Outgoing Philly teachers cite frozen wages as reason for quitting

Cassidy elementary school guidance counselor Tara Tyler has reached a breaking point. She’s a single mom who’s felt the pinch of the rising cost of living, but meanwhile, her job feels more stressful by the week, and her pay has flatlined since 2013.

“I put in all my time with other people’s children and it’s not being compensated for,” she said. “And at the end of the day, I try to explain to my son that I’m doing it for him. He doesn’t see it. He doesn’t understand it.”

So after nine years in the district — all at schools in impoverished neighborhoods — she’s submitted her resignation letter.

“I have the skill set where I can get other employment,” she said, unsure of what’s next, but confident in her abilities.

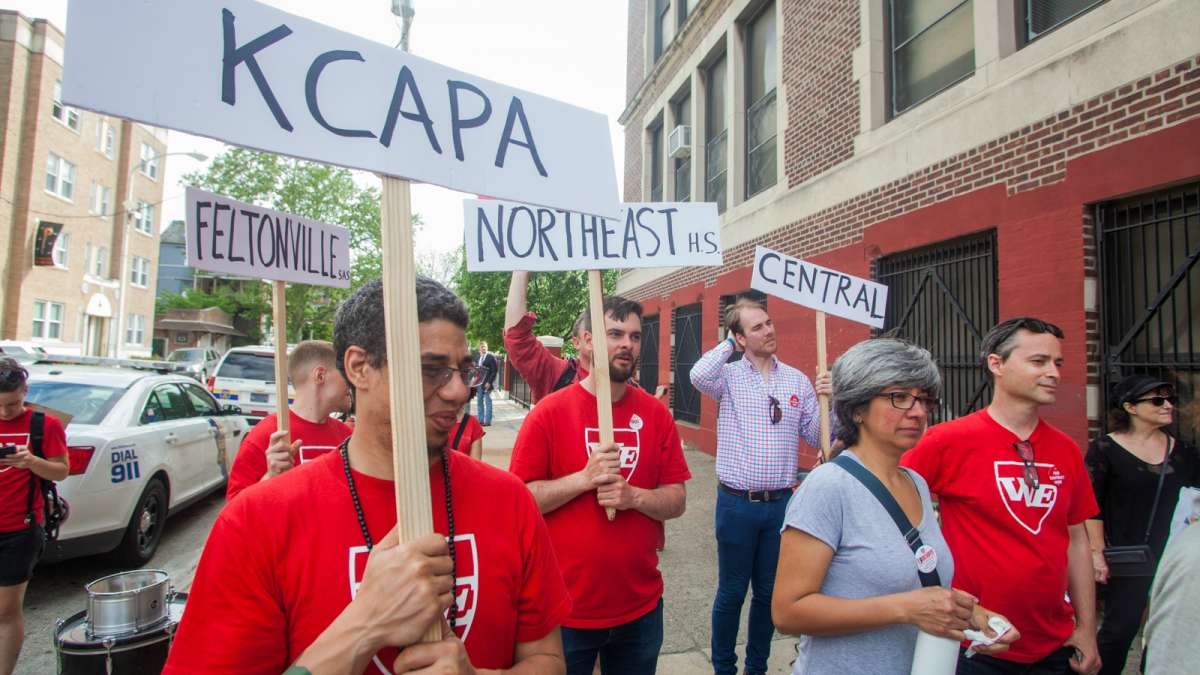

Tyler spoke about her experience on Monday at an “educator exit” rally hosted by the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers outside of West Philadelphia’s Lea Elementary. The Philadelphia rally was one of thousands being held worldwide by unions to mark the annual International Workers’ Day.

PFT members have been working under the terms of a pact that expired nearly four years ago. Since then, teachers, counselors and nurses haven’t been getting the raises they’d been scheduled to receive for years of experience or continuing education credits.

For some, especially younger teachers who pursued advanced degrees, this amounts to tens of thousands of dollars of expected income that has yet to — and may never — materialize.

“We have teachers who have been in the district for five years who are still being paid on the first year salary rung,” said union president Jerry Jordan. “They have been more than patient.”

Emily Cashin is also leaving the district. After teaching Spanish for eight years at Carver High School of Engineering and Science, she’s decided to pursue a masters in business administration.

“I love this city and I love my students. I love their potential and I have hope for their future. But I cannot be my best self or have any significant influence in this pigeonhole of a career,” she said. “I will find another way to support teachers in the future, but I will not suffer this humiliation and disrespect any longer.”

The district downplayed the effect that prolonged contract negotiations are having on teacher turnover, citing a year-over-year teacher retention rate of 90 percent.

“Our teachers are choosing to stay and teach in Philadelphia,” said district spokesman H. Lee Whack.

Vacancies, though, have been a persistent problem in district schools in the past few years, specifically in the schools serving the city’s neediest students.

In some cases, this has meant that the children who need the most support have been educated by a patchwork of teachers and substitutes who sometimes aren’t certified in the subject matter.

Both the PFT and the district declined to discuss the specific points of contention in their stalled contract talks. But it’s been long known that the district has been asking for PFT members to begin making contributions to their health insurance premiums.

On average, teachers in Philadelphia public schools earn less than their counterparts in the surrounding counties. This is a statewide trend driven, in large part, by a funding system reliant on local property taxes.

Teachers in Pa.’s poorest districts, such as Philadelphia — which are concentrated with students with very high needs — are paid roughly $15,000 less, on average, than educators in the state’s richest districts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.