Philly’s first harm-reduction coordinator takes new aim at city’s opioid crisis

Allison Herens, Philadelphia’s first harm-reduction coordinator, says the creation of her role signifies a changing perspective on addressing a drug crisis.

Listen 5:35

As part of its response to recommendations outlined by Mayor Jim Kenney’s special opioid task force last spring, Philadelphia has created a new position within the health department, a harm-reduction coordinator.

“Harm reduction” may be an unusual title for a public job in the United States because harm reduction itself — as a philosophy and a public health approach — has long butted against another approach to drugs. Unlike a “just say no” perspective, harm reduction essentially aims to reduce the risks associated with drug use instead of focusing on stopping it completely.

Allison Herens, who has stepped in as Philadelphia’s harm-reduction coordinator, said her title signifies a changing perspective when it comes to addressing a drug crisis that — by the end of this year — is expected to have resulted in more than 1,200 overdose deaths in Philadelphia alone.

Interview highlights

On what it means for the city to have a harm reduction coordinator:

I think it absolutely signifies a shift. I think it signifies as a city we are finally starting to, at least, address the fact that you can’t force people into treatment. We can have this moral code, but people still have their own choices in life, and part of helping people is really respecting and acknowledging those choices. As a city, if we really want to address the issue in a way that’s actually going to help people in the long run, we can put all these people into treatment. That’s not necessarily going to help if they don’t want it.

So we need to meet people where they’re at, if we really want to have a widespread impact on this issue, because it’s really not just about fatal overdoses. There’s a million other factors that go into this: the spread of infectious diseases, HIV, hep C, there’s a lot to tackle with this issue.

How do we keep people safe? How do we keep our community safe? We really don’t want to lose any more people to this crisis. The drugs that we see on the street are just incredibly dangerous, incredibly potent, we want to make sure we’re being vigilant in terms of safety.

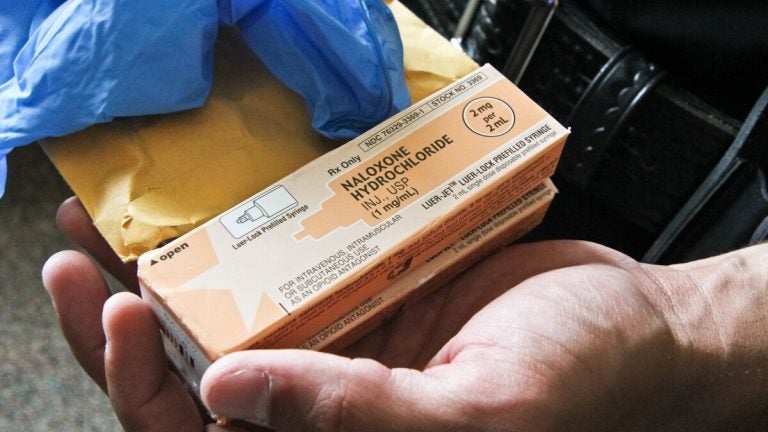

On amping up education and distribution of naloxone, the overdose-reversing drug:

I’m just trying to think about potential organizations and certain first responders who could be first responders, essentially populations that we haven’t targeted yet that could be exposed and could witness an overdose. And then [I’m] trying to think about how do we reach those organizations to make sure people across the city are prepared? I’ve recently worked with the office of homeless services a little bit to train their staff. I trained some of the district attorney’s victim advocates. I’m planning to schedule trainings with sheriff’s departments, and, potentially, the defender association.

It’s my opinion if you feel comfortable carrying [naloxone] and administering it, you should be carrying it. I realize there’s an access issue, it’s not that easy to get. There is a cost factor. Not everyone, especially active drug users, necessarily have insurance. It is covered through Medicaid completely … but if you have private insurance, the copay can vary.

Luckily, we have groups like Prevention Point who are able to provide the medication, and a large portion of our allocated naloxone from the department of public health goes to Prevention Point. And, in terms of getting it at the pharmacy at all, it’s a matter of whether they have it in stock, whether the pharmacist understands the standing order. So we’re also doing a lot from a department standpoint trying to educate pharmacists, trying to ensure they’re carrying it.

I’m hoping through my trainings to try to address some of those issues and get feedback from participants around whether they tried to get it after the training and what barriers did that come into, because I do want to try to decrease those barriers.

On why she does what she does:

The opioid crisis has had a huge impact on my life, personally, between family members and friends. I’ve always had a strong inclination to work with people in addiction. I previously came from more of a criminal justice reform and criminal re-entry background, but obviously there’s a ton of overlap between that and drug addiction.

When I originally went into social work, I wanted to work in direct service, initially, just to be able to inform larger policy. And it’s my big belief that if you don’t work with the populations that you’re trying to create programs and policies for, you’re not really informed about what they really need.

On the city considering a supervised safe injection site:

Here in Philadelphia, we are exploring the idea of safe injection. We are calling them comprehensive user engagement sites. I think, in particular, the name addresses that these sites are meant to be more than some place that people can go use. A lot of drug addiction stems from and has a lot of isolation associated with it. These sites could be places to work with those individuals and work with them around other issues that aren’t necessarily their drug addiction.

And through working with them in those other areas, it’s possible — and it’s been shown — those individuals are more likely to enter treatment. The site in Vancouver has detox and transitional housing in it. I don’t know if that’s something Philadelphia would also do, but it’s a great model to have.

I personally think that this is an initiative that will help save lives. It’s a medical intervention. It keeps people safe while they’re in their active addiction and until they’re ready to go to treatment, but this is not meant to be an end all be all. There are all the other initiatives we’re working on.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.