New procedure leads to miraculous recoveries in stroke patients

Listen 8:09

The Hinrichs family, photographed almost a year after Kurt's stroke. (Courtesy of Kurt Hinrichs)

On July 17, 2014 Kurt Hinrichs, of Gladstone, Missouri, went to bed early. When his wife joined him, she woke him with her snoring. That often happened.

“Usually, when I wake up, I grab my glasses and I walk into the living room and I lay back down on the couch and go back to sleep. That particular night, I tried to get out of bed, and I crashed,” Kurt said.

This, in turn, woke his wife, Alice.

“At first it was like what’s going on,” Alice said. “Are you dreaming? Are you sleepwalking?”

“And I am thinking this is a nightmare,” said Kurt.

He wasn’t responding to anything Alice asked him. Finally, she grabbed his face between her hands and tried to make him look in her eyes. She told him if he didn’t respond, she would call 911. “And there was no change, nothing at all,” Alice said.

By the time the paramedics arrived, just minutes later, Kurt wasn’t speaking and his entire right side was paralyzed. They recognized that Kurt was having a stroke.

“When they wheeled Kurt out of the house was the hardest part for me because it was like I knew at that point and time that he was not going to come back home through that door,” Alice said. “If he was home, I knew he would be bedridden or in a wheelchair. I really didn’t have a lot of hope that my husband would be normal again. Ever.”

Kurt, speeding towards St. Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, had his own reckoning. “That’s when I realized that this was not a nightmare, that this was the truth, that I was awake but there was something major and massively wrong with me.”

New treatment

About 800,000 people suffer strokes every year in the U.S. Most of them are caused by a clot blocking a vessel, which cuts off pathways for blood to get to the brain.

“Whatever region of the brain is affected, the part of the body that controls will basically cease to work properly. You may become paralyzed on one side of the body, you may have the inability to speak or understand, you may lose vision,” said Brett Cucchiara, a stroke neurologist at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

If the vessels don’t reopen, brain cells start to die. Stroke is the number five cause of death in the country.

And though doctors have known about strokes for a long time, it wasn’t until relatively recently that doctors could do anything to help patients in the midst of a stroke. In 1996, something called tPA came on the market – it’s a chemical clot busting medicine that can break up masses. But tPA works for just a minority of patients.

Now, another new advance lets doctors treat massive strokes.

Lazarus patient

At St. Luke’s Hospital, doctors got Kurt on tPA, the clot busting medicine, but the chemicals weren’t working. That’s when nurses approached Alice and asked if the doctors could perform a new kind of mechanical procedure on her husband. She’d never heard of it – it’s called a mechanical thrombectomy – but she agreed

“They got me on the table. And the last thing that I remembered was a huge bank of screens coming over me and I’m thinking what is that for,” Kurt recalled. “And I was out.”

Over the next 20 minutes, doctors inserted a catheter into his femoral artery, in the groin. They wove the catheter up into the aorta, the main artery in the body, then into a carotid artery, which takes blood into the head and neck, and finally into the brain vessel where the clot was located. “Once it gets into the brain, that’s where it becomes a little trickier because the arteries make a lot of sharp turns and curves and do become very small and somewhat delicate,” Cucchiara said.

Those huge banks of screens helped doctors see where they were going as they steered the catheter towards the clot. Inside the catheter was a small piece of equipment that would be used to extract the clot.

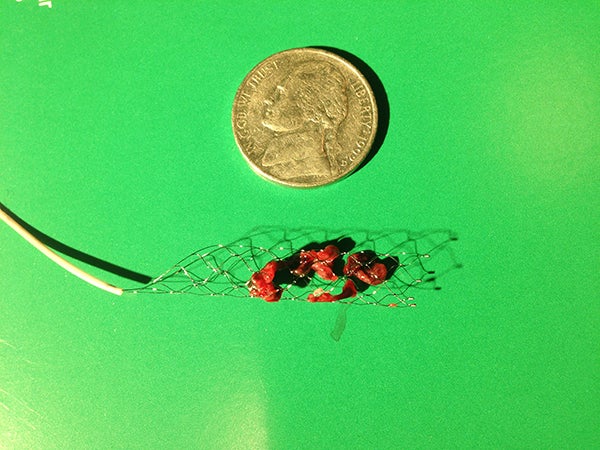

Cucchiara showed one of these devices to me in his office. It looked like a very thin little fishing net on the end of a metal wire. The net is deployed into the clot and traps the mass.

Once the mass is in there, the little net, with clot in tow, is pulled back into the catheter and the whole thing is pulled out of the body.

“Somewhat analogous to like a plumber who comes and uses the plumbing snake to pull a clog out of your drain,” Cucciara said.

Recovery

If the intervention is successful, blood flow is immediately restored to the brain.

“Many times within 10 or 15 minutes of that happening the paralysis will melt away, their ability to speak will completely return, so it can be quite a remarkable, almost miraculous recovery that you can see right in front of you,” Cucchiara said.

After Kurt Hinrichs’ procedure, he was able to start wiggling his right arm and leg. His speech returned soon after.

His wife, Alice, had gone home to tell their three children about what had happened. When she returned to the hospital about four hours later, Kurt looked at her standing in the doorway to his room and about as clearly as he spoke before the stroke, asked her, “How is your morning?”

“And I just kind of stopped and looked behind me and I looked at him,” Alice said. “My gosh. It was absolutely amazing.”

Kurt is what doctors sometimes call a Lazarus patient. A massive stroke like the one he suffered can kill patients, or leave them paralyzed and non-communicative. But after the intervention, he walked out of the hospital without any serious, lasting effects.

Looking ahead

In 2015, after several studies demonstrated how effective mechanical thrombectomy is for certain stroke patients, new guidelines made it standard of care. But Guillermo Linares, Director of Neurointerventional services at Temple University Hospital, said not all patients who could benefit are getting it, yet. Figuring out how to mastermind the systems to coordinate such care is even harder than fishing a clot out of a brain. “The delivery of the therapy in hospitals I think is relatively easy when you compare it to what is needed in society at large in order for this therapy to be available,” Linares said.

Both the clot busting medication and mechanical thrombectomy are a race against time. They have to be administered very quickly, within hours of symptoms.

Linares said many pieces have to fall into place simultaneously. “So when a patient becomes symptomatic there has to be a very low threshold for calling emergency medical services. And the ambulance has to arrive quickly. The stroke has to be identified, the patient has to be brought to a stroke center.” And on and on. The coordination has to happen within a hospital, but perhaps even more importantly, it has to happen among hospitals and medical service providers.

Not all hospitals can perform this procedure. In rural areas especially, which often lack hospitals with the resources to do a mechanical thrombectomy, medical teams have to figure out what to do with stroke patients.

“As soon as emergency medical services get to you, should they drive you to the closest possible hospital, or should they drive past a smaller hospital in order to get you to a larger comprehensive stroke center where more options may be available?” Linares said. “Well there’s risks and benefits to either path.”

Some cities have put out guidelines directing paramedics to follow one path or another. Others are tweaking existing protocols and in the process of writing and testing new rules. But figuring out a clear, organized method to get patients help quickly will be one of the next big advances in stroke care. Linares said healthcare providers have previously developed systems for other major issues, like heart attacks.

“That is exactly what we’re trying to do right now is to organize ourselves so that time, which we know is brain — time is brain — we can do this and we can do it really quickly for the people that need it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.