How to address New York City building emissions? One option: Start with steam

The inefficiencies of steam have gone unchecked for years. But now, that may change. Earlier this year, New York City passed a landmark law to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions

Listen 08:36

Snow falls on a street food vendor as he makes his way down Broadway with his cart past steam rising in New York, NY. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)

Growing up in an old New York City apartment building, Andrew Gladstone associated winter nights with a certain soundtrack. He lived on the Upper West Side in a skyscraper from the 1930s called The Opera, but the music he heard as he lay in bed was not exactly melodic.

It would start as a distant hiss, like a snake creeping through the walls, getting louder and louder. Then there would be a low bumping sound that evolved into a higher-pitched clanging, like someone banging on a metal pipe with a hammer.

“I would wake up from these pipes clanging, and it was like a storm of ‘BOM, BOM, BOM,’” Gladstone said.

The noise was only half of the problem. The radiators were on full blast, and his family didn’t have control over the temperature. They would open the windows, trying to figure out the optimal influx of cold winter air to offset the heat.

Gladstone’s story of violent sounds and infernal heat is not unique. These are the mundane facts of life when you live in an old New York City apartment building heated by steam. The practice of opening windows in the winter is widespread, and it points to a much larger problem in the city: These old heating systems are inefficient, they run on fossil fuels, and therefore they make up a significant portion of the city’s greenhouse-gas emissions.

The inefficiencies of steam have gone unchecked for years. But now, that may change. Earlier this year, New York City passed a landmark law to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions called Local Law 97. It specifically targets buildings, which are the source of 71% of emissions in the city.

The goal is to reduce building-based emissions 40% below a 2005 baseline by 2030. The task is monumental. Steam heat is everywhere in New York City. Any building in the city built before 1970 is likely to have it — and that’s most buildings. The architecture firm KPF found that nearly three-quarters of the buildings in Manhattan were built in just a few decades, between the 1900s and the 1930s.

Steam heat typically means there’s a boiler in the basement that burns oil or gas to heat water. The steam that results is sent up into the building through distribution pipes and fed into radiators in individual apartments. For the most part, the pipes and radiators installed when all these buildings were going up are still there. All that has periodically been changed out are the boilers.

It’s possible to make steam heat systems more efficient. The history of steam heat in New York City offers clues about why these systems are so broken today, and how building owners may be able to tackle their inefficiencies. Much of that history was uncovered by Dan Holohan, who dedicated his life to studying the topic. He wrote a book, “The Lost Art of Steam Heating.”

To Holohan, the history of home heating is a gripping story of survival.

“Winter was almost like a character in a novel, you know, it was personified in my mind. It would come indoors and try to steal your kids,” he said. “I looked at that, and I just got more and more interested in, OK, how did all this get going?”

When he first started looking into steam heat in the 1970s, he realized that the people who designed these systems in New York were dead. He took to the library, where he immersed himself in old engineering textbooks and boiler manuals and trade magazines. In one of the textbooks, he stumbled on a section that explains so much about why steam heating systems have problems today. It was a bizarre specification: A boiler had to be sized for the coldest day of the year with the wind blowing and the windows opened.

At the time, it was actually standard to install boilers that were big enough for people to open their windows in the dead of winter and still be warm. When Holohan dug a little deeper, he started to figure out why.

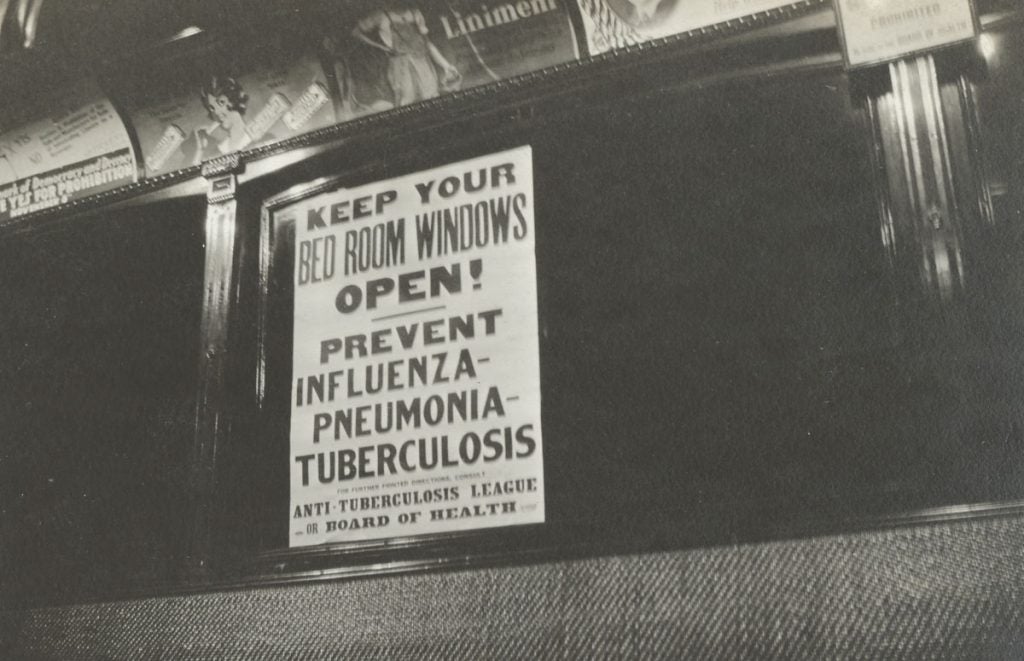

The 19th century was not a good era for public health in American cities. “You’re looking at people just living in horrible conditions,” he said. Families were packed into cramped apartments with poor ventilation and unsanitary facilities, where airborne diseases such as tuberculosis spread easily.

At the turn of the 20th century, as germ theory entered the public consciousness, fresh air came to be seen as one of the best ways to prevent the spread of disease. In 1901, fresh air was written into the building code through the New York State Tenement House Act, which mandated that every room have a window facing the outside. Along with more windows came medical advice: keep the windows open. This excerpt from a 1908 speech by a doctor, titled, “Treatment of Incipient Tuberculosis,” offers a glimpse into the mindset of the times:

“Open air or fresh air is essentially necessary under all conditions; let every breath or inhalation have no suspicion of ever having been breathed before … The only way to be sure air is pure and fresh is to feel it blowing across your face day and night. Sit or sleep in a gentle current of air all the time you are indoors.”

Holohan concluded that this fixation on the curative power of fresh air influenced the size of the boilers and the number of radiators that were installed when most of New York City was being built.

In addition to the open-window rule, another historical factor fed into the problems with steam heating systems today. Throughout the 20th century, the fuel source for steam heat kept changing.

Originally, Holohan said, the systems were designed to run on coal. In the 1930s, many buildings switched over to oil-burning boilers, followed by natural gas in the 1970s. He said with each new fuel source, there was a lack of guidance on how to size the boiler. Whoever was replacing it would often look at the previous boiler and then increase the heat capacity by 10% to 20% to make sure residents wouldn’t be cold. Over time the boilers became increasingly robust. Today, when it comes time to replace a boiler, contractors will typically put in the exact same size that was there before.

Holohan’s examples suggest that, to improve efficiency, the first thing a building owner should look into is downsizing the boiler. Today, engineers have developed better methods for measuring correct boiler size based on the rest of the system.

But boiler size isn’t the only problem. The new fuel sources also changed the way the boiler functioned, according to Sean Brennan of the nonprofit Urban Green Council. Coal burned slowly and consistently throughout the day. Oil and gas burn very quickly, sending steam rushing up through the pipes. That heats buildings more quickly than coal did, so the oil and gas boilers are designed to cycle on and off, either manually or automatically. This cycling wastes energy, and makes the pressure in the system unstable.

Earlier this year, Urban Green Council released a report called “Demystifying Steam” that offers a whole menu of recommendations for improving the efficiency and function of steam systems. These include smaller boilers, valves that regulate how much steam enters the radiators, vents that make sure trapped air can escape, sensors that measure indoor temperatures, and modulating burners that allow the boiler to vary the heat output rather than just turning on or off. Taken all together, the changes can reduce a building’s fuel use by 20%.

Brennan said the changes would cost less than a dollar per square foot for an average multifamily building. “Typically, these buildings are spending between 50 cents and $1.50 per square foot to heat the building annually anyway. So we’re not talking about a huge expense,” he said.

For a medium-size building, that might be somewhere between $75,000 to $100,000. Brennan estimated that upgrading steam systems across all residential buildings in the city would cost $2 billion.

One obstacle, according to Brennan, is the low cost of natural gas. Since gas is so cheap, there’s not much incentive to fix inefficient systems. Another is that many New York City residents don’t even see their heating bills. They just pay a monthly maintenance fee — the gas bill isn’t broken out.

“While they’re very dissatisfied with their heat, they don’t necessarily correlate that with a willingness to invest or pay a premium to get these problems fixed, which is at the crux of this problem,” said Brennan. “They’d much rather just open their windows.”

But when the penalties for the building emissions law go into effect in 2024, that could change. The law sets emissions caps for buildings over 25,000 square feet — that’s about 50,000 buildings. The owners of those buildings will be fined $268 per metric ton of greenhouse gas they emit over the set limit. About a quarter of the buildings are already compliant with the law. But the remaining 75% will need to address their steam heat problems by 2030 to avoid penalties.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s long-term goal is for the city to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. That means people may eventually have to get rid of steam heat altogether. That’s a very different proposition than improving efficiency. It would be a major disruption — just imagine all the pipes and radiators being ripped out of thousands of buildings. Families would have to temporarily move out of entire wings or floors.

More than 80% of New York City buildings are heated by steam. To Brennan, that number is daunting, but it also represents a huge opportunity to reduce emissions. He said there is momentum growing around making these changes, and that if we want to avoid the worst effects of climate change, we can’t ignore steam heat anymore.

“People are used to investing in [buildings], and we know they’re going to be here. So let’s make the investment now,” he said.

Whether that momentum has touched the typical apartment-dweller remains to be seen. Cate Flanagan grew up in a New York City apartment built in 1901, and her experience mirrored Gladstone’s. She recently asked her dad, a lifelong New Yorker, if there had been any talk in the building about upgrading the heating system, and his response: “Steam now, and steam forever.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.