World weather libraries offer historic clues about climate

Listen 5:58

Around 1910, observers prepared to launch this Weather Bureau kite, which would be anchored by the kite-reel house in the background. (Photo via NOAA Photo Library)

Whether it’s an especially hot or cold day – or mild or unmemorable one – the weather reports coming through the radio, the internet and the nightly news all get collected in real time by meteorological forecasters. But then, those records find their way to a central data center, or rather, a weather library of the world.

The three main ones are in Hamburg, Germany, Obninsk, Russia and Asheville, North Carolina. Analysts are learning a lot from what’s stored there, such as what to make – or not make – of a really hot day.

Compiling weather data

Derek “Deke” Arndt says “the Russians do some really neat things with hydrological data,” a crew in London specializes in tracking sea surface temperature. Meanwhile stateside, “we’re pretty good at global surface temperature.”

Arndt is chief of climate monitoring at the National Centers for Environmental Information, a special branch of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The central weather data center there contains servers filled with meteorological information coming in from satellites and other sources from across the globe.

“The operational weather community really gets along well internationally,” Arndt said. “And so when they have shared this data through the World Meteorological Organization, it ends up getting routed here after it’s served its first purpose, which is to inform forecasts to protect life and property.”

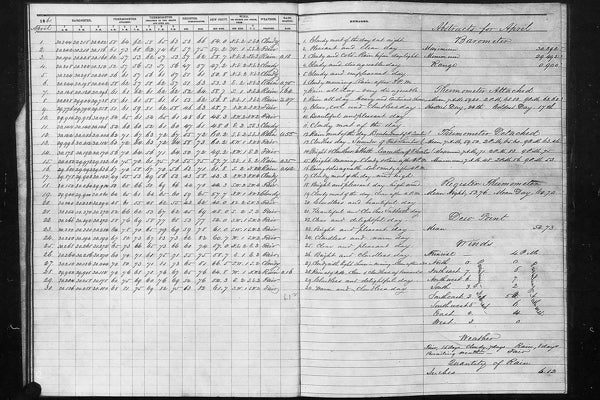

And like any good keeper of information, the library also has a locked room in the basement. In it are rows of boxes filled with handwritten weather observations going back decades and beyond.

“Whatever school you went to, [imagine] the old, old part of the library. Except instead of old books, it’s old old boxes of old old paper and some old weather instruments,” said Arndt.

In the old days, farmers, ranchers, dam operators and others would fill out a form and mail it to the weather service.

“So all of the observations that have been made officially in the last century or two, and we even have some going back to Thomas Jefferson, they find their way here and they live in active retirement.”

What climate scientists make of weather records

Arndt stresses that there is a very timely reason for maintaining this old weather information.

“So it’s just like any good story in anybody’s life. You don’t know where you’re going unless you know where you’ve been. And science works that way too,” he said.

One hot or cold day doesn’t mean much in itself. Arndt conjures up an old saying that reflects the difference between climate and weather:

“Weather is what you get. Climate is what you expect.”

In other words, day-to-day weather conditions fluctuate for all sorts of reasons. But collected over time, scientists like Arndt can start to glean patterns and trends that reflect a bigger view about climate.

Arndt’s group has been mining through that weather data and recently found that this past June, for example, was the third warmest worldwide on record. It’s not just a one-off: June has been warming for many years.

Several hundred miles north of Asheville, Michael Mann, director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State, has been running statistics on this type of weather data. He, too, has identified bigger climate trends.

“We’ve seen a doubling of record heat here in the United States over the past half century,” Mann said. “And so what we’re seeing then is not the individual rolls of the dice. The individual rolls of the dice, that’s weather. But when we see that the dice have been loaded so that sixes are coming up twice as often as they should, that’s sort of an analogy for what we’re seeing with climate change. We’re seeing the loading of the dice.”

Important differences between weather and climate

Mann is cautious when discussing weather and climate. He says it’s important to avoid conflating the two. Anecdotes and memories about weather at any given point in time are powerful. It’s human nature to attach one thing to some bigger trend. It’s probably easier to remember that really big snowstorm as a kid with snow up to your chin, or the one last year that trapped you inside for two days. You probably aren’t taking note of a normal day.

But over time, Mann is discovering important changes in those weather patterns, and more specifically, how they have gotten more extreme over time. The dice keep turning up sixes, he says, pointing to extreme events in recent history, like the major floods in Louisiana and West Virginia, the massive fires in California and the droughts in Oklahoma and Texas.

“What is true is that when we start to see unprecedented weather events and record floods, record length heat waves, and record hurricanes, if you look at the underlying science of climate and climate change, what it tells us is that in each of these cases we do expect to see more extreme events of those sorts as we continue to warm the planet,” Mann said.

Meanwhile, back in North Carolina, Deke Arndt says all of the climate insight that scientists are finding out now is critical information for our planet. For him, that makes those weather records collected decades, and even centuries, ago by farmers and others even more special.

“I would love to go back to, you know, a farmer in Nebraska and say, ‘Thank you for what you have done. You know, you may not know it now, but 80 years from now there’ll be this big topic of conversation called climate change…and the numbers that you wrote down diligently every day are going to help bring more clarity to that conversation.’ I really wish I could invent a way to go back and thank people for what they’ve done.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.