This week in science: Philae landing, mouse control and cat genes

Listen

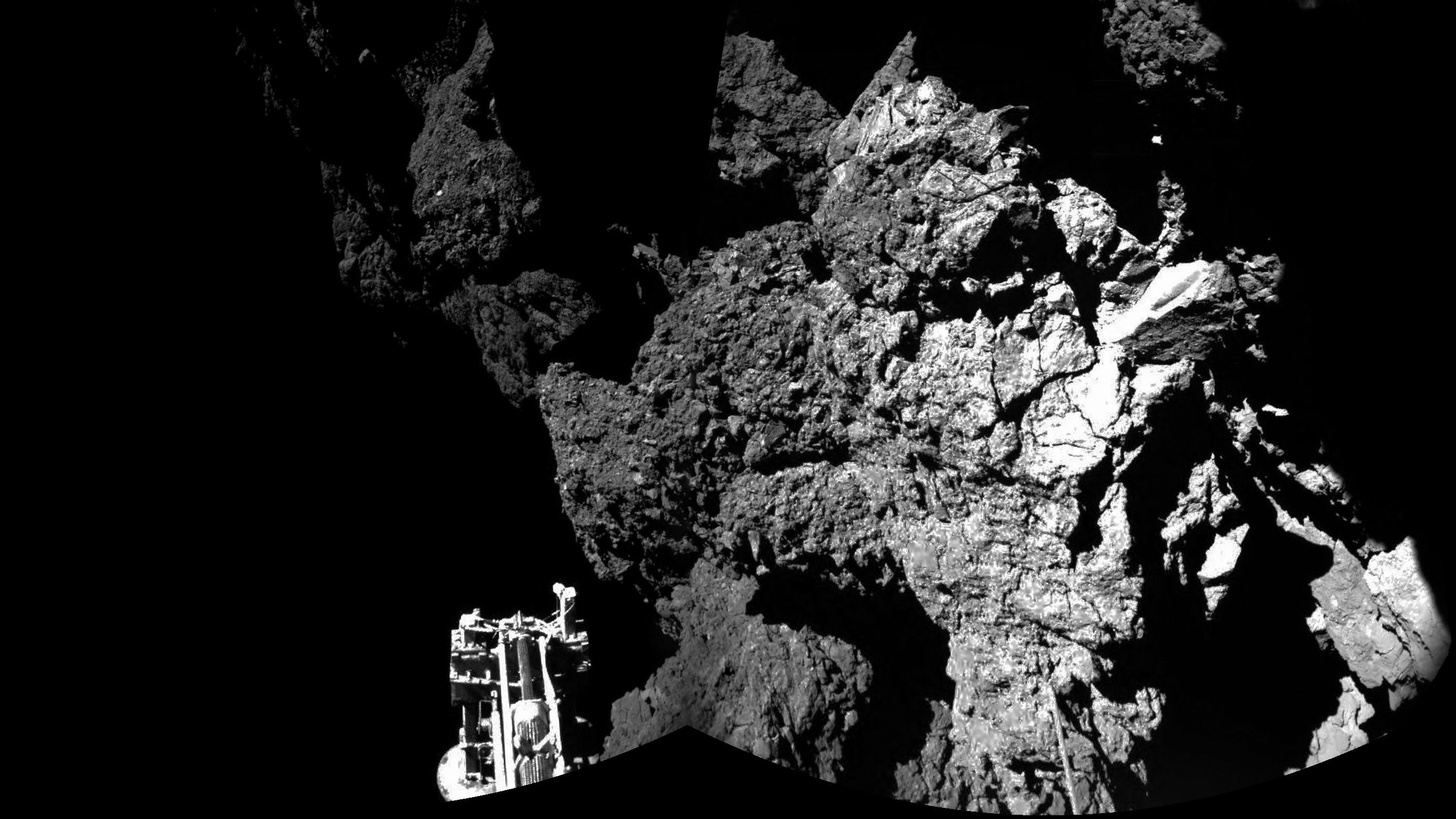

Rosetta’s lander Philae is safely on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

It’s been a busy week in the science world, perhaps best symbolized by the explosion of the “#cometlanding” hashtag on Twitter. Kerry Grens, Associate Editor at The Scientist magazine, explains the Rosetta spacecraft’s comet exploration mission and other top science news from around the globe.

The Philae has landed

Earlier this week, the Rosetta, a long range unmanned spacecraft, released the space probe Philae, which successfully landed on the surface of the comet Churyumov–Gerasimenko, near Jupiter. Rosetta has been in space since 2004, as part of a European Space Agency mission to make the first successful landing on a comet in history.

“The goal of the mission is to drill into the comet, to take pictures and other measurements,” said Grens. “Scientists are very interested in the molecules on the interior of the comet, particularly water and organic molecules, which are the building blocks of life.”

Comets are bits of cosmic leftovers from the formation of the solar system billions of years ago. Grens says scientists believe that learning more about their composition could reveal clues about how planets formed and life evolved.

“There’s this idea that comets had smashed into the Earth way back when and brought some of these molecules to the planet, perhaps seeding the planet with the molecules that would go on to form life,” said Grens.

For now, the world has been more interested in the photos Philae is beaming back to Earth, along with loads of other data from its onboard sensors and chemistry lab. It will continue to do so for about a year, or at least until dust from the comet prevents its solar panels from functioning. Neither probe will return to Earth — both will spin out of the solar system along with Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

Mouse control

Researchers in Zurich this week revealed that they had developed a new bionic implant they are testing on mice that is controlled by human brainwaves. It might sound a little like something out of mad scientist’s laboratory, but it’s process could hold groundbreaking applications for an early field of technology, called optogenetics. The implant is made from human cells and an LED light. The cells are genetically engineered to produce a protein when they sense that the light has turned on, a process controlled by a switch that is remotely connected to a computer that can read human brainwaves.

Human test subjects were told to concentrate on a light or image that produced certain brainwaves, triggering the implant.

“The people perform this mental task, the brainwaves will then be interpreted to turn on this light, and then the light will cause the genes to produce this protein,” said Grens.

She says meanwhile the mouse is just “hanging out,” alive, in a contained area.

So what’s the point?

“The idea is that you could have a therapy based on this design,” said Grens. “So for example, people who are unable to communicate, who may be immobilized, paralyzed and can’t speak, but may be in pain, perhaps they could have an implant that delivered a painkiller. That they could control turning it on by performing a mental task.”

She added that while optogenetics is still in its infancy, the field has advanced with remarkable speed, and could lead to more complex “mind controlled” devices down the road.

Cat genes

Every cat owner has, at one time or another, gotten the feeling that their pet was at best indifferent to the demands and interests of their human counterparts. Well, an international effort at mapping the genome of common house cats has revealed that it’s not entirely cats’ fault that they are so, well, catty — they only evolved the ability to tolerate humans a few millennia ago.

“Cats became domesticated around nine or ten thousand years ago and it looks like several genes related to temperament and personality underwent some adjustments, perhaps not surprisingly,” said Grens.

She said that researchers discovered differences in the genes of house cats when compared to their wild relatives, specifically those related to aggressive behavior, learning and memory. However, superficial traits like fur texture and color were also found to have evolved over time, likely as a reaction to humans preferring (and breeding) cuter, cuddlier cats, at the expense of their wilder peers. While the new information is intriguing, but it could also hold clues for treating diseases that afflict both humans and cats.

“To understand cats’ genome also means to potentially understand human diseases that may have similar genetic underpinnings,” said Grens. “And then, of course, any diseases that affect cats, because as our companion animals, that’s important to us as well.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.