July 16

By Matt Blanchard

As she watches developers planning 23 new condominium towers on the Delaware riverfront, Janice Woodcock can’t help but ask herself a question: “Where are all the cranes?”

And because she is head of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, Woodcock also knows the answer: “The cranes are waiting for a market.”

That booming market was here in 2006, but now it’s gone. A slump in the national and local real estate markets has derailed several new projects on the Philadelphia riverfront and seems to have delayed everything else.

According to Dr. Kevin Gillen, a real estate economist at the Wharton School, the market turned in the second quarter of 2006. Back then, the average house in the Philadelphia area spent only 35 days on the market before being sold. Today that number has climbed to 65 days for all housing and 80 days for condominiums. As a result, the inventory of unoccupied condos has risen, giving buyers a greater range of choices and exerting a downward pressure on prices.

The Slump Dynamic

All this spells trouble for developers of new condo projects, on the riverfront or anywhere else. With so much inventory on the market, buyers are less willing to put down a deposit for a condo that doesn’t exist yet, what realtors call presales.

Without presales, condo developers can’t get funding from banks and other lenders, who typically want to see between 20 and 50 percent of units pre-sold before construction begins. Unless they are bankrolling the projects themselves, developers who lose financing are developers who have lost their projects.

An early victim of the slump dynamic was Marina View Tower, a 30-story project proposed for a site just north of the Ben Franklin Bridge. The development team had pre-sold an impressive 60 of its 197 units, but the deal fell apart and the project was shelved in August 2006.

Other projects could face the same fate.

George Cahill, a specialist in waterfront real estate who leads a Coldwell Banker office in Old City, speculated that new condo construction would have to secure deposits at prices approaching $600 per square foot.

“Right now the market’s not pulling those kinds of numbers,” Cahill said. So far as he knew, only one project, Trump Tower, was still taking deposits from potential buyers, and they still haven’t broken ground.

Saved by the Slump?

To some in the architecture and planning community, however, this slump is a very good thing.

That’s because many of these projects are designed as isolated towers perched atop multi-story parking garages. That stirs up fears that we’ll end up with Downtown Houston on the Delaware, an incoherent realm of windswept streets and blank walls, geared more to automotive efficiency than to human enjoyment.

Trump Tower, a $300 million condominium project on the river at Fairmount Ave., appears to exemplify the type. It’s a 45-story monolith seated on what renderings suggest is a 3-story, 370-car parking garage. Though luxurious on the inside, it offers little to the street and relates not at all to its surroundings.

It’s precisely the sort of approach that Penn Praxis director Harris Steinberg is working to avoid. Tasked by Mayor Street with creating a comprehensive waterfront plan, Steinberg and his team are in a race against the real estate market. Can Steinberg get his plan in place before the market picks up?

If he loses, Steinberg says we’ll get Downtown Houston on the Delaware. If he wins, Steinberg says we’ll get something more like Rittenhouse Square.

“The goal is to create the kind of livable neighborhoods that will draw people down to the river in an elegant and humane way, much like you’d go down to Rittenhouse Square,” Steinberg said. “The designs that are currently on the boards don’t do that. From what I can see … it would be a forest of individual buildings instead of a collective cityscape.”

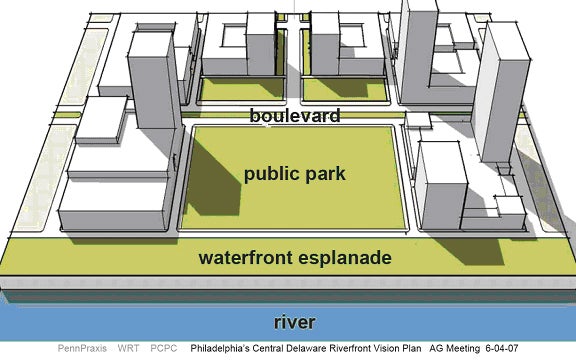

After 9 months of work, Penn Praxis has prepared a set of “design guidelines” that call for a more Philadelphian cityscape. Instead of individual mega-projects, the guidelines call for a street grid of small blocks, buildings that come right up to the sidewalk, and first-floor retail that will foster a lively street life.

In order to give these guidelines the force of law, Steinberg is talking to the Planning Commission and City Councilman Frank DiCicco about creating a zoning overlay district for the waterfront. Such a measure would have to pass City Council. To see a PDF abstract diagram of what the design guidelines would create,

click here.

How long a slump?

Steinberg will have to work fast. Observers expect the Philadelphia real estate market to pick up soon, with the waterfront perhaps leading the way.

Part of the reason is that Philadelphia’s slump has so far been mild compared to cities like Miami, where fevered speculation drove massive over-supply of the housing market.

Also, market fundamentals for the city’s core areas are said to be strong. According to the Center City District, the Center City market has been absorbing an average of 1,397 housing units each year from 2000 to 2006. If that impressive rate continues, several thousand new units on the riverfront doesn’t sound far fetched.

And the arrival of casinos might provide a shot in the arm. SugarHouse and Foxwoods represent together about $1 billion in development dollars.

Observers like Steve Mullin of the Econsult Corporation expect to see that investment spur more activity on nearby sites: “I think construction will pick up as soon as the shovels go in the ground for the two casinos,” said Mullin, whose firm was hired by Foxwoods to conduct an economic impact study in 2006.

Yet it is worth asking: Would a big-box casino attract condo-dwellers to live next door? Or would it repel them?

Broker George Cahill, too, is positively bullish: “The waterfront is going to be exploding in the next five years. Even if half of the [proposed projects] pan out, it’ll be a whole new community,” he said.

The question is: What will that whole new community look like? Like a high-rise boom town? Or like a finely-planned new neighborhood of Philadelphia?

Architect Alan Greenberger, chairman of the Design Advocacy Group, is among those who hope that the real estate slump will give an edge to planners over builders in this race for the future of the riverfront.

“Some of these projects out there now will probably do significant damage to making the waterfront a public place,” Greenberger said. “It will be a collection of random ideas, strung out along a road devoted to the car.”

“The slump probably helps,” he added, “because it buys time.”

City planning head Janice Woodcock agrees. Successful waterfronts in New York, Baltimore and Vancouver have all relied on cooperation between developers and city government through a plan endorsed by the public.

To develop in a haphazard, uncoordinated fashion is to sell our waterfront short.

“I can absolutely say, if you end up with parcels developed piecemeal, there will be no question you could have done better with a plan that everybody loved,” Woodcock said. Should current trends continue, she added, “the overall appeal and overall value of the waterfront will be decreased.”