Huge jury awards often pared before going to compensate victims of Philly police abuse

City officials are concerned because, nearly every year, Philadelphia taxpayers are on the hook for about $10 million total to settle claims of police abuse and misconduct.

Listen 5:13

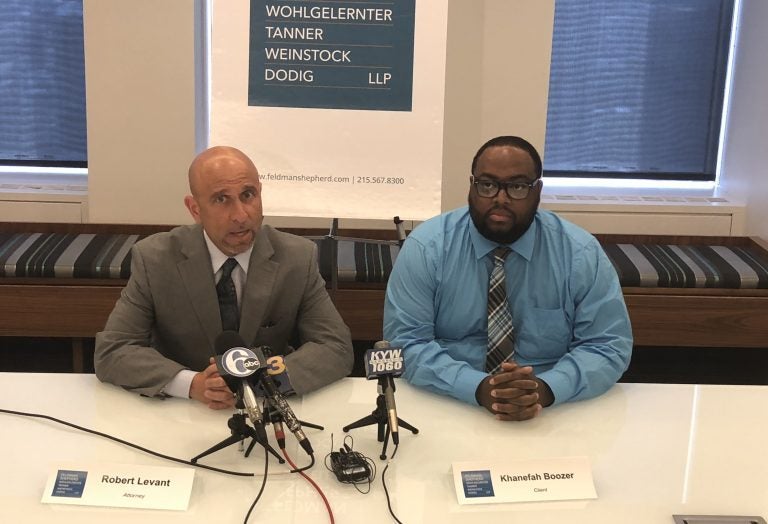

Attorney Robert Levant (left) with his client Khanefah Boozer. “He has been injured in ways that most of us can’t ever fathom," said Levant of Boozer. "It’s truly everyone’s worst nightmare to have this happen to them.” (Bobby Allyn/WHYY)

Khanefah Boozer of Northeast Philadelphia spent three years and eight months imprisoned awaiting trial on charges that he fired shots at a police officer. In the absence of ballistic evidence or additional witnesses to support the police officer’s story, a jury acquitted him. While Boozer was incarcerated, his mother and sister died.

“Really, for the rest of his life, he’ll have to wonder whether his mother really knew he was innocent,” said lawyer Bob Levant, who represented Boozer. “What it was like for her in her dying days to not have him there.”

Levant filed a civil lawsuit against the police officer, Ryan Waltman, and the jury found that Boozer should get $5 million to compensate for his pain and suffering — and another $5 million to send the message that his incarceration was unjust.

“When you see a $10 million verdict, it does cause some concern,” said Craig Straw, first deputy city solicitor of the Philadelphia Law Department.

City officials are concerned because, nearly every year, Philadelphia taxpayers are on the hook for about $10 million total to settle claims of police abuse and misconduct. So this sole jury verdict would double what officials typically pay out over allegations of misbehaving police.

City lawyers, who are appealing the historic verdict, have a track record of successfully scaling back large jury verdicts following an appeal.

Big awards get small

In 2006, a jury awarded a man $5 million; after appeal, the city settled for $500,000. In 2008, a $10 million jury verdict was knocked back to $1.1 million after appeal. And, in 2016, a $1 million verdict over police abuse was completely reversed when the city fought it.

“The city of Philadelphia has been fortunate that large verdicts have often been reduced after an appeals court has looked at them,” Straw said.

Multimillion-dollar jury verdicts cause screaming headlines. But the awards rarely survive the appeals process.

Paul Hetznecker and other civil rights lawyers say such reversals insult the victims of police abuse.

“When the jury levels a huge award against a particular defendant police officer, then that should be recognized as the measure of injustice and the compensation for that injustice,” Hetznecker said.

Compensation and punishment

When jurors in the Boozer case were deliberating on what to award to him, they had two categories: compensatory damages and punitive damages. Jurors wrote $5 million for each.

Compensatory damages are a way to make up for something bad that’s happened.

“Those damages really represent the emotional toll it takes on a person to be wrongfully incarcerated, the humiliation they face, the torment and turmoil,” Levant said.

The punitive damages, meanwhile, are intended to deter future misbehavior, a way to send a message.

“The essence of punitive damages is to try to make this be the very last time that the false testimony of a police officer puts someone in jail when they were innocent,” Levant said.

Here is where things get complicated. Under state law, Philadelphia and other municipalities do not have to pay punitive damages. And in Boozer’s case, if the award makes it through the appeal, city officials say they have no intention of paying the punitive damages. Waltman, the officer, is not independently wealthy. So then, how will that $5 million ever get paid?

“I’ve always been cautious what happens when you reach the point when you have a really big verdict against an individual officer and the city says, ‘Forget it, we’re not paying,’ ” said Alan Yatvin, a longtime plaintiff’s lawyer. “This is an ongoing tension of what is the responsibility of the city when there may be a verdict that the city is not going to pay.”

In most civil cases against the city, the payout is legally capped at $500,000. But, since the suit brought against Waltman included claims of malicious prosecution, it’s known as an “intentional tort,” and therefore there is no limit on the amount juries can award.

‘Willful misconduct’

Waltman as an individual, not the city of Philadelphia, was named as a defendant in the civil suit. And as policy, city lawyers defend municipal employees — including officers — in civil lawsuits, as long as the conduct that initiated the suit was not considered “willful misconduct.”

But who exactly determines that is an open question in Pennsylvania. In fact, a case pending before the state’s high court focuses on whether a jury, or a judge, should decide if an alleged act should be considered “willful misconduct.” It is a critical issue and potentially germane to the Boozer case; if an incident falls within that category, it theoretically is no longer the city’s problem.

“In state court, in order to win against an officer, to get past their immunity, you have to show willful misconduct, but once you do that, it’s a Catch-22, because then the city doesn’t have to represent the officer,” Yatvin said.

Historically, in cases of an officer’s willful misconduct, the city has paid jury verdicts under an agreement with the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 5, the union that represents officers. A request for comment from members of the FOP was never returned.

In the Boozer case, city lawyers are planning to seek a new trial partially on the grounds that the willful misconduct question was never answered, arguing that the case ended in an incomplete verdict.

Often, according to legal experts, the larger the jury award, the more carefully appeals courts review them, meaning the end of the case could be many years away — that is, if the parties do not decide to settle for another amount before the appeal concludes.

Meantime, Levant said Boozer was imprisoned for nearly four years as an innocent man, deserves money, and a jury agreed. The $10 million represented justice to the panel. The jury verdict, he said, should stick.

“I hope, at some point in time, the city stops and looks at the case and wants to do the right thing by Mr. Boozer,” Levant said. “He has been injured in ways that most of us can’t ever fathom. It’s truly everyone’s worst nightmare to have this happen to them.”

On the other hand, the city contends, the taxpayer funds that could fulfill the jury’s verdict might be better spent on other city needs such as fixing roads and improving schools.

“If there’s a legal reason why the city shouldn’t be paying something, I think it’s our obligation to take that on and potentially preserve the taxpayer money for other causes.” Straw said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.