This computer pioneer was a bit ahead of his time

Listen

John Blankenbaker

John Blankenbaker opened the door wearing perfectly pleated slacks and a deep red sweater, shoes polished, his hair trimmed into a buzz cut.

The Navy veteran’s home in suburban Pennsylvania is just as orderly as his look, which, considering his deep understanding of computer logic, shouldn’t come as a surprise.

The 86 year old’s first work on computers came in 1951—after Naval service and degrees at Oregon State—as an intern at the Washington-based National Bureau of Standards. There, he got a close-up look at the room-filling government computers of the day, including the SEAC machine, though he says the software program he wrote for the machine never worked quite right.

Undeterred, the experience sparked a career in computers that would span two decades in the private sector. Then, he decided to branch out.

“It had been an idea that was percolating in my mind for several years, until 1970, when I had an opportunity to do something on my own. And that was the start of the Kenbak Computer,” he says.

Living in California at the time, and with a bit of money at his disposal, Blankenbaker launched the Kenbak Corporation in his garage.

“In order to make it a little more pleasant, we put panelling up and made an office and there was a workbench, oscilloscope, drill press. And I had started in September of 1970, and by the next spring, I had a working computer.”

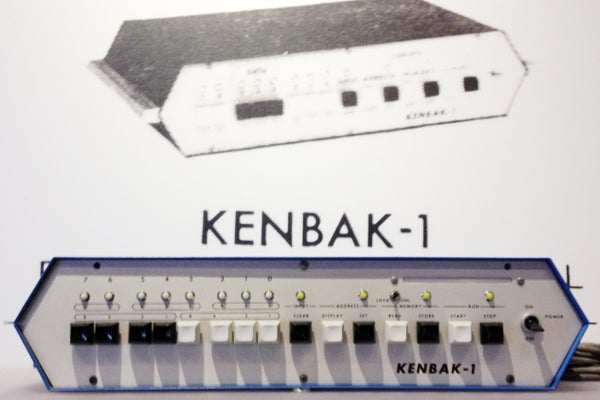

While the Kenbak-1 worked, it couldn’t be confused with a modern computer. It had no monitor, no keyboard, no mouse or disk drive. Looking more like a VCR than laptop, it sat 18-inches wide and about 4-inches tall, with a row of lights and switches gracing the front panel. Those were the inputs and outputs used to enter commands and run programs.

The Kenbak-1. (Kathryn Greenhill/Wikimedia Commons)

The novel thing about the Kenbak wasn’t its memory (256 bytes), advanced integrated circuitry or processing speed. It was that it arrived in one piece.

“It was a fully assembled and tested computer,” says Blankenbaker. “Yes, people were buying parts and were building their own computers. And in that sense, they had their own personal computer. And some of them were quite advanced machines, but they were not commercially produced at all.”

The Kenbak-1 wasn’t trying to compete on speed or processing power. It was meant to be an introductory unit; a teaching machine through which you could learn basic computer programming.

And basic is the key word.

For $750, just about the best thing the Kenbak-1 could do was tell you what day of the week a randomly selected day fell on.

“So in that case, the input was first you entered two digits for the last two digits of the year, two digits for the month, two digits for the day, and the answer was displayed in eight lights,” he explains. “Light Number Zero would light if there was no such day. And Light One for Monday, through [Light] 7 for Sunday.”

Blankenbaker unveiled his machine at a conference in 1971, where he asked people in the audience for their anniversary. He would input it, get the right light to glow, and prove the Kenbak-1 actually worked.

The response was warm enough.

“Then that summer, we prepared to build more. I raised some money. And worked on selling some and by September of 1971, one year after the start, I had sold two computers and felt confident enough to move to larger quarters,” he says.

“However, it was not a well-placed optimism.”

He went ahead and built 50 units, but it’s worth pointing out right here that by his own admission, Blankenbaker was not a business guy. He was a tech guy.

His mistake was trying to sell computers to community colleges that he thought could use it as an educational tool. There’s nothing wrong with that idea, except schools don’t make big purchases without lead time. A budget cycle, sometimes a very long budget cycle, gets in the way.

Blankenbaker didn’t focus enough on the private market, where he might have made more immediate sales.

“Well, after a year, it was obvious we weren’t making enough money, and so it slowly diminished, and I had no plans to go beyond the 50, and I went back to work for someone else. And it sort of just died.

“The investors took their lump, and that was it.”

There would be no Kenbak-2.

Still, the experience doesn’t seem to taste too sour to Blankenbaker.

“Oh no, I have no regrets,” he says. “Not at all. It was an enjoyable experience. It could have been more successful financially, but I didn’t go into this as a financial endeavor, or to make money. I just wanted to bring computing to more people, and I certainly was a pioneer in showing the way.”

Blankenbaker has held onto a banker’s box full of memorabilia, including an original motherboard and a stack of yellowing stationery for the Kenbak Corporation. His computer was honored in 1987 with the title “First Commercially Available Personal Computer” by the Boston Computer Museum, and other awards line his mantle.

Last year, he auctioned off his last two assembled Kenbak-1s. He says they brought in, combined, enough money to redo his basement.

“I’ve done many things in my life, this is just one of many,” he says. “And some of the other things I’m as equally proud of. So, I’m happy. I will be departing this life before long, and I’m content.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.