Spreading the legacy of Fred Korematsu, U.S. internment camp objector

Japanese-American's case referenced in U.S. Supreme Court opinion allowing President Donald Trump’s ban on travel from several Muslim-majority countries

Listen 2:34

Karen Korematsu addressed a group of teachers about her father's legal battle against internment during World War II. Her talk was given at the nonpartisan Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge. (Brad Larrison for WHYY)

Fred Korematsu was a 23-year-old Californian in 1942 when — unlike his parents — he refused to comply with then-President Franklin Roosevelt’s order to report to an internment camp for Japanese-Americans.

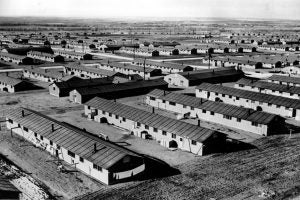

After he was caught and jailed, he challenged his imprisonment on constitutional grounds. The high court disagreed and, in 1944, upheld the mass incarceration of some 120,000 Japanese-Americans in 10 such camps, most of them in the West.

But this June, 73 years after Korematsu’s landmark case was decided, it regained prominence in the high court when Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that Roosevelt’s order was “objectively unlawful and outside the scope of presidential authority.”

Roberts’ repudiation of Roosevelt’s order wasn’t a new ruling in Korematsu’s case, though. It was included in his majority opinion supporting President Donald Trump’s ban on travel from several Muslim-majority countries.

In the travel ban opinion, which the justices decided by a 5-4 vote, Roberts wrote that his predecessors who decided Korematsu’s case were “gravely wrong’’ and had been “overruled in the court of history.”

Korematsu’s conviction was overturned in 1983, and he later received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

He died in 2005 at the age of 86, but his daughter, Karen, who runs an education institute named for him, said he would have been infuriated that his argument would be effectively endorsed in a ruling about a new presidential policy that critics contend is anchored in religious bigotry.

“He would be very sad and he would be very disgusted,’’ Karen Korematsu said in an interview Friday after speaking to about 75 teachers at the nonpartisan Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge. “He would feel, that’s why he fought all those years, so something like this wouldn’t happen.”

Korematsu said that while her father was righteous, he was a peaceful man who never became bitter, even though many Japanese-Americans resented his stance and ostracized him.

He aspired to be a Realtor, but his felony conviction prevented him from getting a license. So he worked as a draftsman and, with his wife, raised Karen and her younger brother, Ken.

He was a leader in his Bay Area community’s Lion’s Club, Boy Scout troop and Presbyterian church. She recalled him as a kind and understanding father, but joked that he “did get angry once when I didn’t want to practice my clarinet.”

History, she suggested, “should remember my father as a man who made a difference in the face of adversity and believed that being an American means to support citizens and noncitizens. He represented all Asian-Americans and those people being marginalized.”

Getting the story out

Amy Merkley, who teaches middle school civics, English and world cultures near Seattle, listened intently to Korematsu’s lecture. She said more Americans need to know the story.

“It’s important we know our history, the good, the bad and the ugly,” Merkley said. “There’s a lot of focus on volunteer monuments coming down, but there’s more to our story than just that struggle.”

Although Korematsu is hardly a household name in America, Merkley said she saw a documentary about him recently.

“The courage it took to go against, not only the American government, but his own family members” awed Merkley. “The courage to stand up for what is right no matter that people around you don’t support it. It’s just an honor to hear about this man and see that his daughter is continuing his story, his legacy. It’s incredible.”

Korematsu’s institute has created a curriculum that Merkley and other teachers can use to educate their students about the internment camps and other civil and human rights abuses.

The Fred T. Korematsu Institute’s official mission is to promote “the importance of remembering one of the most blatant forms of racial profiling in U.S. history, the incarceration of Japanese-Americans during World War II, by bridging the Fred Korematsu story with various topics in history, including other civil rights heroes and movements, World War II, the Constitution, global human rights and Asian-American history.”

‘There’s no floor, it’s just dirt’

The Korematsu case is a legendary, notorious one in U.S. history.

The saga started during World War II in February 1942, about two months after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Under Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, Japanese residents, including citizens, were ordered into 10 internment camps in California and others mostly west of the Rockies.

Korematsu, whose parents ran a plant nursery, would not turn himself in to authorities. He was arrested, jailed and convicted of a felony for failing to report for evacuation.

Korematsu was one of several who fought the constitutionality of Roosevelt’s order. During this time, he was detained at an assembly center for Japanese-Americans near San Francisco where he was held in a horse stall.

“There’s no floor, it’s just dirt, so the wind was blowing through that, and it was cracks all around the walls, and there was a light bulb up there, one light bulb on the ceiling and that was it,” Korematsu later said a PBS documentary.

He later spent time at a camp in Utah.

Starting in 1944, before internment ended, a farm in Seabrook, New Jersey, employed more some 1,000 of those held in camps under a work-release program. That number swelled to more than 2,500 after the war ended in 1945, and many of those workers ultimately settled in New Jersey.

‘Legalization of racism’

In December 1944, the Supreme Court upheld Korematsu’s conviction by a 6-3 vote.

One dissenting justice called Roosevelt’s order “legalization of racism,” but the majority ruled that the detention was a “military necessity’’ and not based on race. One justice who supported Roosevelt’s authority wrote that “the court could not reject the finding of the military authorities that it was impossible to bring about an immediate segregation of the disloyal from the loyal.”

After internment ended, Korematsu returned to the Oakland area where he grew up, settling in San Leandro.

His legal case was reopened in the early 1980s, and his lawyers argued that the government suppressed or destroyed evidence from intelligence agencies that Japanese-Americans posed no military threat.

A federal judge overturned Korematsu’s conviction on Nov. 10, 1983.

President Bill Clinton awarded Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1998.

And in 2010, five years after his death, California designated Jan. 30, his birthday, as Fred Korematsu Day.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.