Onboard the S.S. United States

May 31

By Steven B. Ujifusa

For PlanPhilly

On April 24 and 25, a production crew of about a dozen people swarmed over the decks and deserted lounges of the S.S. United States, recreating the life and vitality she possessed back in her glory days as a transatlantic liner. The crew was filming a PBS documentary about the ship, directed by Robert Radler and produced by Mark Perry, with the support of the S.S. United States Conservancy. The documentary is scheduled for release in early 2008. At the invitation of S.S. United States Conservancy’s President Susan Gibbs, I was asked to be a volunteer production assistant. These two days with the production crew was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity not just to come onboard a great ship, but to participate in an effort that will raise awareness about one of America’s greatest engineering triumphs.

A great name continues to grace the bow. The ship has not been painted since 1969. Photograph by author.

The rusting flagship of the American merchant marine and the fastest passenger ship ever built sits under heavy guard at a South Philadelphia pier, behind a maze of barbed wire fences and security cameras. Beyond the fence, the area buzzes with the life of a busy port, with forklifts, trucks and pick-ups darting around the pavement off-loading cargo from ships docked at piers adjacent to the S.S. United States. Due to modern day concerns such as heightened national security and other regulations, the inner workings of Philadelphia’s port have now been cordoned off from public view. Aside from stevedores and other port authority workers, few visitors are allowed to get close to the ship. Almost no one, aside from the caretaker and authorized officials from the ship’s current owners, Norwegian Cruise Lines, are allowed on board.

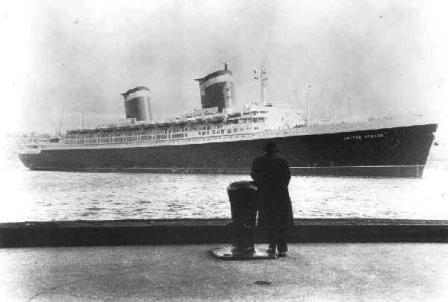

The S.S. United States departing New York City, c. 1960, showing off her fine lines and vibrant colors. http://www.ssunitedstates.org/gif/shipphotos/ship_skyline_lg.jpg

Forty years ago, a liner this size would have generated a frenzy of dockside activity when docked in New York, in preparation for her voyage to Europe. Glittering Cadillacs and Lincolns—belonging to her wealthiest first class passengers–would be hoisted from the pier and lowered into her forward cargo holds. Enough fine meats and produce to feed up to 2,000 passengers for the four day trip from New York to Southampton, as well as hundreds of cases of the best wines and champagnes, would be carried by conveyor belt from the pier through the gangway doors. Cargo destined for New York’s finest department stores would be offloaded onto trucks, as well as hundreds of bags of mail.

View of the ship’s knife-like prow, designed to pierce through the North Atlantic at speeds up to 43 knots, or almost 50 miles an hour. The anchor chain rust scar is visible on the port side. Photograph by author.

As I approached the pier, the great ship’s immense size and elegant lines became fully apparent. The wind coming off the Delaware River caused the liner to drift back and forth several feet from the pier, causing groaning from the ship and shrieking from the lines tying her down. The vessel is 990 feet long (the length of three football fields), 100 feet wide, and looms 12 stories above the water from waterline to funnel tops. However, she is so wonderfully proportioned that she still possesses the grace of a yacht. Her prow is like a stainless steel knife, meant to cut through the North Atlantic with impunity at 45 miles an hour. Her “spoon” stern is rounded and graceful. Yet her fine lines are not simply aesthetic; when completed in 1952, the ship’s hull design and engines were classified military secrets due to her status as a stand-by troopship. Her low superstructure and finned smokestacks were designed to minimize wind resistance as she sliced through fierce Atlantic gales.

Despite her visual majesty, the real extent of the damage caused by forty years of neglect became obvious as I got closer. Stripped of almost all interior appointments and carrying no fuel or freight, she rides very high in the water, and is weighed down at the stern by her engines. The ship’s four propellers perched on the fantail are a clear reminder that she can no longer move under her own power. While being hoisted up on deck, one of the propellers caught a section of stern railing and badly mangled it.

The windows to the cabin class lounge and smoking room promenade, located near the stern of the ship. Four decades of neglect are sadly apparent in this picture. Photograph by author.

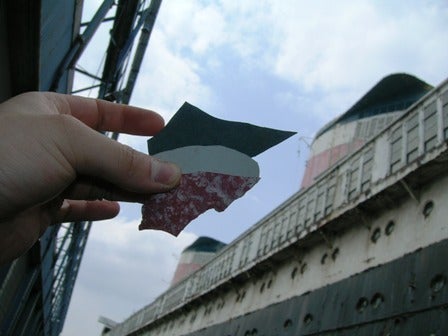

The ship’s exterior paint is in atrocious condition, a result of exposure to decades of harsh sunlight and two long tows across the Atlantic in the mid-90s. The last time the ship was painted was 1969, in preparation for an around-the-world cruise that never happened. The steel plated hull, built to withstand the great storms of the North Atlantic as well as multiple torpedo hits, is scarred with gigantic rust patches. An especially nasty rust scar caused by a dragging anchor chain disfigures her prow. Sheets of black paint from the hull and white paint from the superstructure dangle precariously from the side of the ship. The red boot-topping paint that protected the ship’s hull from corrosion below the waterline has faded to a ghoulish grey. Paint chips, some nearly a foot in length, lie scattered like autumn leaves along the pier’s loading dock. Some chips from the hull are quite thick, with the layers peeling apart like leaves of a book, indicating how many times the ship was painted during her seventeen years of service.

Most poignant are the red, white, and blue chips that have peeled off the two smokestacks and now lie like so much confetti on the pavement. Looking up at the stacks from the dock, I guessed that about half of the paint from the smokestacks has flaked off, leaving only bare aluminum. When I shredded a few of these sun-bleached flakes, the vibrant colors that the great ship once wore came alive.

Impromptu study in red, white and blue made from paint chips that have fallen from the ship’s funnels. Photograph by author.

Despite the poor cosmetic condition of the ship’s exterior, studies have shown that the hull that is still strong and in excellent condition, and that a thorough sandblasting will eradicate the corrosion damage. In addition, she has passed Norwegian Cruise Lines’ preliminary engineering evaluation for the rigorous 2010 SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea) regulations, which will place stringent demands for newly-constructed ships and older liners in terms of the stability and the ability to stay afloat in the event of a collision [i]. This performance is a testament to the skill of her designers over five decades ago.

View aft from just under the port bridge wing. Photograph by author.

A stern view of the ship. The railing was damaged when the four propellers were removed and placed on the fantail. Photograph by author.

It was beside the great liner that I joined director Bob Radler and producer Mark Perry. I had met Bob the previous evening at the Comfort Inn, where he had showed me how to download the digital camera footage onto a computer hard drive. Bob’s passion for the S.S. United States started as a film student in 1975, when he documented the ship during her lay-up in Norfolk, VA. At that time, she had been there for just six years and still looked ready for departure, with the beds still made and newspapers folded on the lounge tables. Now, after a successful thirty years in the movie business, Radler was returning to a subject that had fascinated him as a student.

Producer Perry has also had a successful career in film and TV, and passionate about the S.S. United States since his childhood. He currently possesses one of the largest and finest collections of ocean liner memorabilia in the world, and has been editing and posting rare vintage liner movies from the 1920s to the 1960s on Youtube.com.

Susan Gibbs, President of the S.S. United States Conservancy and grand-daughter of the ship’s designer, arrived later that day with her teenage daughter Antonia. An independent foreign policy consultant, Susan has not only worked tirelessly to save the ship itself, but to preserve the vessel’s human story by assembling a treasure trove of oral histories, movies and photographs from passengers and crew. Susan was also eager to give her daughter a close-up look at her ancestor’s greatest engineering achievement.

Part of the production crew takes a break on the pier during the shooting. Photograph by author.

The shooting of the documentary had started an hour before my arrival, and a few camera men were already at work, shooting exterior shots of the vessel from all angles. A number of cars were pulled up beside the ship, doors thrown open and production crew conferring within. The ship was not going to be accessible until mid-afternoon. Among those being interviewed in front of the ship included officials from Norwegian Cruise Lines, Susan Gibbs, and Shirley Barol, who traveled with her late husband on the maiden voyage in 1952. During interludes, I walked around the ship taking my own pictures.

Finally, at mid afternoon and to the general excitement of the production crew, we were granted permission by the owners to board the ship and start our filming. We entered the ship through a former crew gangway amidships on the port side, the side facing the pier. Access is by a narrow aluminum gangway that is slid by brute strength through the gangway door and lashed down to a bollard. Crossing the gangway to board the ship a bit of courage, especially as the ship drifts from side to side and the drop is about 20 feet. The open gangway door reveals little but a murky black cave illuminated by a few portholes on the opposite side of the ship. The real challenge is finding one’s way through the ship once aboard. As we entered the foyer, the interior of the ship was dark and dank. The ship smelled of fuel oil and mildew. White paint was peeling off the partitions and piping.

The crew gangway and make shift gangplank. The metal security doors are a modern addition. Photograph by author.

Although the ship has been secured since Norwegian Cruise Lines purchased the ship in 2003, vandals had taken their toll when she sat largely unattended during the late 1990s. Shooting out portholes was a popular pastime among trespassers. Photograph by author.

A phone switchboard, probably dating from the 1950s, sat jammed against the wall. It might have been this same one that connected the daily phone calls of William Francis Gibbs, the ship’s designer, to Commodore Harry Manning to find out how the ship was performing. Or to his wife Vera Cravath Gibbs, a frequent traveler on the ship who supported her husband throughout the long process of the design and construction of the finest and fastest ship of the world.

William Francis Gibbs, who had spent nearly forty years dreaming of creating a great liner, not only closely supervised every aspect of her design and construction from 1950 to 1952, but closely tracked her performance from his office. Every time she docked in New York, he was there to greet her. For him, this ship was not just a work of engineering, but also a work of art and an extension of his soul, his magnum opus after a successful forty year career as a naval architect. He died the day after one of her arrivals in New York, on September 6, 1967. Almost exactly two years after her creator died, the ship’s career died too, and since then has endured 40 years of lay-up, neglect, stripping of her interiors, and a few owner bankruptcy sales. Yet Gibbs’ creation still miraculously endures in the city of his birth.

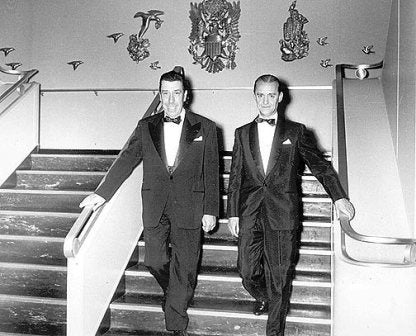

The artist and his masterpiece.

http://www.ss-united-states.net/WebPages/PagesGibbs.htm

Next was the march to the closest staircase, which took us up to her passenger decks. The crew corridor leading to the tourist class staircase at the forward end of the ship was almost pitch-black. Plywood ramps were in place to prevent people from tripping over the protruding floor lips of the watertight doors. A glass-encased crew bulletin board, its last announcements removed decades ago, shimmered from of our flashlights. Former crew spaces were on the left side of the corridor. The pedestals of long-gone tables and chairs stuck up from the floor. In one crew lounge, however, one forlorn swivel chair still remained bolted to the deck.

While passengers enjoyed spacious luxury and fine dining on the upper decks, the ship’s crew would enjoy their precious leisure time in these cramped, dark spaces deep in the bowels of the great ship. Often away for months at a time, the thousand-strong crew was divided into two groups: seamen and the hotel department. The seamen consisted of the officers, engineers, and mechanics, and their duty was to make sure the ship was properly maintained and operated. The hotel department was a small army of stewards, gourmet chefs, bellboys, pursers, bartenders, and waiters. Their job was to ensure the comfort of the of ship’s 2,000 passengers. In first class in particular, wealthy repeat passengers would often not just request their favorite suite, but also their favorite cabin steward. This was an arrangement that not only suited the passengers, but also the steward, who could expect generous tips and presents at the end of the four day voyage.

A crew companionway deep in the bowels of the ship. To the right is a glass-encased bulletin board for announcements to the 1,000 person crew of the great ship. Photograph by author.

Members of the crew pause for a photograph while the ship is docked in Southampton in 1956. Photograph by Joe Rota. http://www.ss-united-states.com/galleryvt.html

The S.S. United States’ 2,000 passengers were divided into three distinct passenger classes—first, cabin, and tourist—each class with its own public rooms and deck spaces. No longer practiced on today’s cruise ships, this arrangement was a hold-over from the Victorian era, and was particularly rigid on British liners such as the Queen Mary, where various social classes were not supposed to interact with each other. The S.S United States was one of the last three class liners to be constructed. By the 1950s, this elitist arrangement was becoming not only outdated, but also increasingly socially repugnant, particularly among American travelers. The next large ocean liner built after the S.S. United States, the French Line’s S.S. France of 1962, was divided into only two classes: ultra-luxurious first class and the much more capacious and informal tourist class. Aboard the S.S. United States today, the partitions and barriers separating the three classes and the crew areas from each other have all been removed, allowing full and unencumbered access for the visitor, although it is best that he brings a set of deck plans and a powerful flashlight.

The tourist class staircase, located at the forward end of the ship, goes up eight decks to the bridge area at the top of the vessel. The U-shaped staircase twists and turns through more areas of dimly lit, unidentifiable public areas and former cabins. In the mid 1990s, in anticipation of being refitted at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, the great ship was towed to Turkey and stripped of all of her asbestos-laden interior partitions and paneling. One of the great flaws of Gibbs’ fireproof design was the heavy use of asbestos, used extensively in shipyards prior to the 1970s. The stuff was everywhere; in wallboards, insulation, floor tile, and pipe insulation. Now stripped down to bare metal, the ship’s interiors are painted a sickly industrial yellow. Still clearly visible on the bulkheads are the stenciled lettering and handwritten marker notes used to aid the Newport News shipbuilders during the ship’s construction from 1950 to 1952.

A view from the tourist class staircase on the climb up to the bridge. Photograph by author.

As we climbed higher, natural light started to filter into the stairwell from the large windows of the promenade deck and upper deck public rooms. The first class observation lounge and the ballroom were quickly visible as we continued our climb up the tourist class staircase, as the class-dividing partitions have been removed. The interior structural steel and aluminum metalwork, painted industrial yellow, looked as if it all had just been welded into place yesterday. Finally, we reached the top deck just forward of the first funnel, where the bridge and navigational areas of the ship are located.

A commanding view from the bridge. Forty years ago, the Commodore of the United States Lines would have gazed at churning seas, as his giant ship, carrying 3,000 souls, thundered ahead at 35 knots. The height of the breakwater indicates the size of waves Gibbs anticipated his ship would be facing on her North Atlantic crossings. Photograph by author.

The bridge in 1952, showing the ship’s wheel, engine room telegraphs, and navigation equipment. www.artymesia.com

Considering the size of the S.S. United States, the bridge area is remarkable small and spartan. The bridge originally had no wood fittings or polished brass instrumentation. Everything was painted military gray. All of the original instrumentation, including the ship’s wheel, navigation equipment, and engine room telegraphs, have been removed, leaving pathetic raised stubs and severed wiring on the floor. The bridge, like all other parts of the ship, has been stripped down to bare, yellow-painted metal. The windows are streaked with grime.

While venturing out onto the port side wing bridge, I discovered that the floor had rusted out. If I had not looked more carefully, I could have plummeted several stories into the murky Delaware River.

View from the officer’s promenade, looking aft towards the second funnel and Camden in the distance. Photograph by author.

Perched at the very front of the superstructure and raised two decks above the passenger spaces, the bridge presents the viewer with a commanding view over the great ship’s bow. Here, Commodore Harry Manning would supervise the operation of the fastest passenger ship in the world and the largest ship built in the United States, holding the lives of nearly 3,000 people in the palm of his hand. Someone once compared handling the S.S. United States to jockeying a thoroughbred racehorse: extremely fast and responsive, but also a tad skittish compared to her contemporaries [ii].

The forecastle, located in front of the bridge and once in several layers of protective green paint, is almost completely caked in rust. This area, which served as a recreational space for the crew as well as for freight handling, was built to take the full-brunt of the Atlantic Ocean while the ship was underway. Unlike today’s top-heavy cruise ships, which retreat to the nearest port at the slightest hint of foul weather, the S.S. United States was constructed to press onward at full speed while being lashed by North Atlantic gales. Even a ship as large and well-designed as this one would roll and heave in bad weather. During rough winter crossings, gigantic waves would roll over the ship’s bow and smash into the breakwater, meant to protect the bridge and superstructure. For unseasoned passengers, winter storms in particular could be terrifying. Even for experienced voyagers, seasickness could make life miserable. Bad weather was particularly unpleasant for the several hundred students and immigrants traveling tourist class, situated in the bow section of the ship, where motion was most pronounced.

Looking forward from the base of the second funnel. The port side wing bridge is visible. Photograph by author.

The remains of a shuffleboard court on the first class open promenade. The lifeboats that once lined deck been sold for scrap long ago. Photograph by author.

During calmer summer crossings, the open sports decks were beehives of activity for her first and cabin class passengers. Unlike the wood decks of older liners, the decks the S.S. United States were metal coated with a durable green, macadam-like walking surface, once again part of her designer’s intention of creating a completely fireproof vessel. Here, passengers would play shuffleboard and deck tennis, as well as lounge around in deck chairs while watching the ocean race by. On sunny days, the ship’s orchestra would set itself up outside and serenade the passengers both on the first class sun deck and the cabin class raised platform.

Today, these once bustling decks are cracked and desolate, covered with paint chips fallen from the ship’s funnels and shards of broken glass that crunch underfoot. A lone shuffleboard court, its painted white lines barely legible and its surface pockmarked, manages to survive on the upper sports deck. All of the ship’s aluminum lifeboats, which once buffered the sports decks from the wind and spray of the North Atlantic, have long since been removed and sold for scrap.

The iconic red, white and blue funnels were a favorite of photographers during the ship’s heyday. The finned configuration was to prevent smoke and soot from soiling the well-dressed passengers below. www.artymesia.com

The second funnel, looking aft from the officer’s promenade. Photograph by author.

View aft over the fantail, across the Delaware to Camden, New Jersey. This was once the cabin (second) class sports area. On warm summer crossings, one of the ship’s three Meyer Davis orchestras would play on the raised deck section. Photograph by author.

After this quick exploration, I set up the laptop in the former officer’s lounge on what seems to have been an old metal ping pong table, the only stick of furniture remaining in the space. Since there had been no power on board for forty years, I had to rely on the computer’s battery as the video footage cards were fed to me by the production crew. As I was downloading the video cards being fed to me by the cameramen, the lighting crew led by artist Robert Wogan started to assemble a series of massive lighting units that were powered by generators brought on board. Wogan had lit the ship up several years ago as part of an effort to raise awareness about the ship in Philadelphia. Now, he was going to be lighting up the ship even more spectacularly than before for two successive nights for this documentary filming.

After a couple of hours and as the sun started to set, the cameramen had finished shooting their footage on board and we had to leave the vessel to prepare to shoot the nighttime exterior shots. During this interlude, I took a quick run around a few of the ship’s once-luxurious first class public rooms on the promenade deck, camera and flashlight in hand.

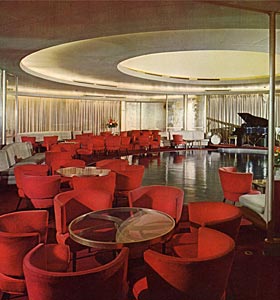

The ship’s interior designer, the sophisticated Dorothy Marckwald, was charged with designing interiors that were modern, dramatic, colorful, and utilized no wood or flammable materials. When asked why her interiors were did not hide exposed rivets and stanchions, Marckwald responded: “”The United States is a ship, not an ancient inn with oaken beams and plaster walls.” [iii] Today, almost all of Marckwald’s work is gone, but I still wanted to see these once-dramatic seagoing spaces.

First was the first class observation lounge, spanning width of the ship and defined by tall, rectangular windows that once provided stunning views of the ocean sweeping by for the ship’s most privileged passengers as they read magazines and played bridge and canasta. This quietly sophisticated room was once defined by elegant blue leather chairs and sofas, floor mounted lamps, dramatic ceiling lighting, and jewel-like maps of the world mounted on concave walls.

The First Class Observation Lounge. This sophisticated space was a place for reading, card games and quiet conversation. www.ssunitedstatesconservancy.com

The same space today. The partitions separating the first class observation lounge from the tourist class library and theatre have been removed. Photograph by author.

Next was the cavernous first class ballroom, located amidships, where the motion of the ship was least apparent. In this once sleek space, the epitome of 1950s chic, famous couples such as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and Prince Ranier and Princess Grace of Monaco, and John and Jackie Kennedy would foxtrot and tango to the accompaniment of one of the finest dance orchestras on land or sea. It was topped with an elegant dome and enlivened by intricate, shimmering etched glass panels. Today, the band has packed up, the bar is closed, and the laughter and toasts have ceased. Only the dance floor remains as a reminder of its glory days.

The first class ballroom. At night, the dramatic lighting and the glass panels gave the room a shimmering effect. www.artemysia.com

Salvador Dali in the first class ballroom, 1957. Photograph by Joe Rota.

http://www.ss-united-states.com/galleryvt.html

The first class ballroom today. Only the dance floor remains. Photograph by author.

French actor Fernandel descends the first class grand staircase, dressed for dinner. The American decorative motifs were molded from aluminum in keeping with the ship’s fireproof “no wood” design. Photograph by Joe Rota. http://www.ss-united-states.com/k1img/rota16.jpg

The first class grand staircase today. The doors to the enclosed promenade deck can be seen on the right. Photograph by author.

Time was running short. I pushed my way through two aluminum double doors to the port side enclosed promenade deck, whose handles were still labeled “push” in stylized 1950s lettering. I looked aft down a space about 15 feet wide and 400 feet long. There was no time to walk its length, but tried to imagine the space filled deck chairs, strolling passengers and uniformed stewards with food carts serving tea and hot boullion.

Doors to the first class enclosed promenade on the port side. Some appears to have kicked in one of the glass panes. Note the sheer of the ship’s deck. Photograph by author.

The port side first class enclosed promenade. Forty years ago, this space was lined with deck chairs and pushcarts serving hot boullion and tea. It was a boulevard at sea for the American and European social and business elite. Photograph by author.

I looked down at my boots and to my horror I saw a large pile of feathers. Apparently a number of pigeons had found their way into the enclosed promenade through one of the broken windows. Unable to find their way out, they had starved to death.

As night fell, the production crew set up lights and microphones in front of the great ship in preparation for the visual and musical climax of the day. Skunk Baxter, the guitarist for Steely Dan, was to play “America the Beautiful” in front of the S.S. United States as part of the concluding sequence of the documentary. As the light faded and the wind started whipping across the Delaware River, Wogan’s enormous floodlights slowly and dramatically lit up the two great red, white, and blue funnels, the forward mast, and the bridge. Baxter’s soft electrical guitar strains began drifting across the water and wafted around the great ship at rest. A few passersby on Delaware Avenue peered through the chain link fence and watched the scene.

For the production crew and the board members of the S.S. United States Conservancy, this was one last moment to be savored. Would this be the last time she was ever going to be illuminated? Will her decks and lounges once again resonate with the sound of music and laughter as she speeds into the darkening night? Despite decades of abuse, America’s great flagship still spoke with amazing eloquence to all of those who took the time to listen to her story. It was at that moment I realized we were truly facing true greatness and beauty–something not often seen in today’s society. The lighting, the music, and the visual magnificence of the ship combined to form one those rare moments that allows one to deeply savor a great triumph of engineering innovation and artistic inspiration, such as the Brooklyn Bridge or the Empire State Building. Although faded and careworn, this great American lady was able to touch the hearts of everyone involved in producing this documentary, and will tell her full story to the world when the documentary airs on PBS in early 2008.

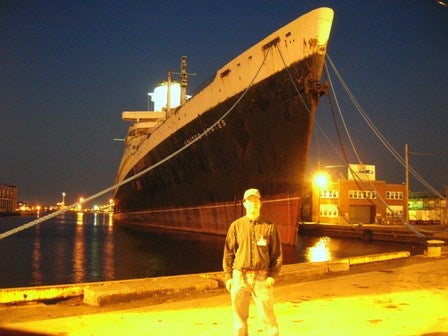

The author in front of the ship as Skunk Baxter of Steely Dan plays “America the Beautiful” for the PBS documentary filming. Wogan’s s floodlights have been switched on, illuminating the stacks and bridge of America’s flagship for the first time in years. Photograph by author.

A view of the illuminated bridge and funnels from the dock on April 25. Photograph by author.

The forward funnel fully illuminated on the night of April 25. In the years to come, her lower decks might once again be lit up and resonate with the sounds of laughter, the clink of cocktail glasses, and the strains of beautiful music. Photograph by author.

The S.S. United States at night, dry-docked and fully-illuminated in Newport News, Virginia for her annual overhaul.

http://www.ss-united-states.com/paxmilE4b.html

LINKS:

S.S. United States Conservancy Website

www.ssunitedstatesconservancy.org

Director Robert Radler’s photographs of the ship taken in 1975 in Norfolk, Virginia. She had been laid up for 6 years and was still almost completely intact.

http://www.ssunitedstatesconservancy.org/Radler.html

Producer Mark Perry’s collection of rare film footage of the S.S. United States and other liners.

http://www.shipgeek.com/navigation.htm

Inquirer article on the filming of the PBS documentary, published April 26, 2007.

http://www.philly.com/inquirer/local/philadelphia/20070426_Liner_back_in_the_spotlight.html

Website for the upcoming PBS documentary. Under construction.

[i] Interview with Greg Norris, Vice President, S.S. United States Conservancy, March 26 and 27, 2007.

[ii]S.S. United States Conservancy: History

http://www.ssunitedstatesconservancy.org/History.html

[iii]A Woman’s Touch: The Seagoing Interiors of Dorothy Marckwald

http://home.pacbell.net/steamer/marckwald.html

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.