about successful new park projects in the city, he points to the North Delaware River Greenway and the Schuylkill River Development Corporation. And, he said, the city should “absolutely” support the planning for the Central Delaware.

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with the concept of thinking big, while at the same time struggling with what’s on our plate today,” he said.

What FPC is currently struggling with is responsibility for 63 city parks on a $13.1 million budget this year. “Our budget has basically flat-lined for the last decade or more,” Focht said. “A colleague of mine recently commented that, ‘We used to do a lot with a little; now we do everything with nothing.’ That sums up the pressures we feel are on us on a daily basis.”

So can it take on maintenance of another string of parks along the Delaware? “Not given our current budget,” Focht said.

Major initiatives like the Greenway, Schuylkill Banks, and the Central Delaware vision “simply can’t be implemented with the current level of funding and staffing we have. If the city wants to build these — great. If they want to maintain them, resources need to be provided.”

The park commission is working on partnerships with the Greenway and Schuylkill groups to find capital to keep the projects moving. “For example, we have access to federal grants and programs that are set up to specifically to support government entities. They also involve a lot of paperwork and minutia that is best left to government, because that’s how we function – we speak that language,” he said.

On the flipside, “you have foundations, corporations and citizens who are weary of giving to government and want to give to a nonprofit for tax benefits. And they trust that there’s more accountability with a nonprofit that those dollars will be used wisely.”

But those sources are seldom interested in underwriting management and maintenance costs, and the constraints on the city budget leave few dollars for park preservation.

“There has to be some innovative thinking about how you access resources from lands that benefit from these public improvements,” Focht said. Possibilities are the special services district model, or diverting a percentage of the real estate transfer tax on improved value of homes near the parks, he said. “There are a lot of models nationally that can create funding streams for maintenance and programming.”

It is relatively easy to find money “to build things,” Focht explained. “If people are jazzed up by a broad vision and it has a broad base of support, you find money to do it … It’s much tougher to find money to maintain it. Maintenance is not sexy.”

But as it has done with the Greenway and the SRDC, the park commission could forge a partnership with whatever management entity is formed on the Central Delaware. And Focht said that creating one organization that can “establish standards that are imposed the entire length” of the waterfront is beneficial to everyone involved.

“If this is truly public open space, the city should own the land. It’s then placed under the jurisdiction of Fairmount Parks. So it’s within our inventory, we’re responsible for it, and I think that’s appropriate,” he said.

FPC would then enter into a management, maintenance, and programming agreement with the nonprofit entity “that says we do this, they do that. We don’t fully abdicate our responsibility.”

Regarding upkeep, FPC does “ordinary maintenance,” like mowing and snow removal, while SRDC is responsible for “extraordinary maintenance,” like seasonal plantings.

And the park commission usually offers to use its arborists and labor contracts to manage the properties. “In our partnership agreements, we’ve said we’ll manage it all. We just can’t afford to pay for it.”

The city Recreation Department has the same problems. It staffs 150 rec centers and playgrounds and directs most of its resources there. It is also responsible for the maintenance of 79 neighborhood parks, “which are basically passive, open green spaces,” said parks coordinator Barbara McCabe. But she said in Philadelphia, all the green spaces are very active, not passive.

Covering those 79 parks, which range from a quarter-acre to 45 acres, are 34 staffers. “So we’re a bit strapped right now. The numbers don’t jibe. We have all of these facilities, and we just don’t have enough people,” McCabe said.

The department does contract out for lawn mowing and trimming, or for repair of benches or safety hazards. It has also developed partnerships with Philadelphia Green, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society’s community outreach program, and with neighborhood friends groups.

The creation of new parks and green space along the Delaware waterfront should include “any kind of public-private partnership that can be forged,” McCabe said.

“The truth of the matter is, the budgets are not going to get bigger. The city has a lot of demands – police, fire, streets, all that. They’re very essential needs. Unfortunately, when it comes to budget, it’s almost like recreation and parks are a luxury. Really, they’re not. But when it comes to budget time, and you have to cut things, it seems that’s the way it goes. To think that the city is always going to increase budgets – I don’t know how realistic that is. So we have to find another way to do it, before they’re built.”

City Council has been debating reforms of the park commission, and a possible merging with the Recreation Department, for several years. A ballot initiative to reform FPC has been led by Councilman Darrell L. Clarke. His bill, supported by the Philadelphia Parks Alliance, would shift the power of appointing park commissioners from city judges to the mayor and Council. In September, the bill failed to get the Council votes it needed to get on the November ballot. It could be revived for the primary ballot in the spring.

A State of Flux

Questions of acquisition and maintenance are just beginning to be addressed in conversations about the Civic Vision for the Central Delaware. The opportunities for federal, state and municipal involvement and options for regional partnerships will be part of the discussions in coming months, if not years.

“There are lots of different approaches you can use in negotiating either transfer of land or easements into the public domain,” said WRT’s Mami Hara.

Some cities consider voluntary contributions by landowners as a best practice, she said. “They work with landowners to demonstrate the public good, and the benefits for any land that they retain.”

Others cities find the best approach is regulatory controls that require dedication of easements or enhancements triggered by development permits. “The issue is when the trails or parks don’t develop until somebody initiates some kind of change on the property,” Hara said.

An example of that approach is the Hudson River Trail in New York. WRT performed the planning for the trail through Hudson River Valley 20 years ago, and it is still being implemented incrementally, “although many sections are very successful,” Micale said.

St. Louis has used a percentage of a sales tax to develop an ambitious greenway system. “They use one-tenth of one percent of the sales tax on a limited number of goods, and that’s been able to finance a huge amount,” Hara said.

The water district in Omaha has used an increment of a sales tax to create linear parks along its streams for ecological reasons, Micale noted.

And some cities look at partnerships with land conservancies. “If there’s a high resource value, culturally or environmentally, and there’s an important role for the land regionally or on a large scale, the conservancies can play a big role in helping to develop financing strategies and use their leverage for partnerships,” Hara said.

“A lot of times, it’s a mixture” of financing methods, she said, “and it’s always tailored to the conditions on the ground. You can’t pick a strategy until you know who the players are, and what the concerns of the constituents are. It’s not going to work unless it’s tailored to everybody’s needs and agendas.

“Once people start to see success and understand the role that a green armature can play for a development, and quality of life, then it becomes easier,” Hara said.

As to park maintenance, creative partnerships will probably come into play again.

“The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society maintains a lot of open space in Philadelphia that the Fairmount Park Commission and the city cannot,” Micale said.

“I think in the end, it’s going to be a combination of things. Other cities have a variety of organizations. In Boston, the municipal park called Post Office Square is actually managed by the consortium of landowners that developed the parking garage underneath the square.”

In Philadelphia, there will be different models depending on the players and the location, and the future roles of FPC and the Recreation Department, Micale said.

“It’s a big open question. There are a lot of ways to do it, and we’re in a state of flux right now. As a city, we’re looking to reform some of the older government structures that are in place. Parks management is certainly one of them.”

Alan Jaffe is a former Philadelphia Inquirer editor. Contact him at alanjaffe@mac.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.