It’s a rollercoaster raising a transgender child in the spotlight

Listen

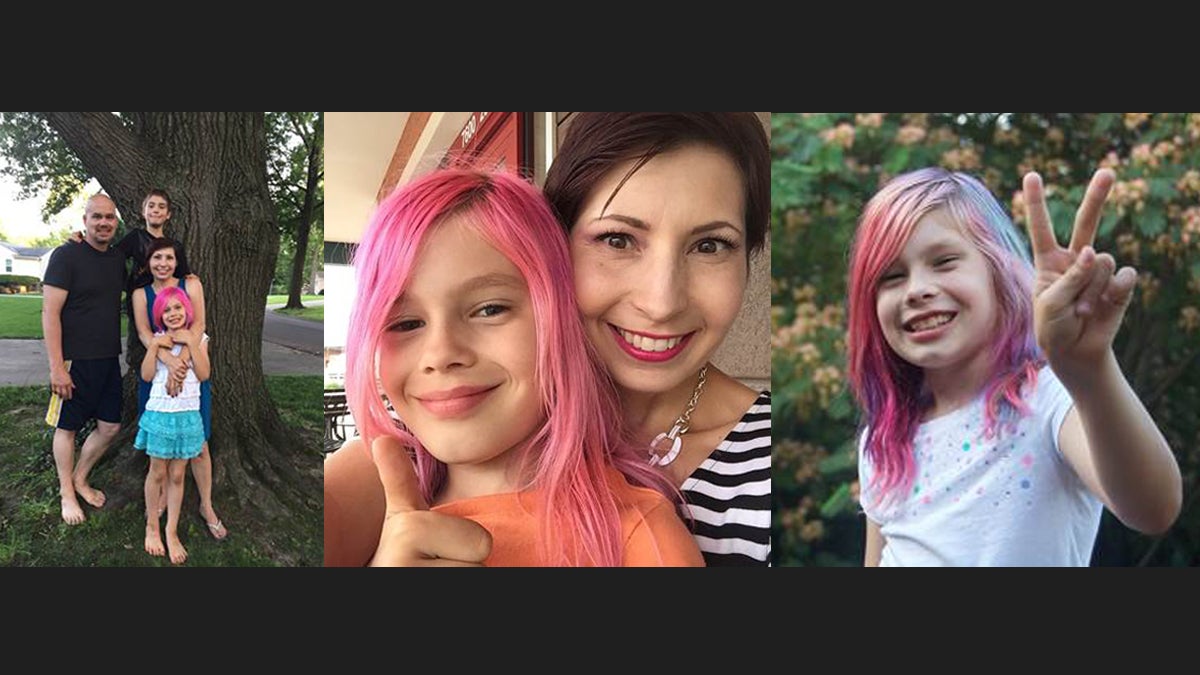

The Jackson family has been balancing public and private life after Avery Jackson, 9, was featured on the cover of National Geographic. (Courtesy of Debi Jackson)

In Kansas City, the Jackson family is learning to live with the costs of a more public life.

At age 3, the child Debi and Tom Jackson knew as their youngest son began wanting to wear sparkly shoes and to shop for clothes only in the girls department. And around age 4, when their preschooler became sullen and stopped smiling, Debi knew they had to do something.

“And then she got to the point where she directly told us, you know, ‘You think I’m a boy, but I’m a girl inside,'” Debi said.

She thought it might help other families if they heard from her little girl, whose name is now Avery. In 2015, Avery and her mom posted a YouTube video in which Avery tells the early story of her transition.

“Even though I was a girl, I was afraid to tell my mom and dad, because I thought they would not love me anymore and they would throw me out and stop giving me any food or anything,” Avery says in the video.

Back then, Debi and Tom shared their own struggles and trimuphs but didn’t want me to interview their daughter. This year, they invited me over to the house to meet her.

The Jacksons homeschool Avery and her brother, Ansen, who’s 10. The two spend lots of time at side-by-side computers in a big room off the kitchen where they study and play video games.

With pink, blue, and purple hair tumbling down her back, Avery is like many 9-year-olds who have an annoying big brother.

“Don’t hit me,” she whined as Ansen jabbed his arm into her shoulder.

Avery is tired of being asked about what makes her different, and the day I visited she let me know.

“Don’t ask me these questions,” she said. “I’m just playing a game.”

But since Avery’s mom said it was OK, I pushed a little bit, promising not to go on for too long. Avery was still annoyed.

“The thing is, my mom told me you were just gonna come and say ‘Hi’ and talk to her,” Avery said. “And this is the thing they always do. I’m the one that always gets the question. I’m not interesting! I’m just a boring person that sits at a computer animating and making games all day. That’s really all I ever do.”

Avery and her family were out front early with their experience. But that visibility has cost them.

The Jacksons say they were kicked out of their conservative Christian church. They lost friends and family. Tom’s a chiropractor. He says he’s lost almost half of his patients.

Recently on the podcast “How to be a Girl,” a reporter asked Debi if she’d want to go back in time.

“There’s a small percentage of me that says, yes, absolutely, in a heartbeat, take it all away,” she says on the podcast. “I wish people didn’t know our names. I wish people had never heard of us. I wish we just could go about our daily lives and not have to think about these things.”

The balancing act of public and private life has gotten even more complicated in recent months.

In January, Avery appeared defiant and proud on the cover of National Geographic magazine for a special issue about gender. And soon after, there were more requests for interviews and pictures.

Sometimes that’s fine. Avery wants to be a pioneer and role model. She has her own website, and she wrote a children’s book called “It’s Okay to Sparkle.” But her mom says there are other times when Avery just wants to fit in, to be anonymous.

“In her brain, everyone’s going to be calling her ‘That transgender girl from National Geographic,'” Debi said.

At times the attention is frightening, Tom says.

The Jacksons say, especially since the November election, they’ve gotten death threats and messages from white supremacists.

Critics have said the Jacksons shouldn’t be allowed to raise children.

“When we’re out in public, I literally look 10 feet in every direction,” Tom said.

“And we’ve been out in public before where someone will walk up to us and say, ‘I know who you are.’ And then you have that moment of panic and fear, and they’re like: ‘I absolutely love you guys, you’re great.'”

Tom and his family are learning to live with the costs of their more public lives.

Experts point out there can also be costs for people who choose not to transition, although they feel they are living as the wrong gender. The distress some people experience when they don’t identify with the gender they were assigned at birth is called gender dysphoria.

Heather McQueen, a former social worker with the Gender Pathways Clinic at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Missouri, counsels children and their families.

She tells parents to look for red flags.

“My child has been extremely depressed for the last six months. My child has been wearing three sports bras, can barely breath because they’re trying to conceal that they have breasts,” McQueen said, by way o f example. “So that is a concern.”

Here’s a haunting statistic: Some 40 percent of people with gender dysphoria will attempt suicide according to a number of studies.

This has motivated Debi Jackson to step up her public appearances. She recently was the keynote speaker at a packed Planned Parenthood conference in Kansas City, Missouri.

The event highlighted health care gaps for LGBTQ communities, how to educate providers, and why violence against transgender people is so high.

Carmen Xavier spoke at the conference and talked about transitioning late in life.

“The fact that I’m in my 60s, there’s also a sense of urgency here,” she said. “It’s now or never.”

Xavier had been a popular elected official and prominent community activist. Living her true identity as a woman has isolated her from professional colleagues, even family. She’s lost status and friends.

It’s clear talking to Xavier, she still struggles. But seeing 9-year-old Avery Jackson, out there being herself, inspires her.

“And isn’t it good that the child is becoming bored and irritated by all the attention?” Xavier said. “She just wants to be her.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.